The Oddest Jacket

When said aloud, the problem sounds trifling: I don’t have an odd jacket that performs well in the heat. But who hasn’t wilted through some jacket-wearing event, sorely tempted to ditch the offending top layer at the first hint of relaxed formality? I was at a garden party last summer where jacketless-ness spread like a fast-moving flu. I resisted, and was ostracized by the damp-shirted other men who looked upon me as if, instead of tobacco linen on my back, I wore a scarlet A upon my breast. Why the hostility? Misery, or in this case steps taken to lessen it, likes company.

At the core of the matter is an existential problem for the garment in question: why try and beat the heat with a jacket, when its absence is more effective? And yet the garment endures, relevance be damned, in a suspended state of compromise. Whatever other people’s motivation in wearing one, mine is split sixty/forty utility/propriety. Utility gets the edge because I simply do not know what else to do with a phone, handkerchief and keys. Introduce sunglasses, or, if leisure is the goal, a cigar and lighter, and one approaches tote territory. The social expectation to wear a jacket, when not required to wear a suit, is less concrete. Some men persist out of habit, others are obstinate traditionalists; some begrudgingly comply, still others embrace the vanishing requirements without giving the matter another look. I suppose I fall somewhere between the first and second fellow, but propriety still accounts for only forty percent of my motivation. I will say this though: even at the more extreme ends of the temperature spectrum, when a jacket seems correct, it always is.

