The Building Blocks of Fitness

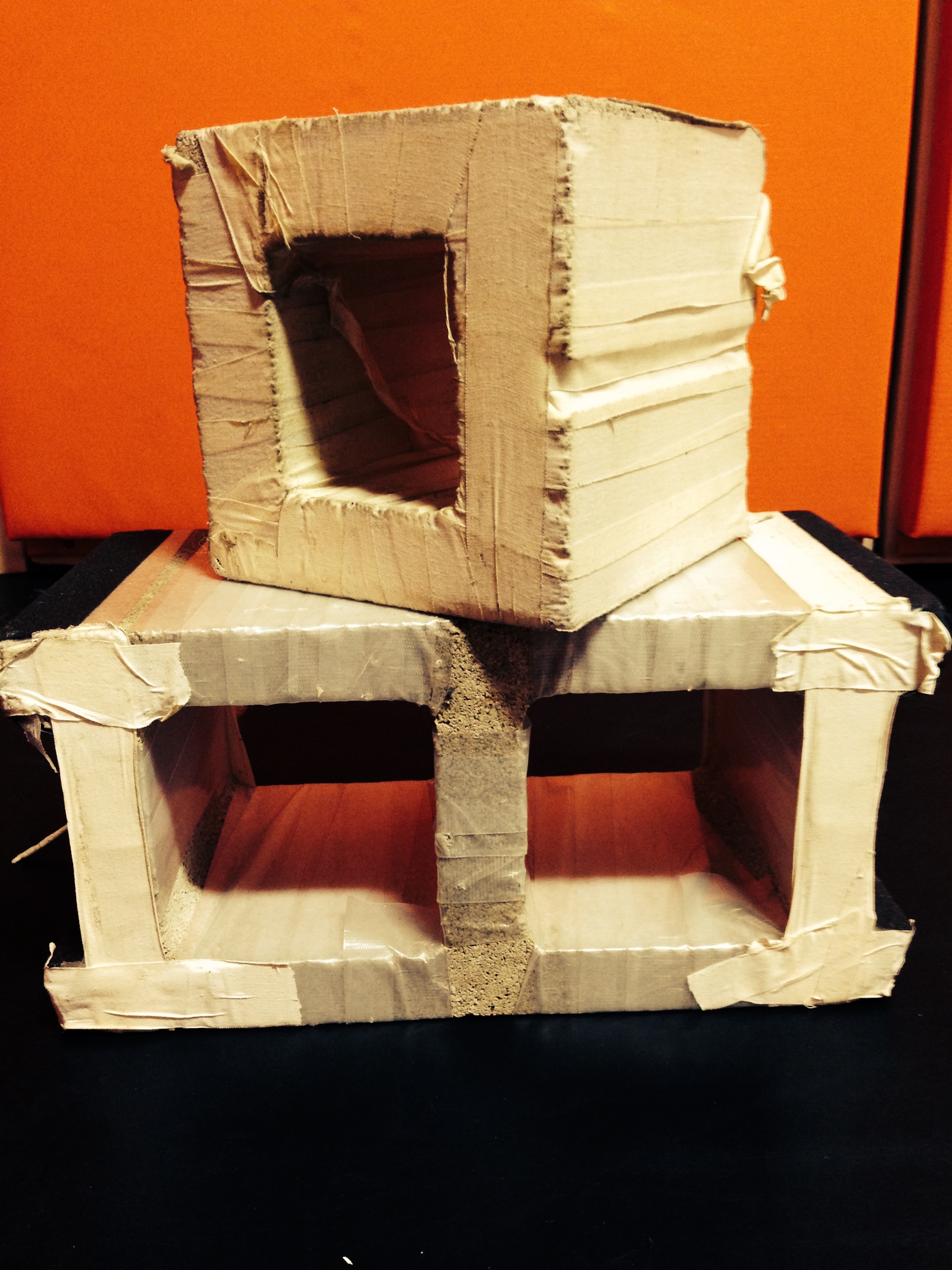

The standard block below; an 18-pounder on top. Both are taped to preserve your manicure.

For two summers during high school I worked a construction job for a family friend. My older brother had done the same, and while I wouldn’t say it was a right of passage, choosing instead an internship (as current high schoolers seem to prefer) might have been regretted. The second year, after my job had ended and before heading off to college, I visited some friends in the South of France. I arrived with calluses, a badly blackened thumbnail, and, I am not ashamed to admit, muscles. Not the grotesque, rippling sort popular today, just the burnished leanness one acquires from proper labor.

