Several years ago, in the intimate ballroom of Manhattan’s Carlyle Hotel, I stood and delivered a best’s man’s speech to the guests of my older brother’s wedding reception. It was a mixed crowd; a younger set expected the groom to be well roasted; the aristocratic forehead of the Bride’s father, prominent and frightening even from a distance, reminded me, however, that his friends filled a majority of the seats and they expected banal brevity lest the consommé cool.

I found my solution in my inbox. For the better part of the previous year my brother and I had exchanged dozens of emails concerning the commissioning of a dinner jacket for the occasion. This had not been an ordinary exchange. My brother is rather particular, and as even a casual reader here may gather, I too have my opinions. Among other preferences, my brother does not tolerate any cloth that even remotely itches. He wishes to be swathed in gossamer, and though I do not understand the compulsion, and tried mightily to sway him toward stouter stuff, it was his wedding, not mine.

And so what developed was a semi-technical exchange concerning microns and mohair, barathea and grosgrain, peaks and shawls--the sort of discussion to which anybody who doesn’t count themselves as a clothing enthusiast might raise an eyebrow. My brother’s illustrative written style made my job easy when it came time to deliver the speech; why tell jokes when direct quotations, delivered in a controlled deadpan, prove far funnier?

At the heart of this light-hearted moment though is a debate about cloth. The opposing camps could not be clearer: the majority seeks the finest, lightest and most ethereal cloths, whatever the cost, whereas a small but vocal minority rejects the modern efforts in favor of heavier, drier and more durable suit-stuff. In many ways, it is the familiar “new” versus “old” debate in which one side (from behind German, rimless glasses) suggests technological innovation and the other (briar clenched between teeth) bloviates about longevity and tradition. In short, I love my brother but he has despicable taste in cloth. I imagine he would say the same of me.

I suppose wool itself must shoulder some of the blame. It really is too versatile for it’s own good. Italian firms in particular can make worsted suiting of such fineness one might easily confuse it for sheer linen. Conversely, I have held 18 ounce semi-milled worsteds that might prove useful should one suddenly need to refinish a wooden skiff. Confusing things is price. Fine super cloths can be very expensive; the ready-wear market pushes suits in these cloths as luxury items and charges accordingly. Of course a suit made of quality heavy British worsted is also an expensive item, albeit not one adopted by the ready-wear market. There is another layer of complexity too: proponents on either side have launched propaganda campaigns. One side suggests anything heavier than eight ounces is obsolete since the advent of central heating; the other responds with tales of split trousers and sleeves being ripped clean off by a determined enough breeze.

