License to Grow

A planter of herbs is a virtually skill-free endeavor.

Growing herbs has always seemed to me one of those activities best practiced by the newly enthusiastic—the college student who has made the leap from dorm to apartment, or the young couple who finally gives in to suburbia. Is there a better symbol for starting fresh than a window planter that quickly becomes abundant with edible verdancy? Though real cooking happens everyday in our house, I’ve always just bought whatever fresh herbs I have needed along with the other ingredients. I think this had more to do with convenience than cynicism.

Two years ago I was given a pot of English thyme. I was going to clip the whole bunch of tender shoots and use them that night on a roast chicken, but for one reason or another it was forgotten. A few days later, out of pity or curiosity, I planted it alongside some Coleus and Celosia. I was amazed to find it had almost doubled in size by the end of the week, and by the end of the following I was clipping strands to thin the growth and using the fragrant leaves wherever I could. The realization for me wasn’t that herbs are good—I have been adamant about including fresh ones in most of what I cook for years. The abundance was the revelation.

The following year, alongside thyme, I planted basil, rosemary, tarragon and parsley. They flourished like weeds. Which taught me my first lesson about herbs: they do not require any skill to cultivate. They want to spread and thicken, especially basil and parsley, which very quickly dominate a planter, sometimes to the detriment of less vigorous herbs. If you have ground, put those there, saving planter space for thyme, tarragon and rosemary where they will receive unobstructed air and light.

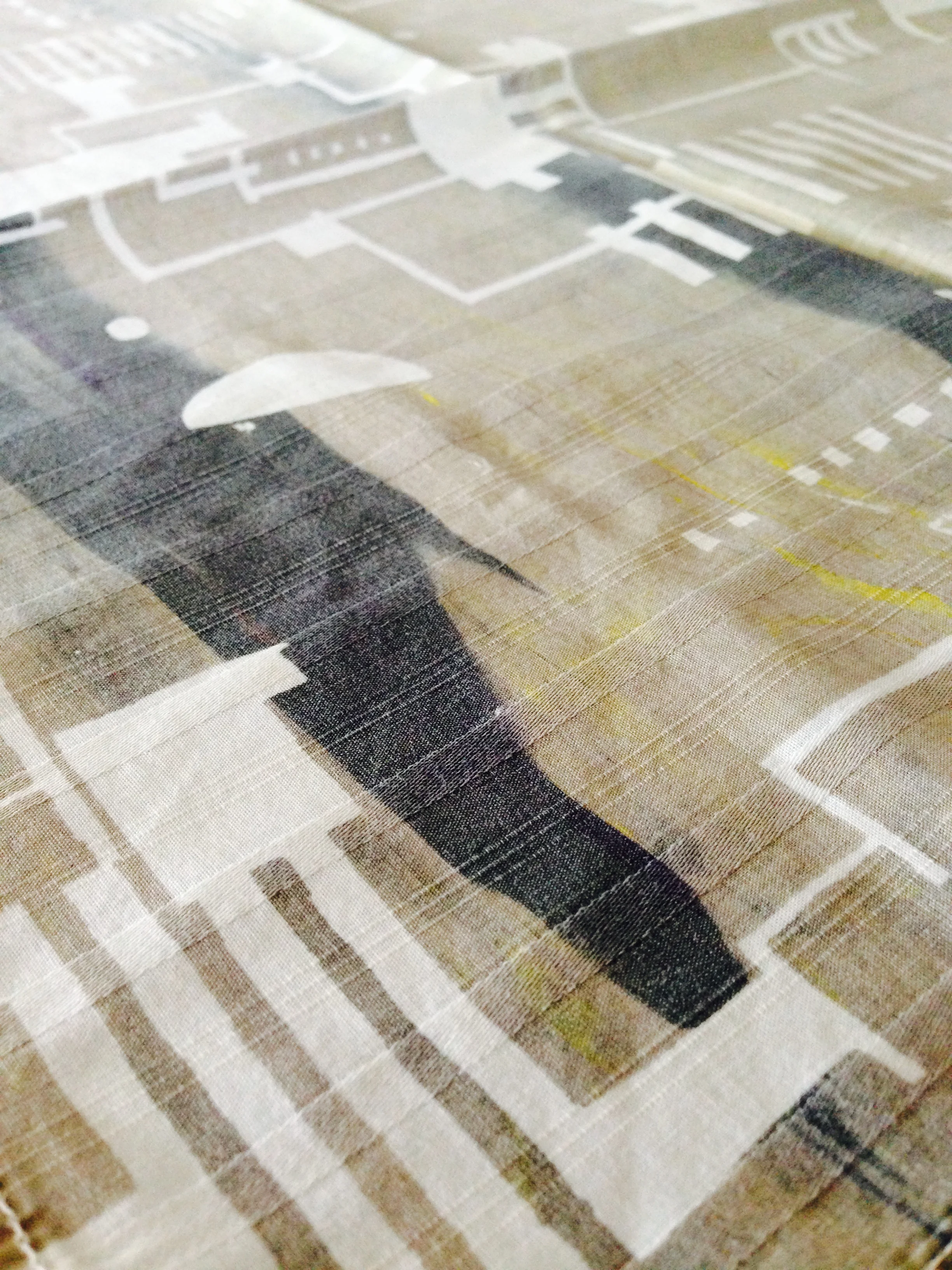

Pesto with body.

The only maintenance needed (other than water) is thinning—a regular harvesting which is the sole reason for planting herbs anyway. Woody herbs, like thyme and rosemary, will need a pair of snips; basil, parsley and tarragon are tender enough to pluck with fingertips—just be sure not to disturb the root structure. I like to take a combination of new growth, which is usually found at the top, and inner, older growth from the center or the interior. This practice is not just for the health of the plant; the combination of tender, new herbs and more mature ones provides the full range of flavor in a dish.

All this abundance requires recipes that star herbs rather than calling for them as a mere seasoning. A salad of herbs and something more neutral, like butter lettuce, can be a very refreshing start to a meal. Tarragon and parsley are the main ingredients in Green Goddess Dressing—that 1920’s classic. And packing herbs onto a piece of meat before roasting is rarely a miss. But if the herbiest punch is desired, little approaches pesto. To make a good one, strike the gloppy, buffet horrors and mix-and-match noodle/sauce restaurants from your memory, focusing instead on the name itself. Pesto is derived from the italian verb to pound or crush, inspired by the original mortar and pestle method. From Provence to Genoa preparations call for various herbs, nuts, cheeses and oils—not out of wild experimentation, but based upon availability, that most crucial of ingredients.

Basil Pesto

Wash a few handfuls of freshly plucked basil. Dry. Toast a small handful of pine nuts or walnuts in a dry pan. Let cool. With a vegetable peeler, fill a small ramekin with strips of a hard cheese, like Pecorino or Grana Padana. Place nuts and basil in mortar and grind in circular motion until a fairly uniform paste is achieved. Grate in a pinch of fresh garlic. Slowly incorporate extra virgin olive oil, about half a cup total, mixing continuously with pestle. Grind in cheese.