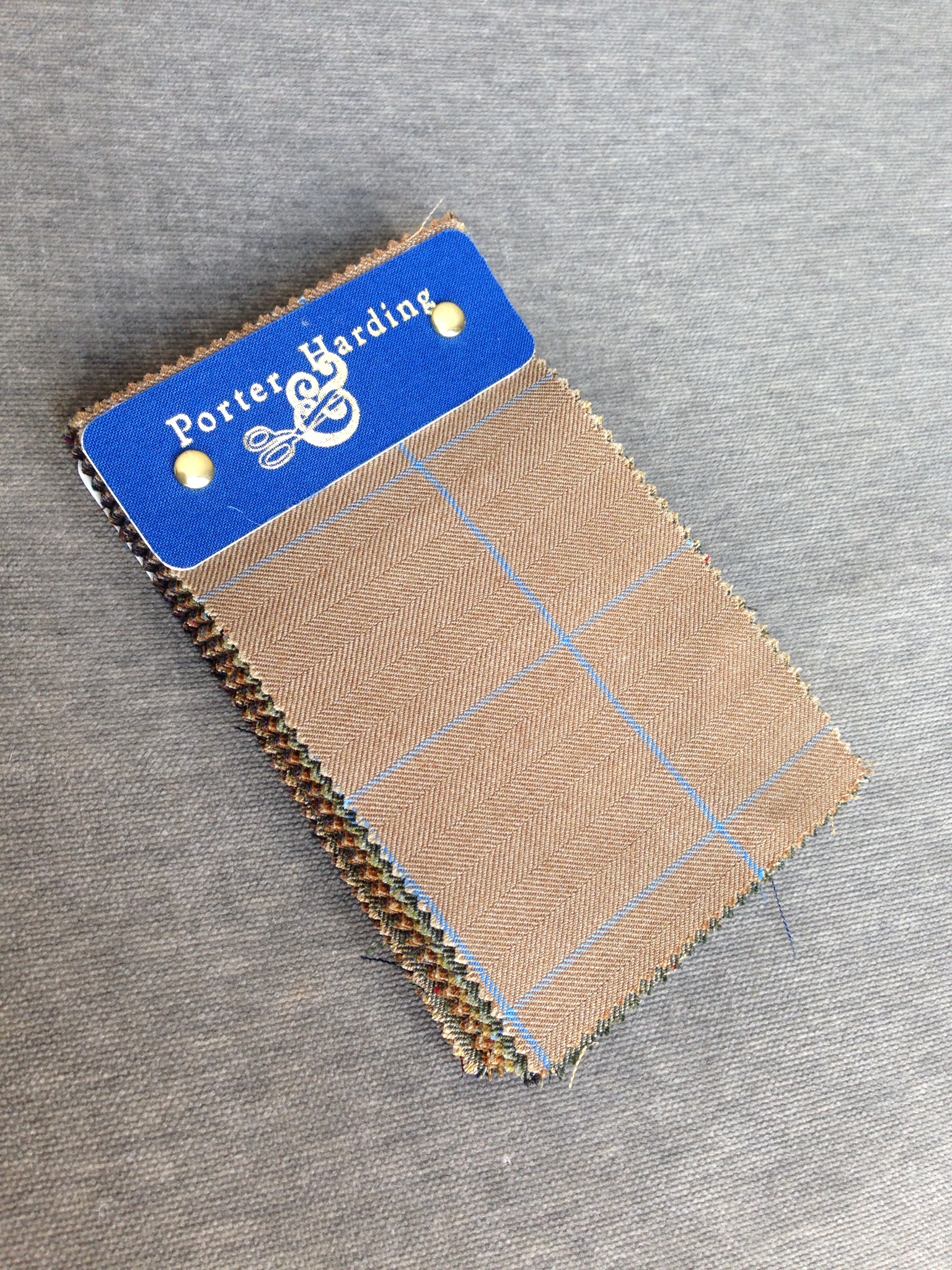

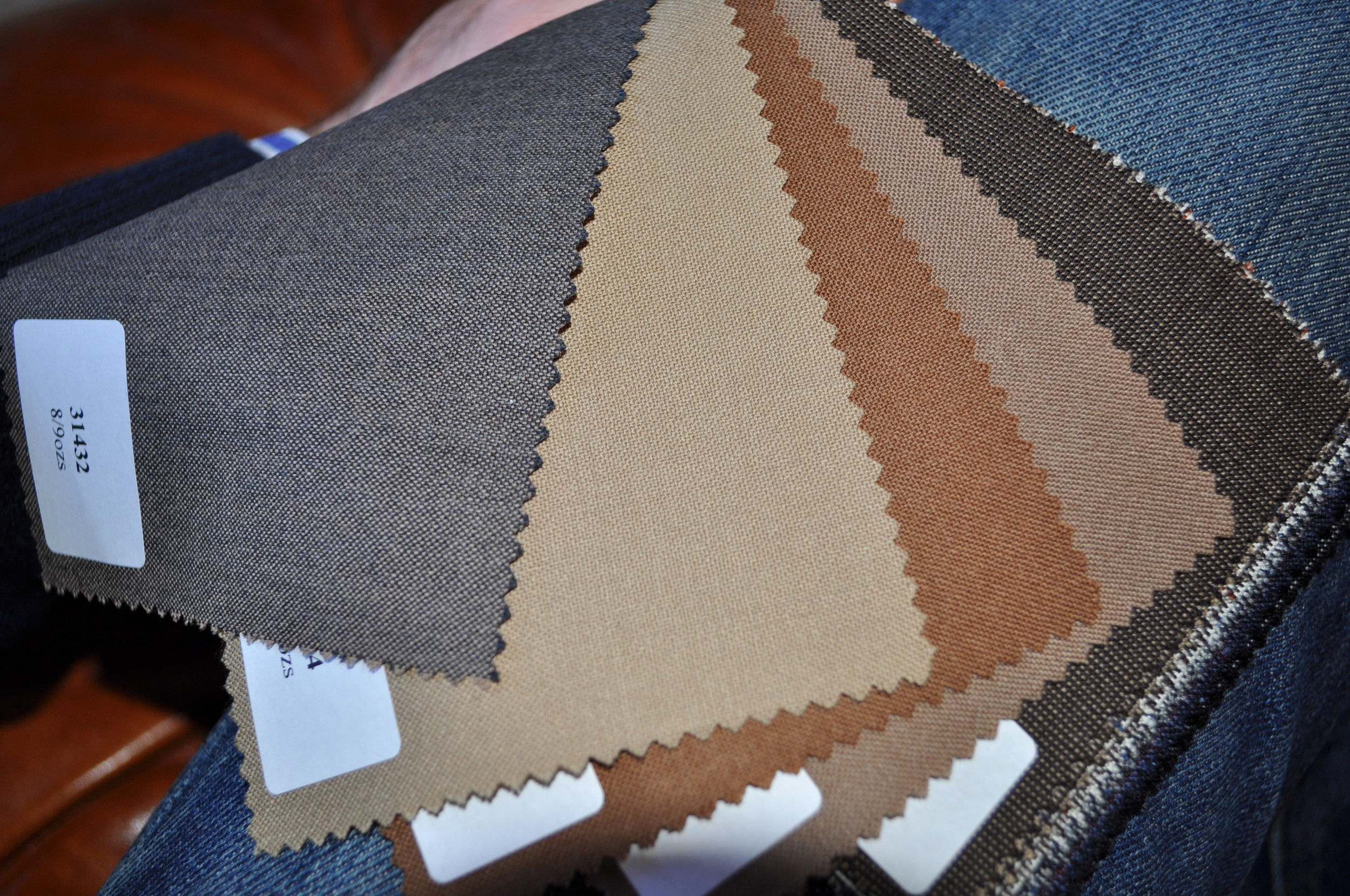

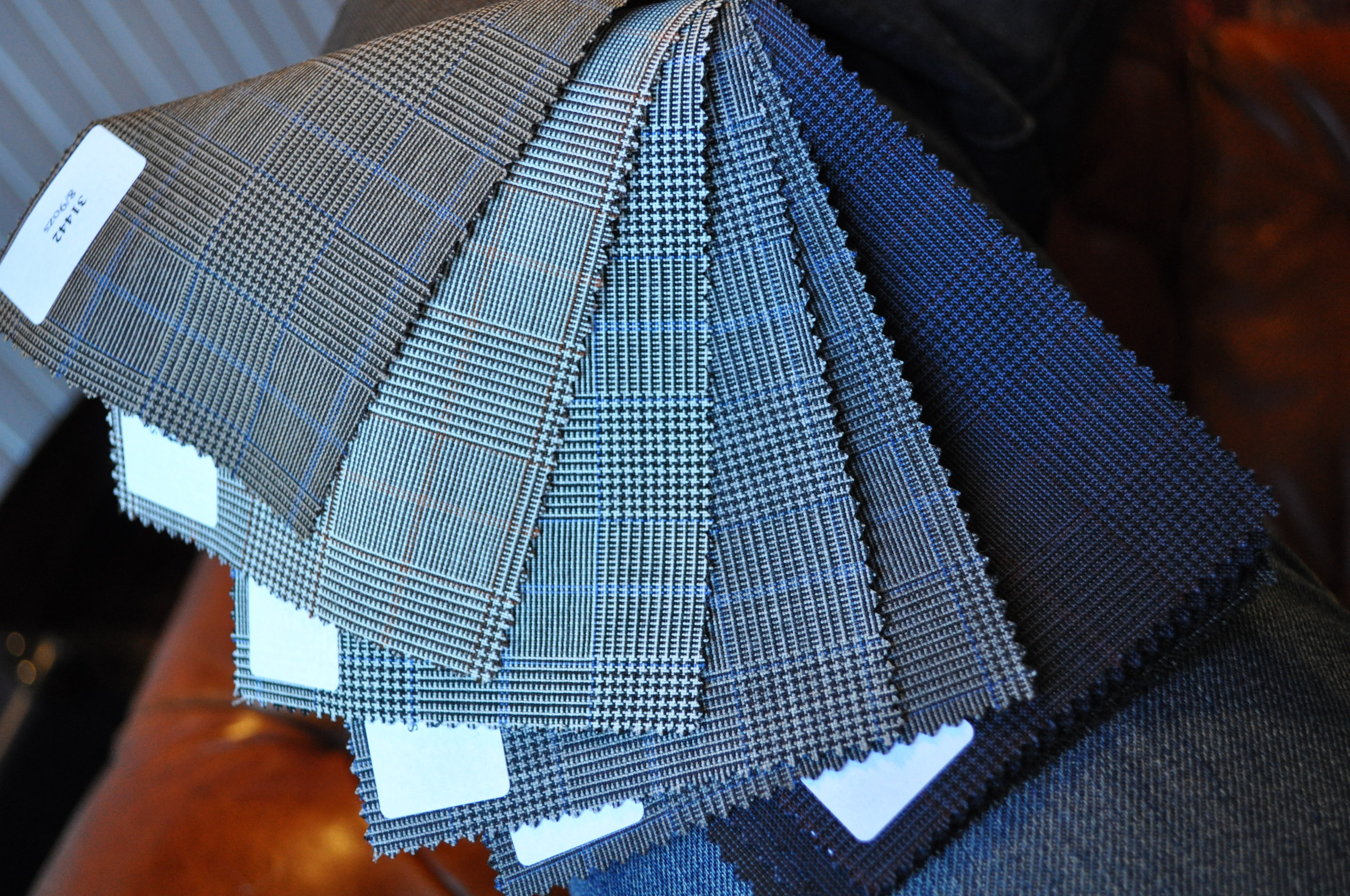