As I’ve mentioned in the past, I have a firmly rooted distrust of fitness gadgets. If pressed, I can make a few concessions though. One would be a ledge of some description or, better still, a sturdy tree branch. Pulling oneself up, like pushing oneself up, engages complex muscle groups and is efficient and portable. Besides the floor (for push-ups) and branches (for pull-ups) I can recommend another excellent fitness tool: the cinder block.

In the last few years a vogue has developed for fitness regimes involving all manner of junk--chains, tires, rock-filled duffle bags. The idea--a good one, I think--is to motivate the user who may have fallen into a rut by introducing unconventional routines and objects. In basic terms, one looks and feels impressive doing pushups with heavy-gauge chains wrapped about the torso. Of course it seems silly to pay a club or a trainer to gain access to these things. A better approach is to identify a poorly guarded construction site and pilfer a cinder block.

Cinder blocks exist in various shapes and sizes, but the standard is the 8X8X16, which is the iconic double-chambered block one thinks of when asked to picture one. This type of block has a number of advantages beyond its wide availability though. It is around 30 pounds, give or take, which, for the average male, is an ideal weight to hoist about. The shape is important too; the central chambers and the ledges at the ends allow multiple ways of grasping the block. The material itself--coal ashes mixed with cement--provides excellent grip, even when wet. One might choose to file any burrs, or even tape the edges, but in its original state, the standard cinder block should be ready to use. You’ll notice no batteries, chargers, long-term contracts or unhinged personal trainers are necessary.

Perhaps the thread that ties these low-tech exercises I’m fond of together is their relationship to momentum. For years momentum was thought to be the very thing that should be eliminated from exercise, and this remains the case today for the bench press, the dead lift and a list of others. But momentum isn’t universally unwanted. The key is in understanding when momentum is making an exercise easier or dangerous (bad) and when it is providing the challenge (good). Effective exercises either resist or use momentum as a way of engaging many more muscles than the obvious ones, especially those in the torso. Done repeatedly a cardiovascular workout is inevitable; it’s simply impossible to execute repetitions of complex movements without raising the heart rate. One might consider shoveling snow or loading hay bales on to the back of a truck as examples.

But why exercise like this in the first place? Why hoist building materials when air conditioned gyms lined with pristine, neoprene-swathed equipment exist? To answer that we must briefly return to the South of France. The friends with whom I stayed that summer had access to hotels and beach clubs, each with sparkling gyms, and while I spent the majority of my time swimming, nightclubbing and eating, fear of losing the definition I had developed in the weeks prior compelled me to spend an hour each day exercising. I would curl and bench and squat and, worst of all, use an elliptical, which was considered tres chouette at the time. Perhaps it was the uncommonly good food, or the countless aperitifs, but despite all the effort I noticed I was losing, if only to my eyes, some of my brick-lugging physique. Actual labor, I now understand, requires serious expenditure over a period of time rather than the short bursts of energy used to create beach muscles, and short of securing work as a part-time laborer, exercising with a cinder block achieves the same efficiency and effectiveness. Portability is another matter.

For the skeptics, here are a few moves to try with your cinder block. Run through two dozen repetitions of each exercise and at least two circuits of the routine. Follow liberally with Pastis.

The Twelve-O’clock Block

With the block on the floor in front of you, form a stance over it allowing your feet to be more than shoulder width apart. Grip the block how you see fit--the most sensible way being lengthwise by the protruding ledges of each side. Starting with your legs (and with a straight back) lift the block, permitting momentum to assist your arms in carrying it up and over your head. Hold for a beat, and then return to starting position. The block should go from a 6 o’clock starting position to a 12 o’clock extended position and then back to the 6 o’clock. The movement should be explosive but smooth.

The Faux-Hay-Bale

Begin by grasping the block as above, this time permitting the block to hang from your fully extended arms somewhere by your pelvis. Feet should be shoulder-width apart. Lower the block to your right side, twisting and bending your torso as you do. Once the block is as low as your knees, power it back up in a diagonal sweep to your left above shoulder level. Imagine you are picking something heavy from low on your right and putting on a shelf high up to your left. Or loading hay bales. Do the same but to the other side.

The Semaphore Shuffle

Permit the block to hang from your fully extended arms in front, as above. Feet should be shoulder width apart with plenty of bend in the knee. Hoist the block up in front of you, arm extended as far as comfortable, and straight over your head. Slowly lower the block down behind your head by bending at the elbow. Return the block to the starting position by doing the above in reverse. Use the spring in your legs to help your arms, and tighten the abdominals to steady the movement. You should resemble a semaphore operator guiding an airliner from the runway. Do be careful not to scalp yourself on the approach.

For the truly dedicated. Max Steiner Design, Brooklyn.