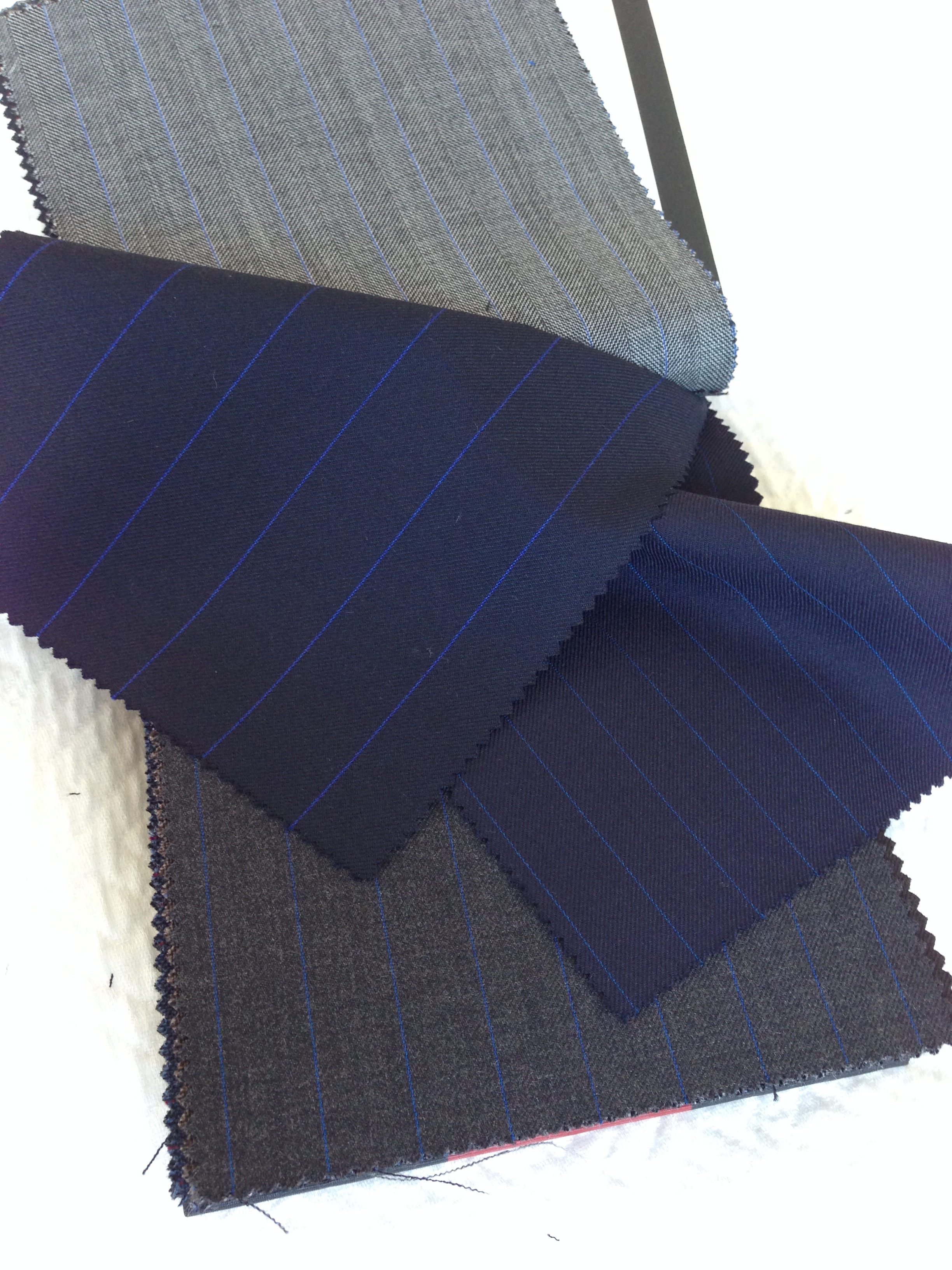

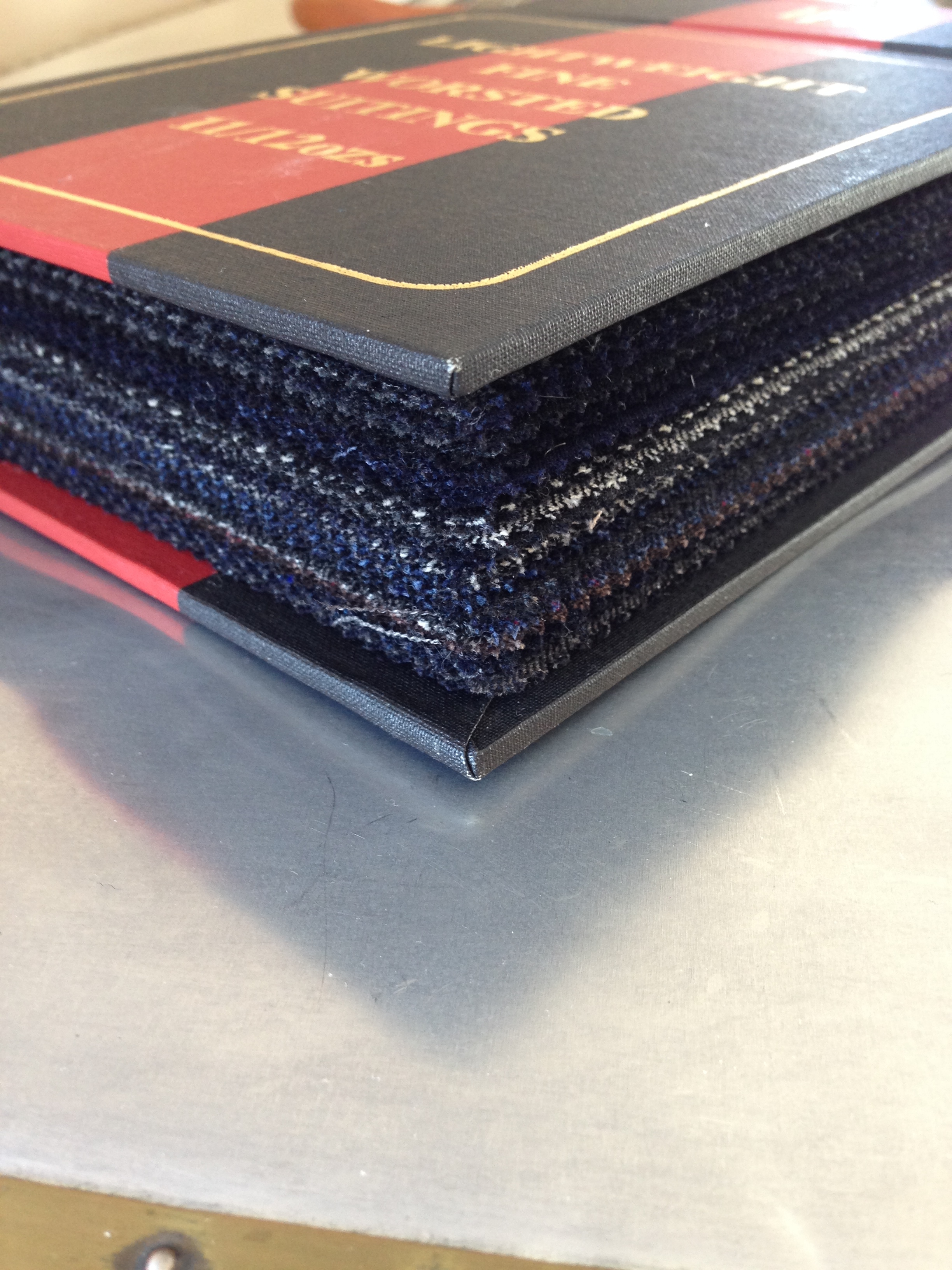

The first suit Chris Despos made for me began life as a navy blazer. I had wanted something sturdy for travel and weekly wear and had considered cloths from twists to serges. I settled eventually upon a 13 ounce hopsack from Lesser’s 303 book. The swatch seemed magical, rebounding from however I crumpled it in my hand and had a deceptive sort of weight at once greater and less than what the book’s cover indicated. I’m not sure we made it to a second fitting before we decided to add trousers.

I realize opinion on a 13 ounce, densely woven hopsack suit might be divided. It would positively send my brother to the funny farm. But I must admit an obsession with the garment. The depth of color is remarkable, managing to be unmistakably navy and not black or blue, a fate many a “navy” suit suffers. The subtle weave is dead-matte in daylight, with enough surface interest to seem at home with madder, knit or woolen neckties. It transforms at night, though, when that surface awakens with lustrous depth and richness enough to set off the sheen of foulard and satin. Most importantly though it feels to me like a suit of clothes rather than a set of pajamas, a quality that should not be dismissed considering this suit has become my favored choice for more serious affairs where one might appreciate not feeling so exposed.

Speaking of pajamas, a few months after his own wedding my brother was invited to an old friend's own nuptials, another Brit living in New York. He was looking forward to the event until he learned the bride wished the groomsmen to wear morning suits. My brother has lived in the States too long to necessitate morning clothes and so was compelled, along with five other saddened individuals, to rent. On the day, the itch from the burlap-like cloth became so severe he felt he had no choice but to stop at a mid-town discount mall and purchase flannel pajamas which, despite a high in the mid-80s, he wore beneath for the duration.

Oh how I wish I had that gem the night of my speech.