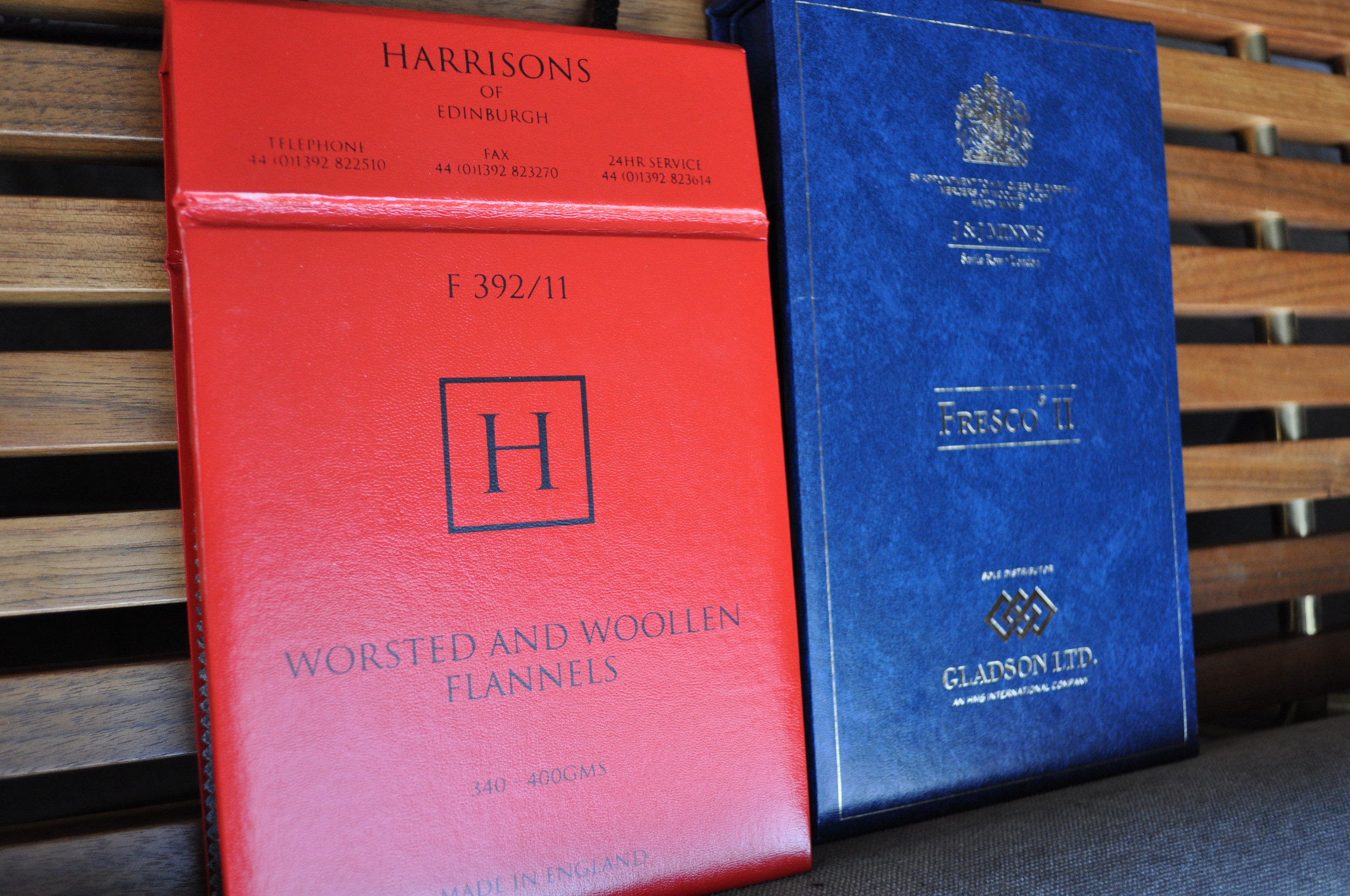

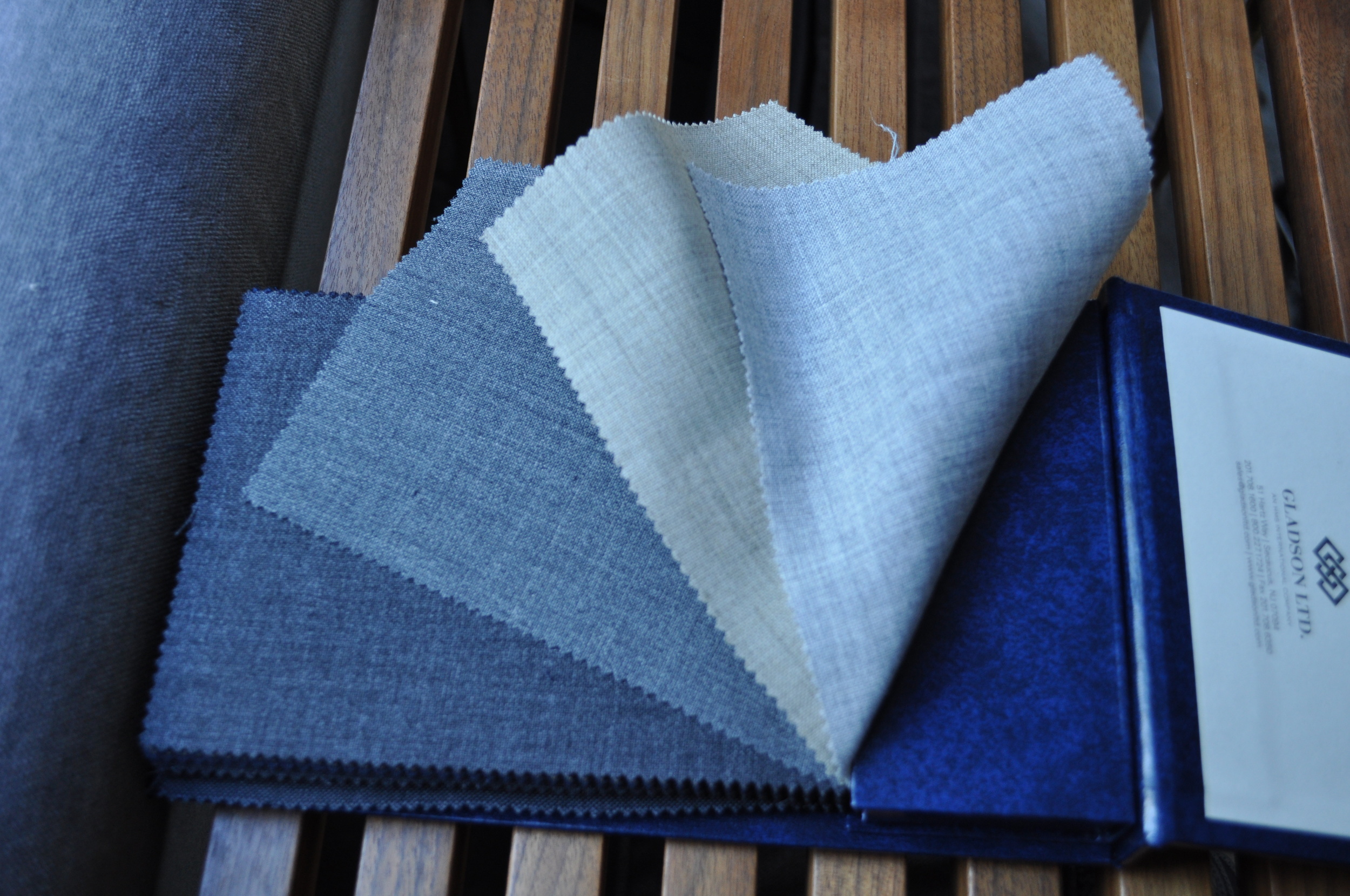

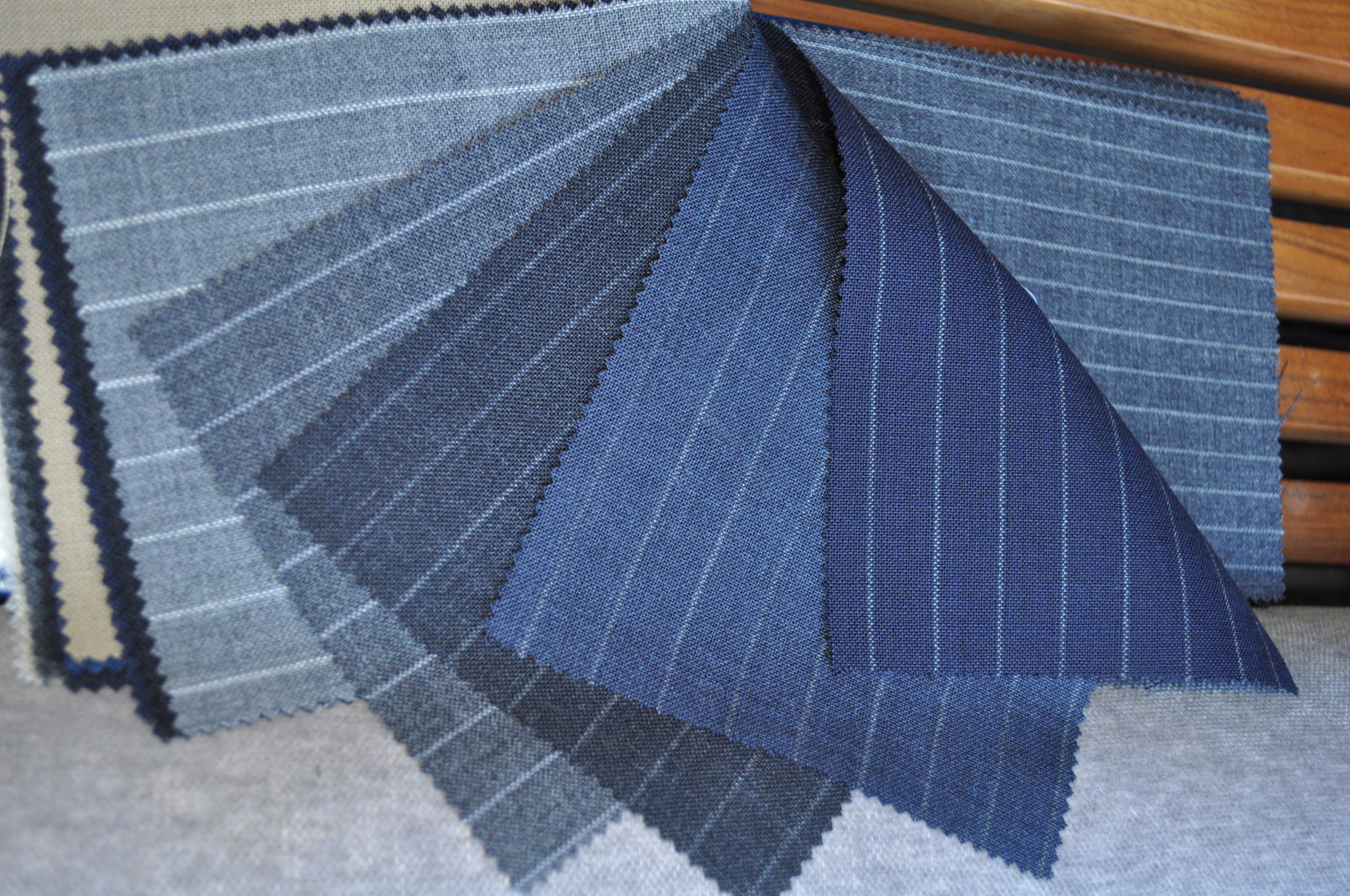

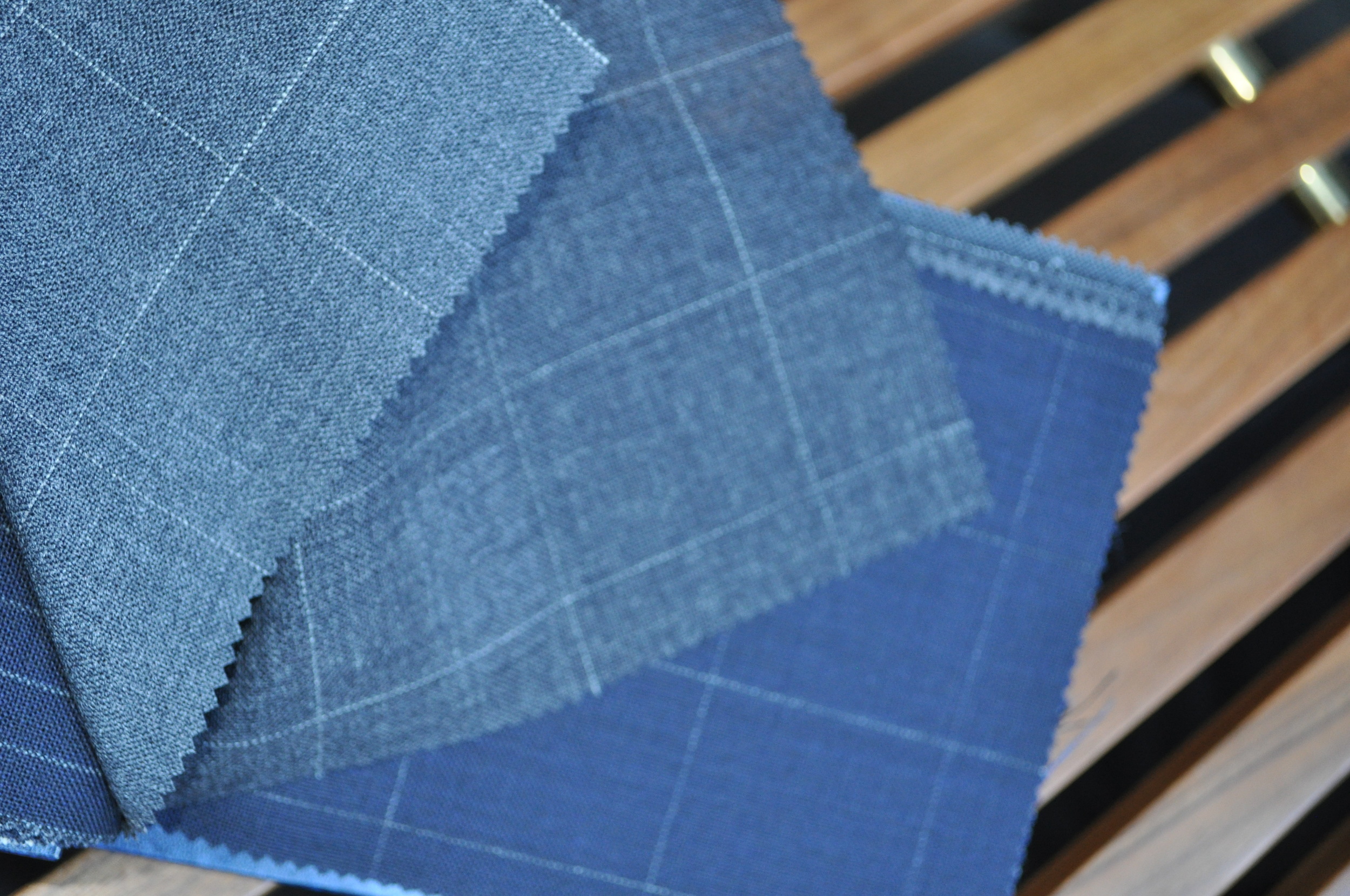

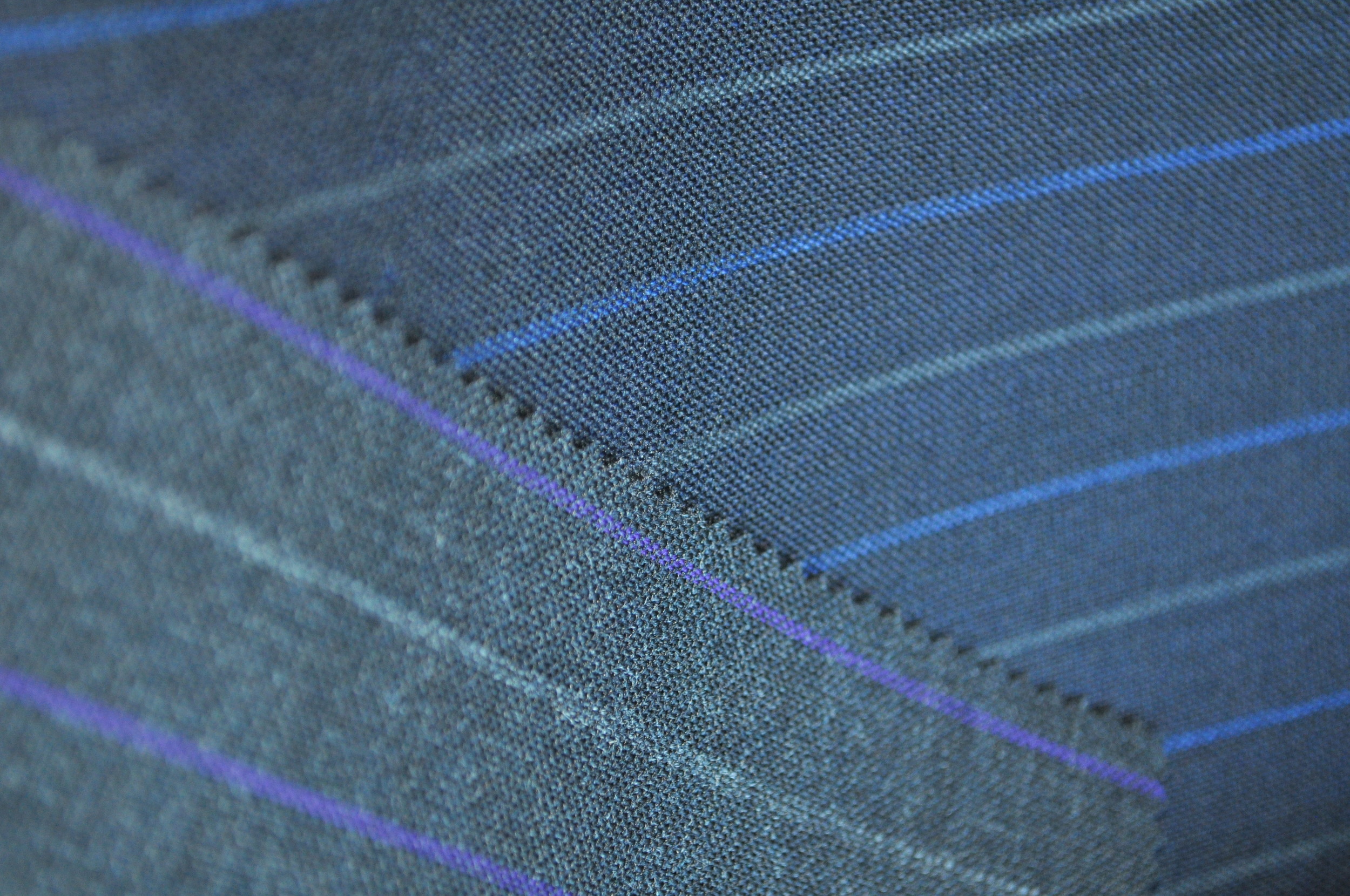

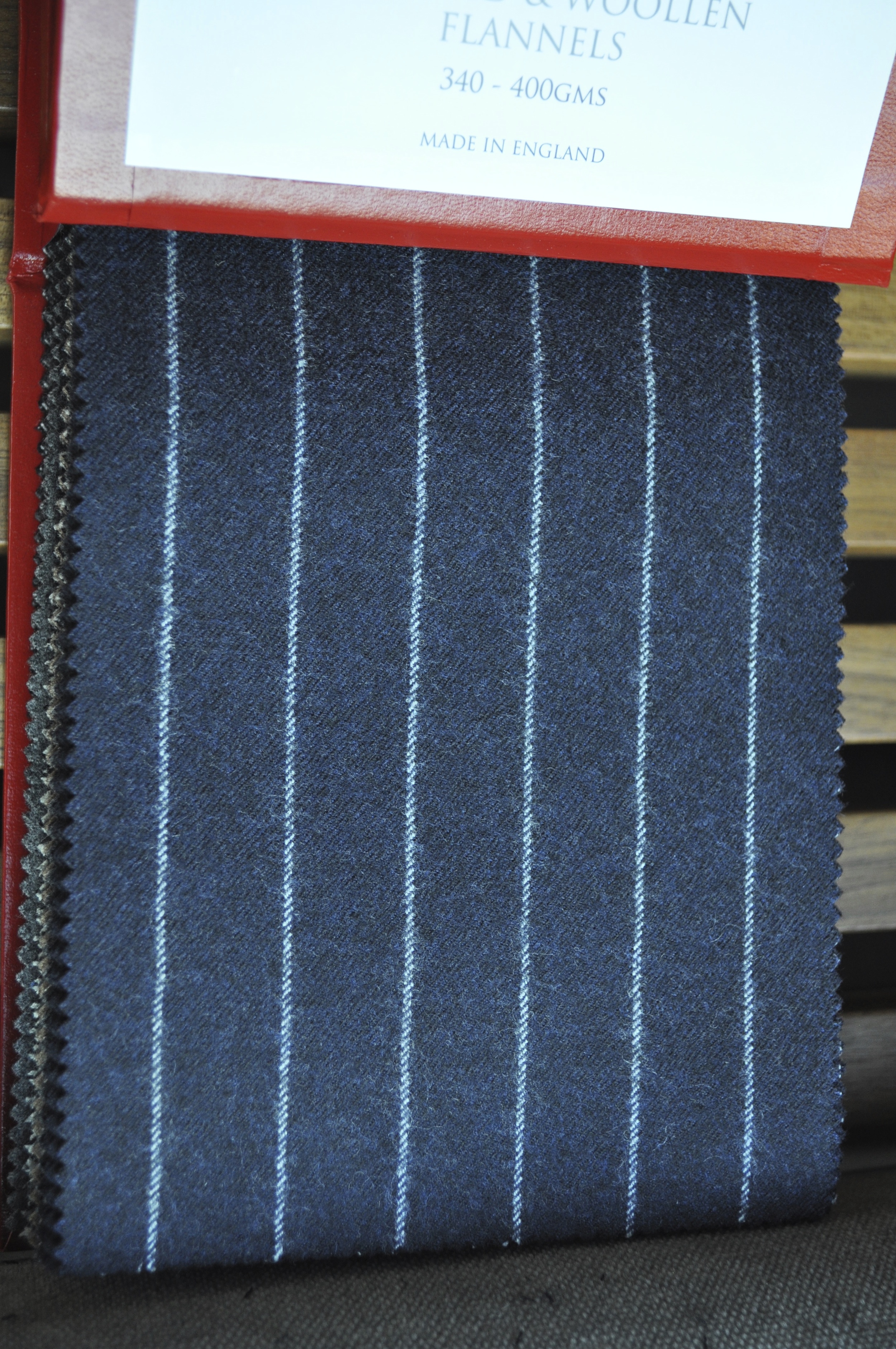

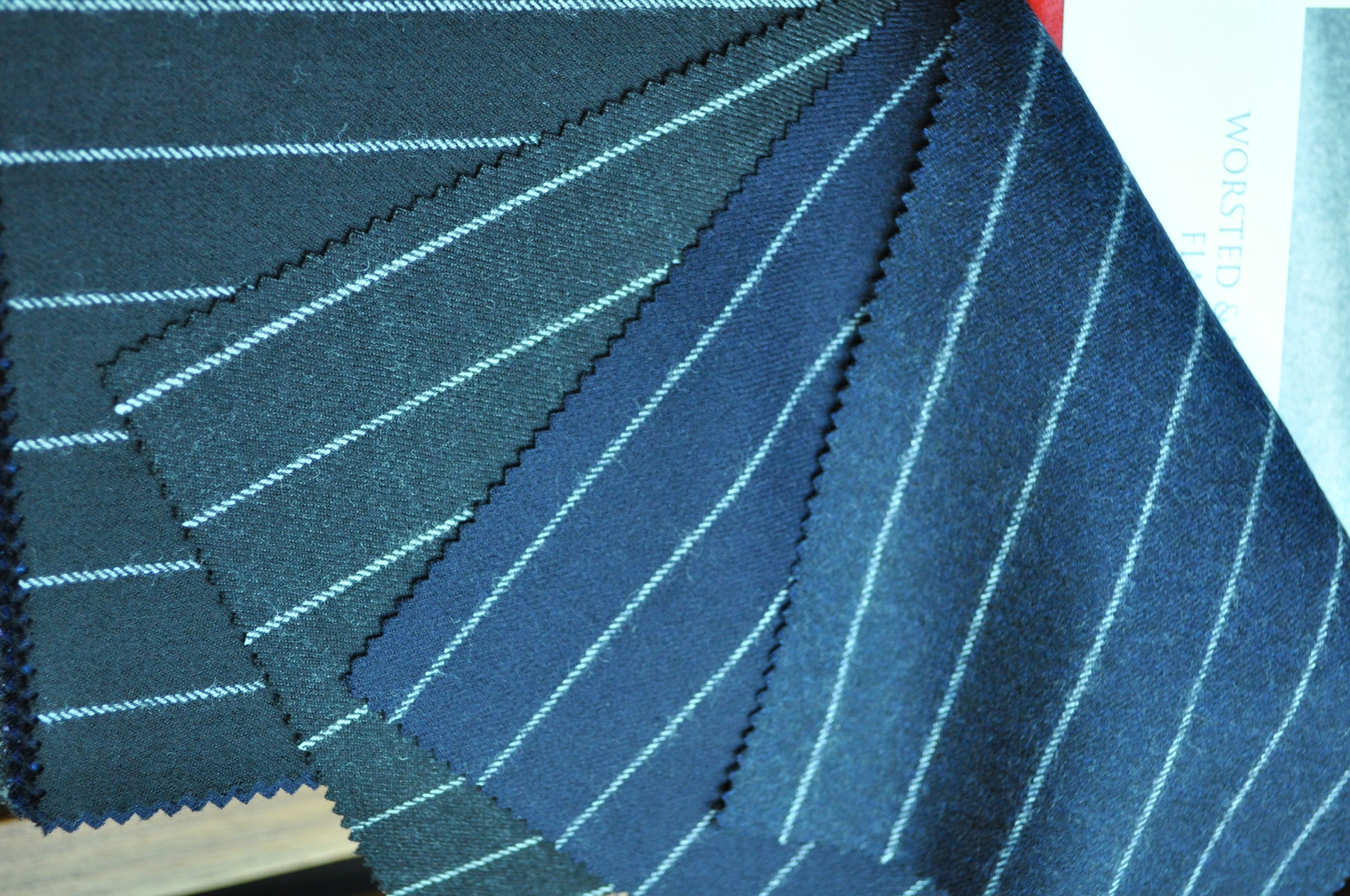

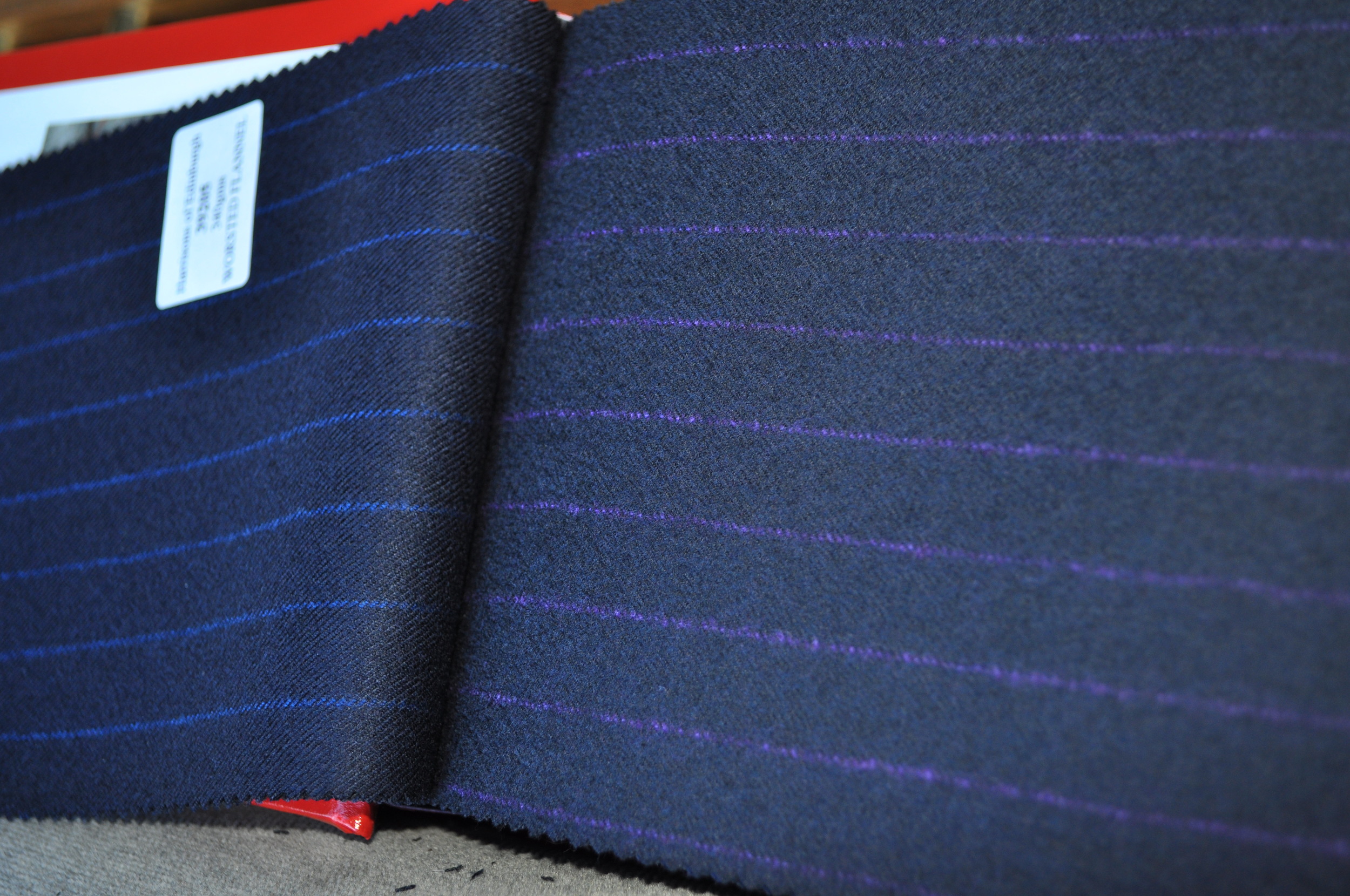

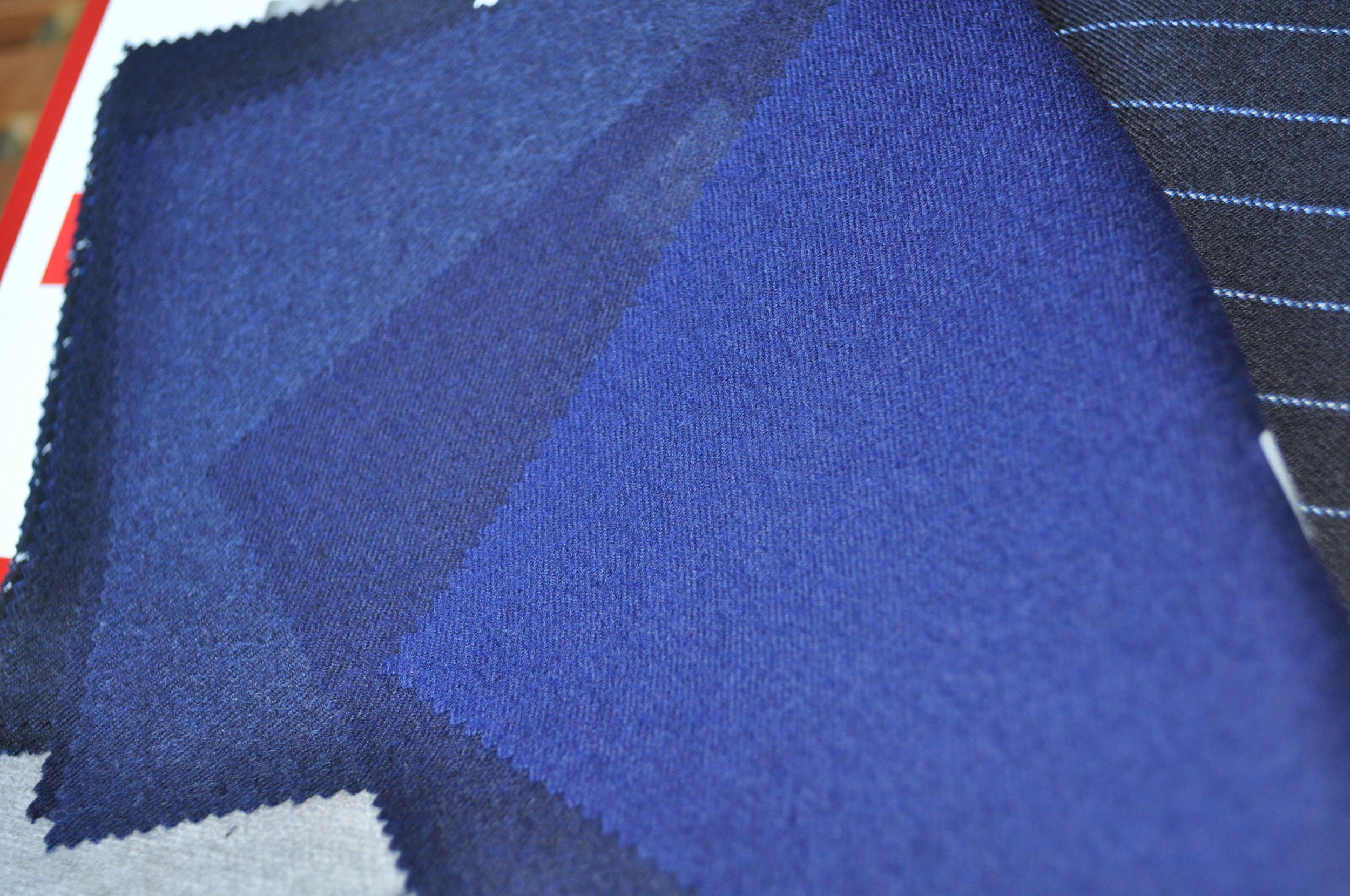

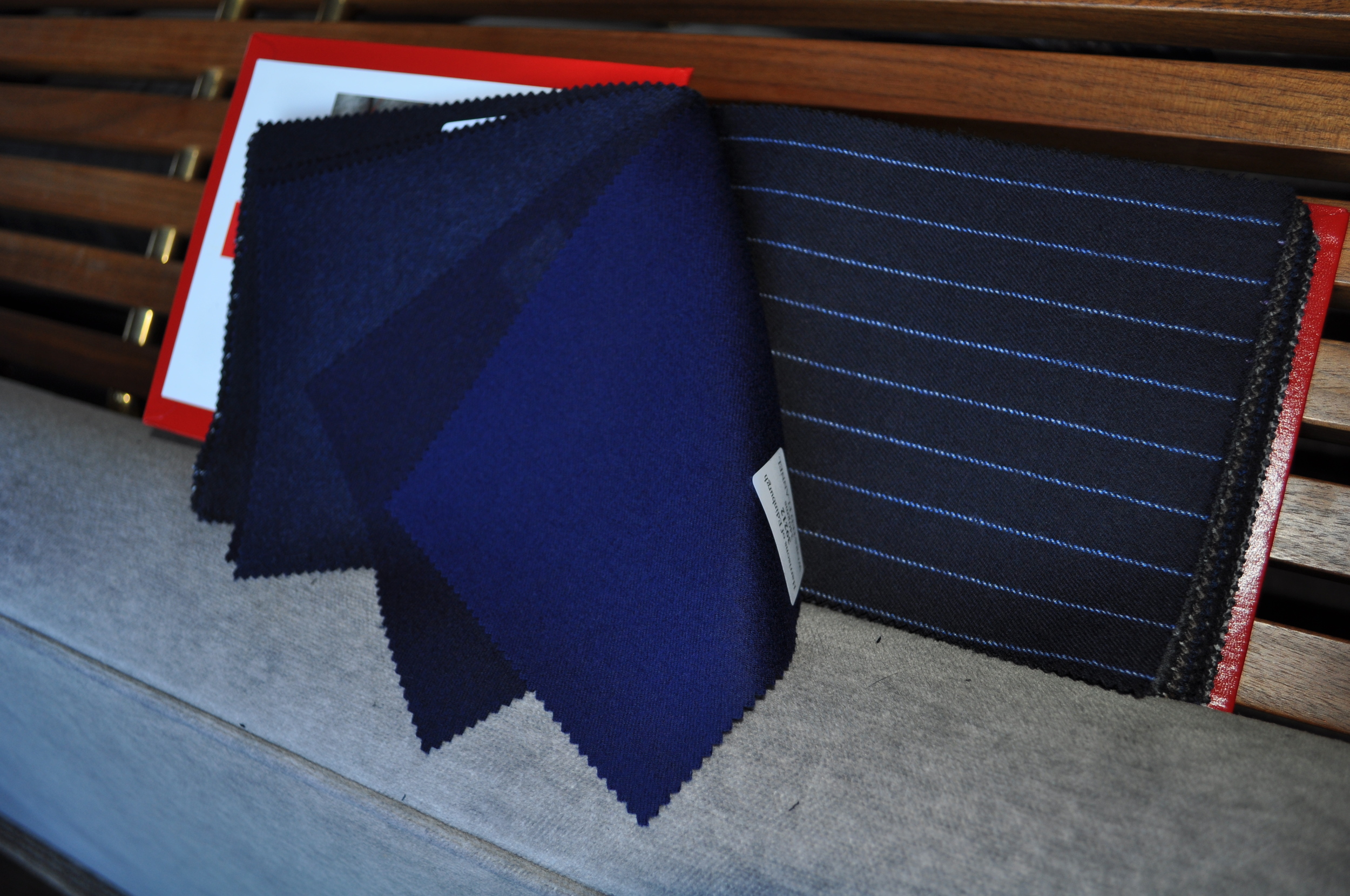

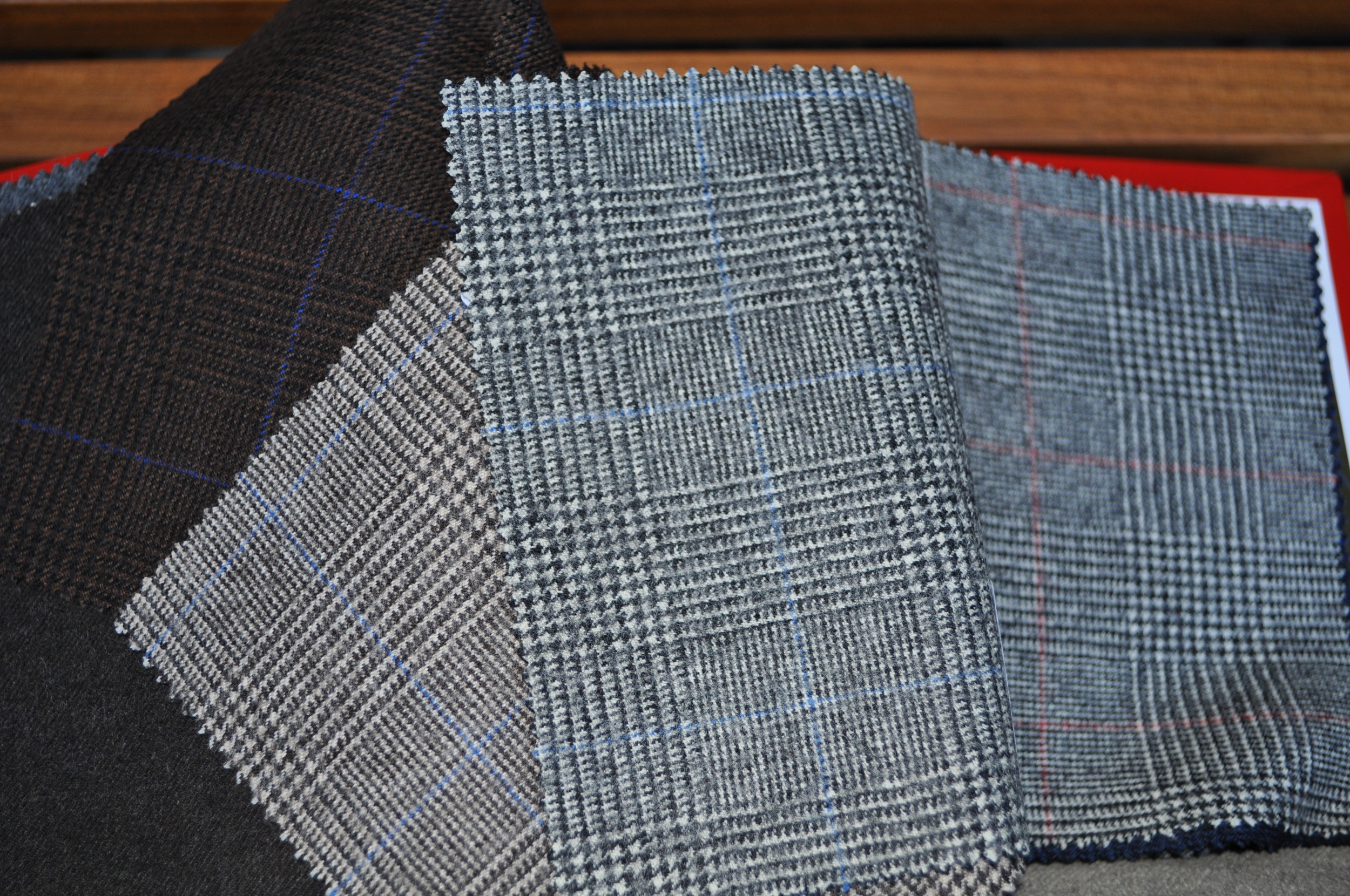

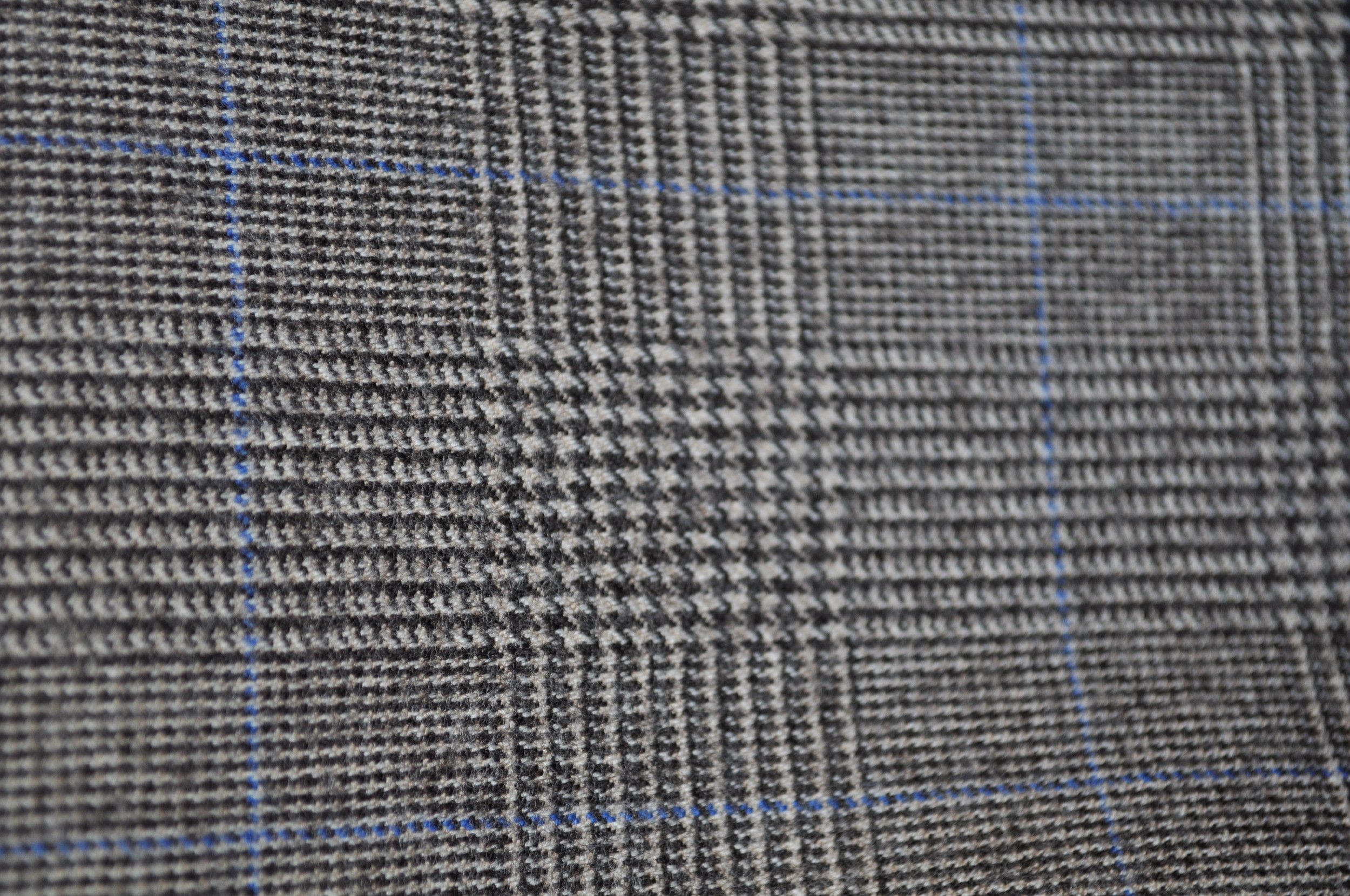

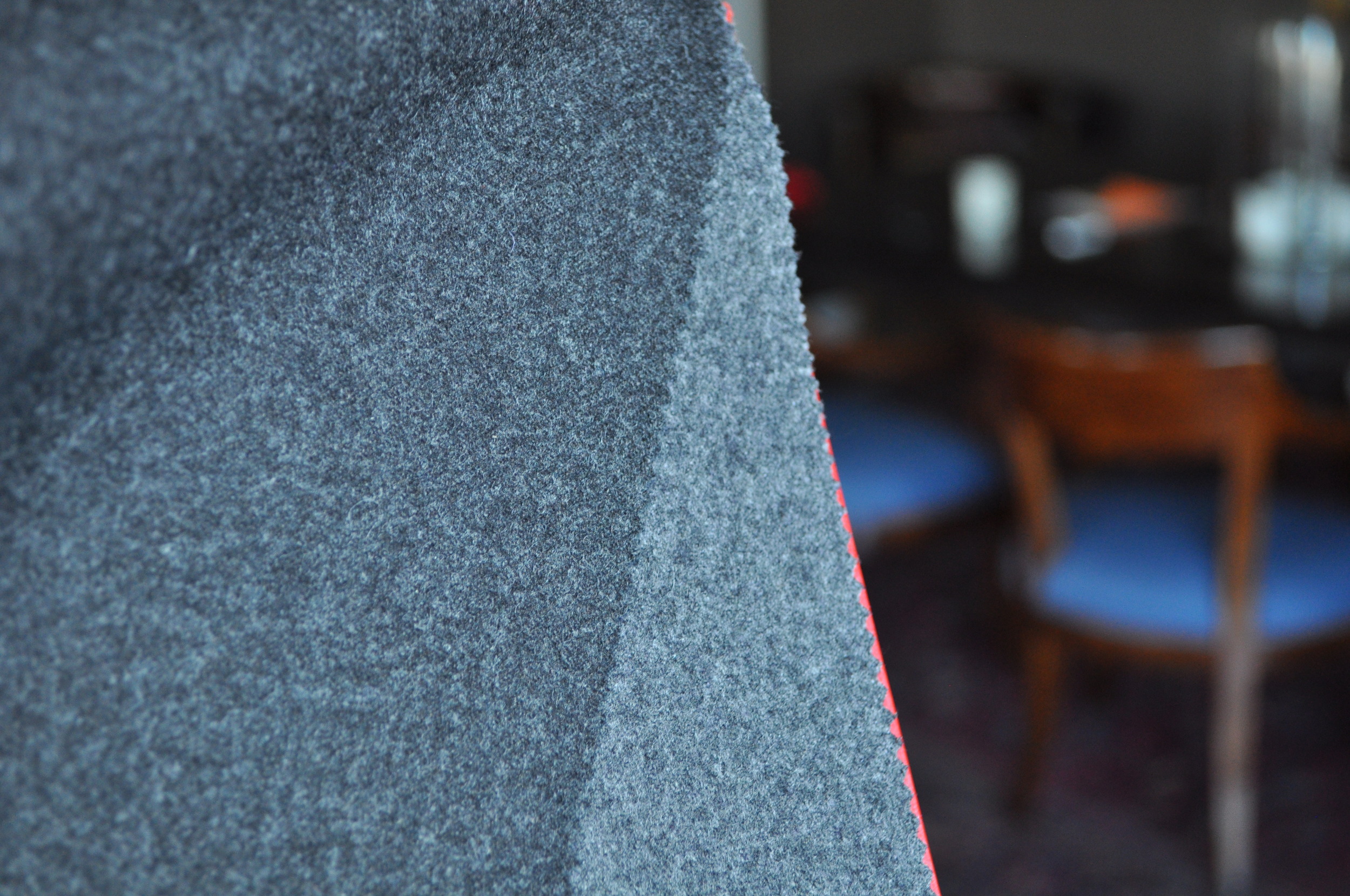

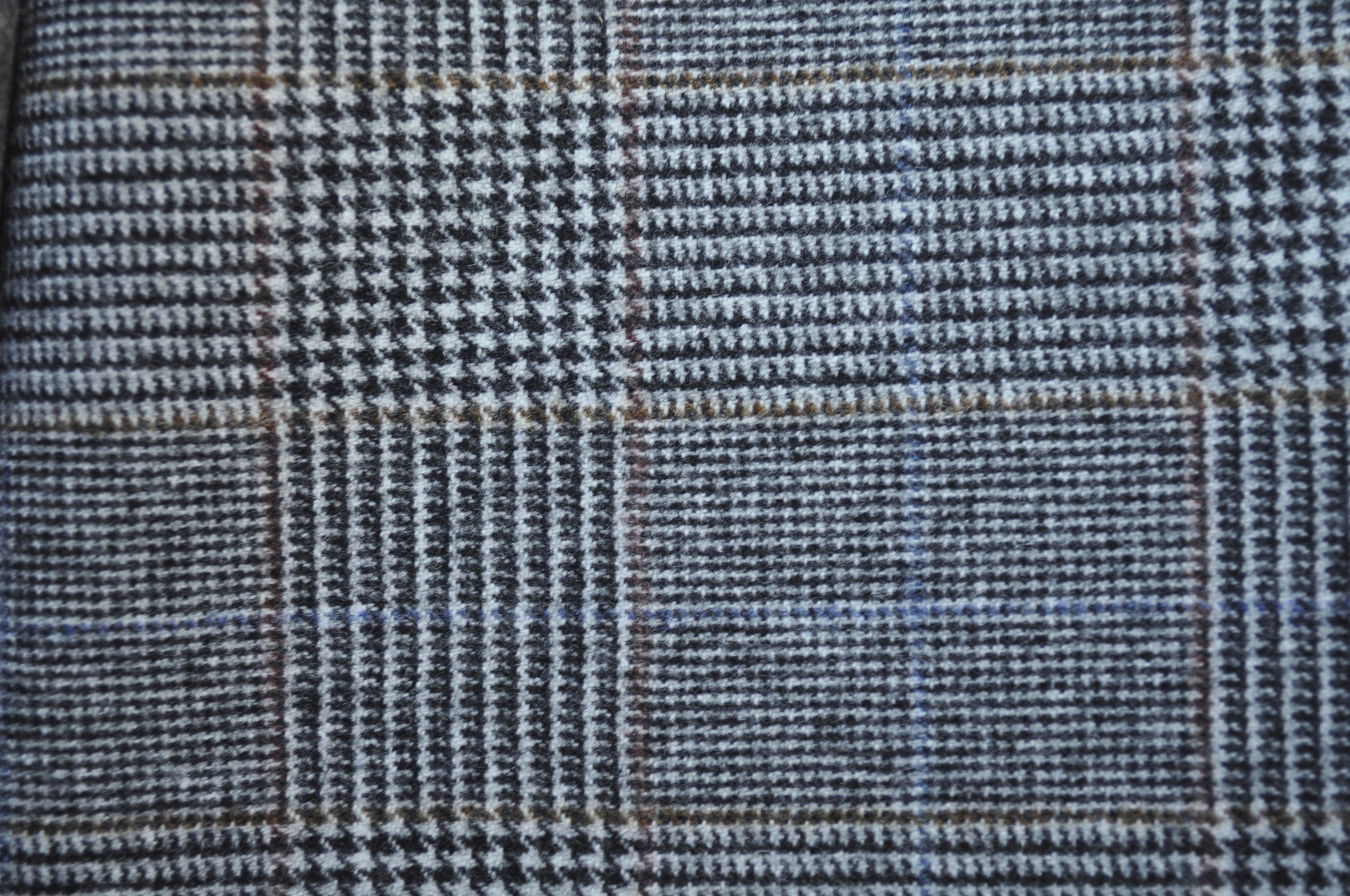

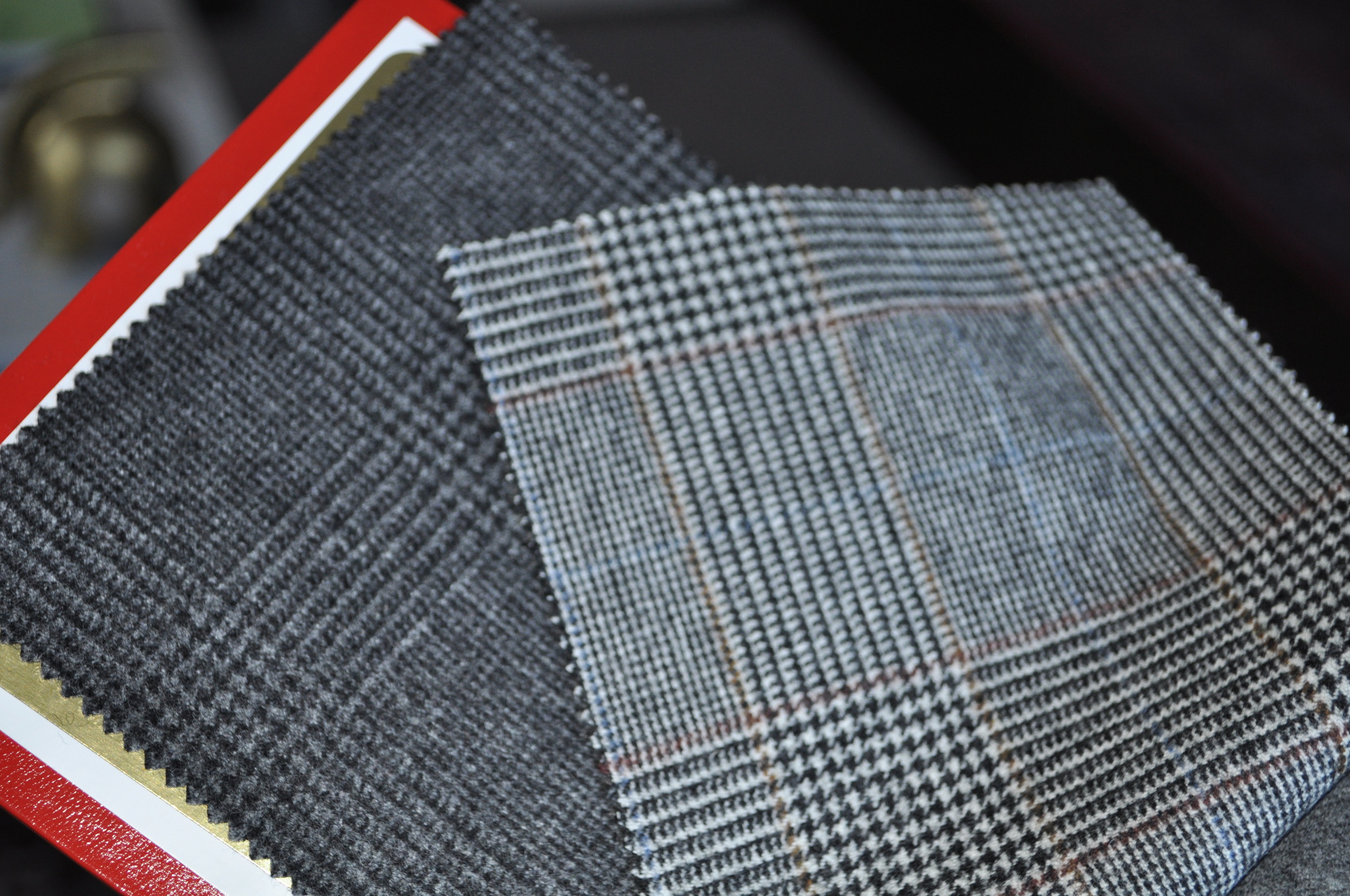

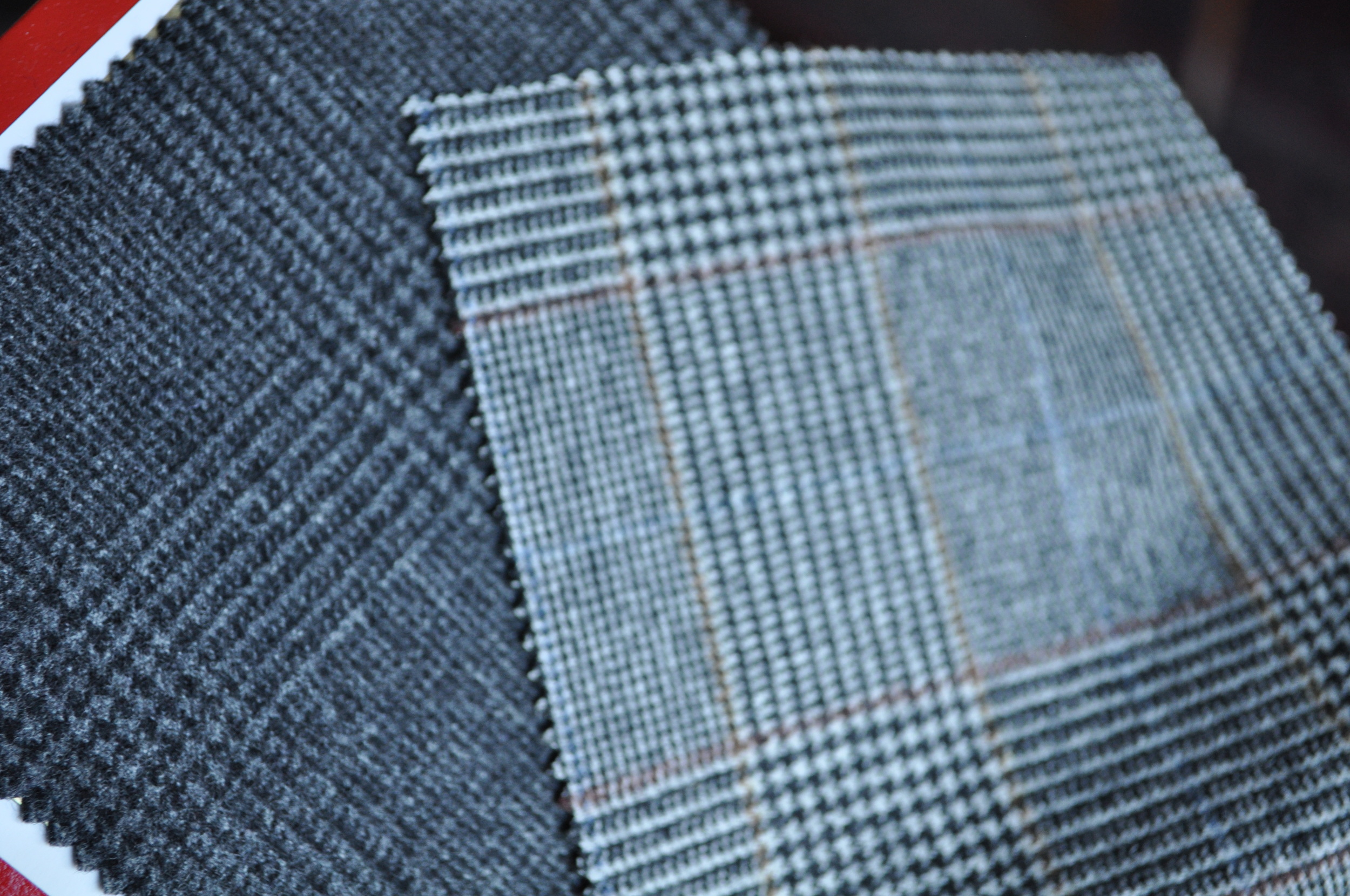

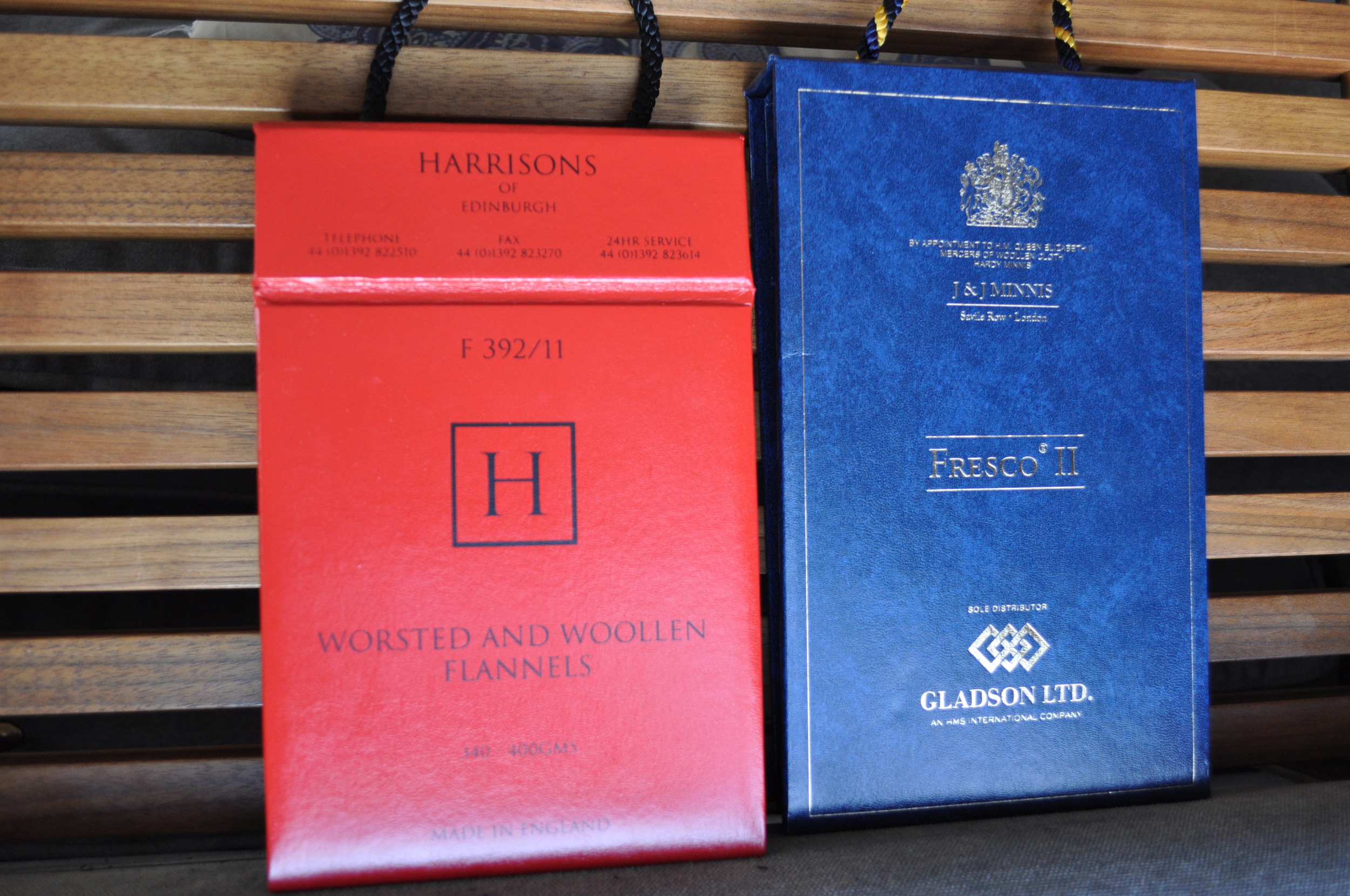

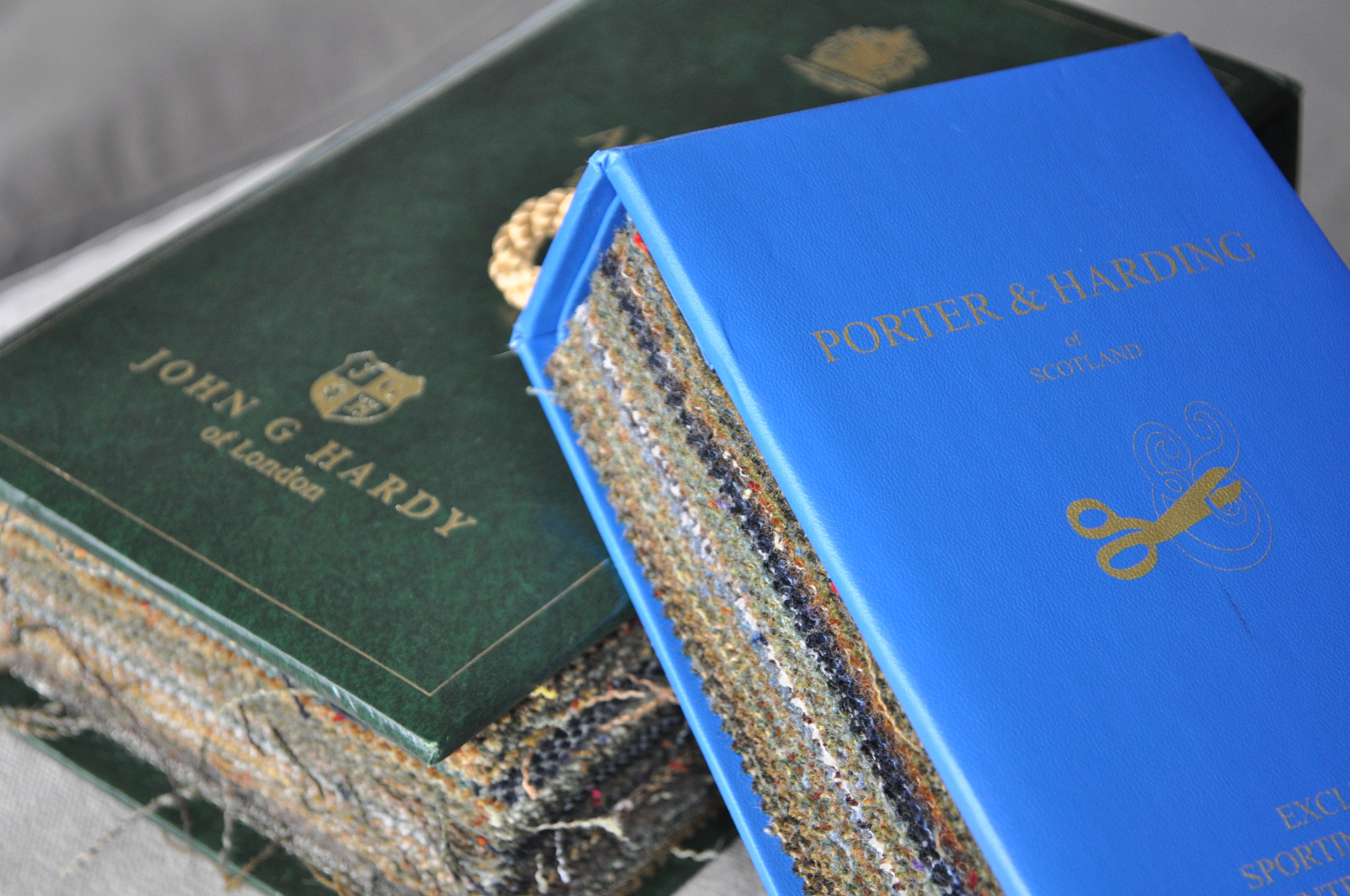

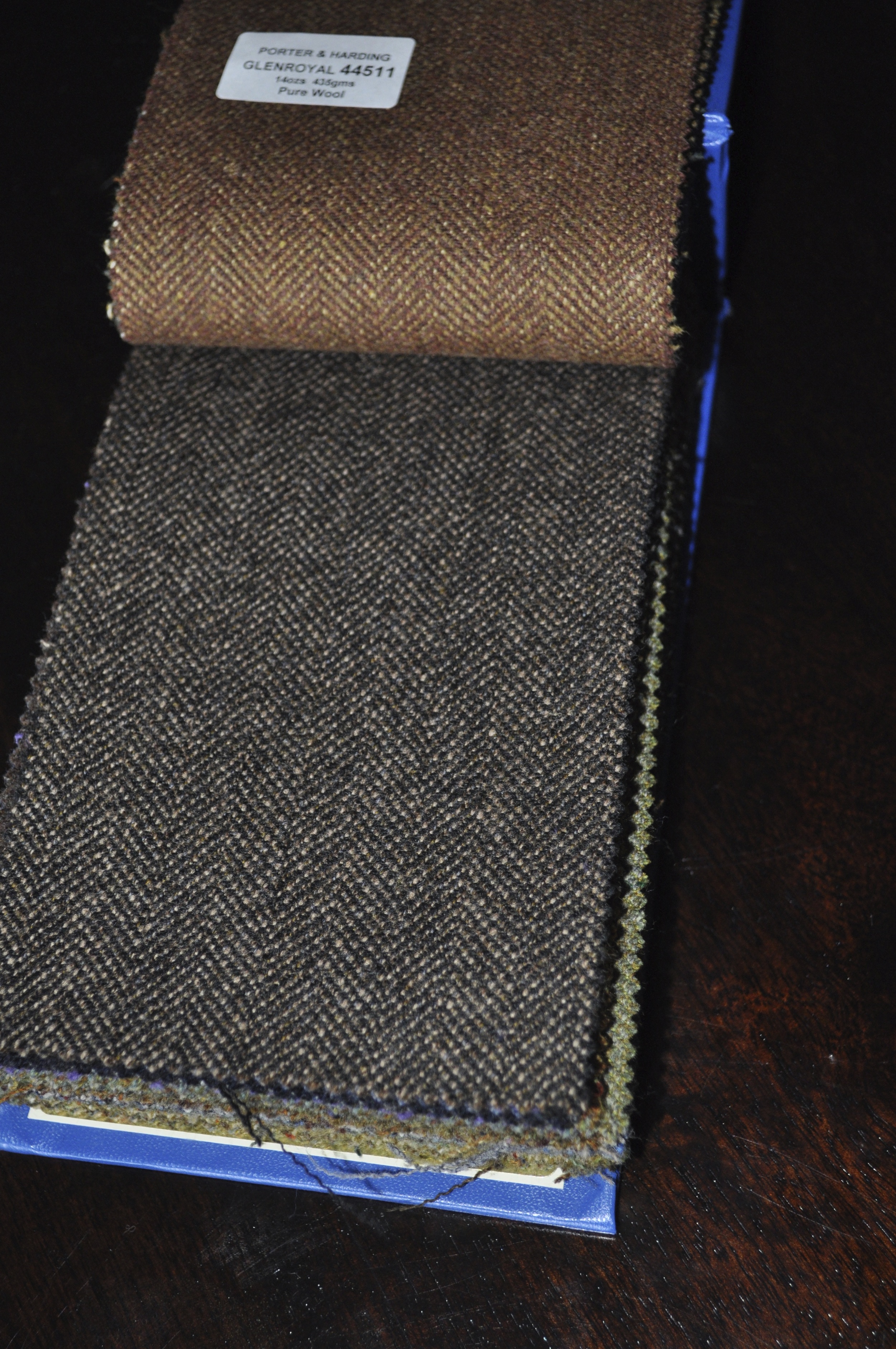

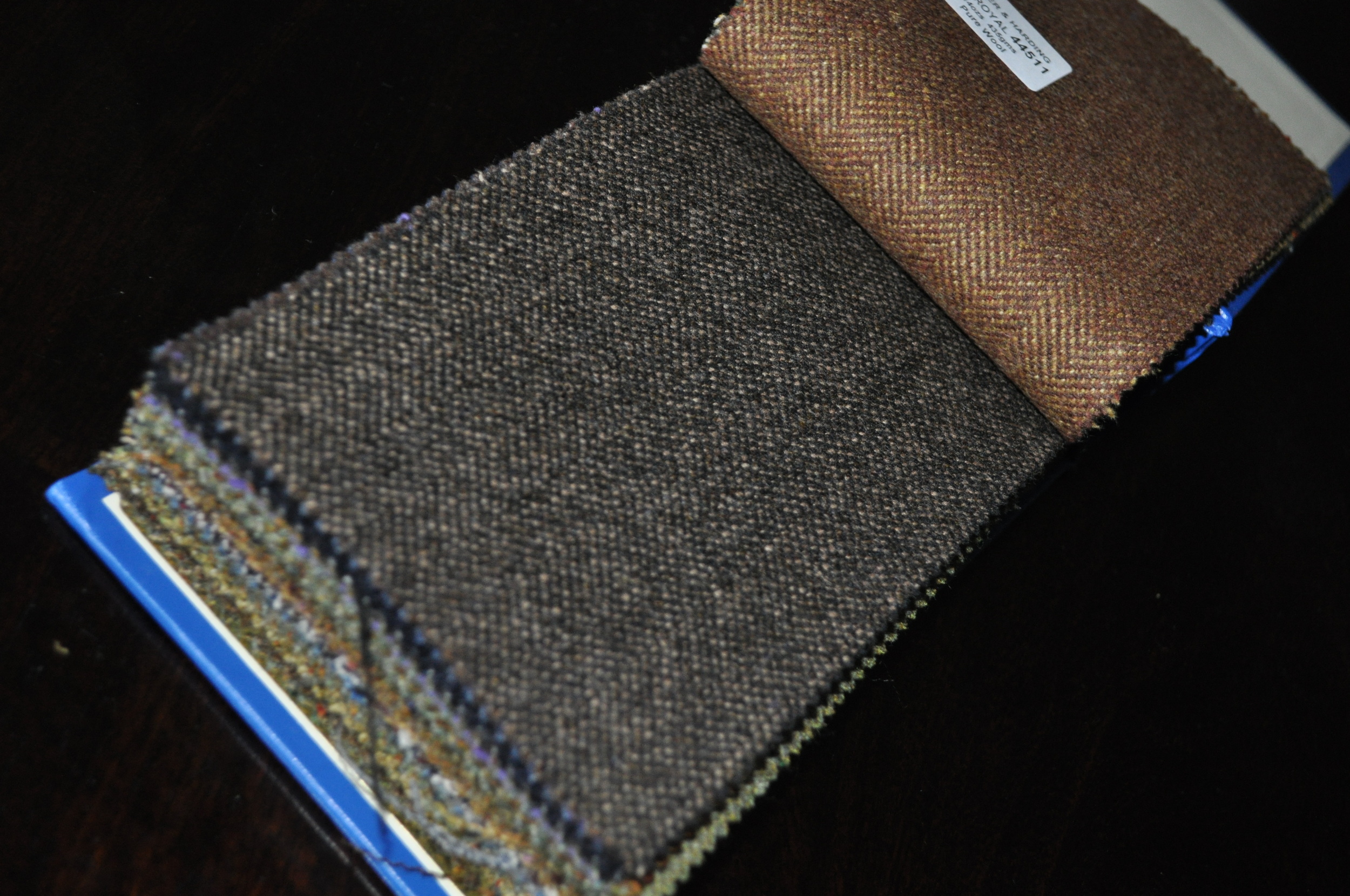

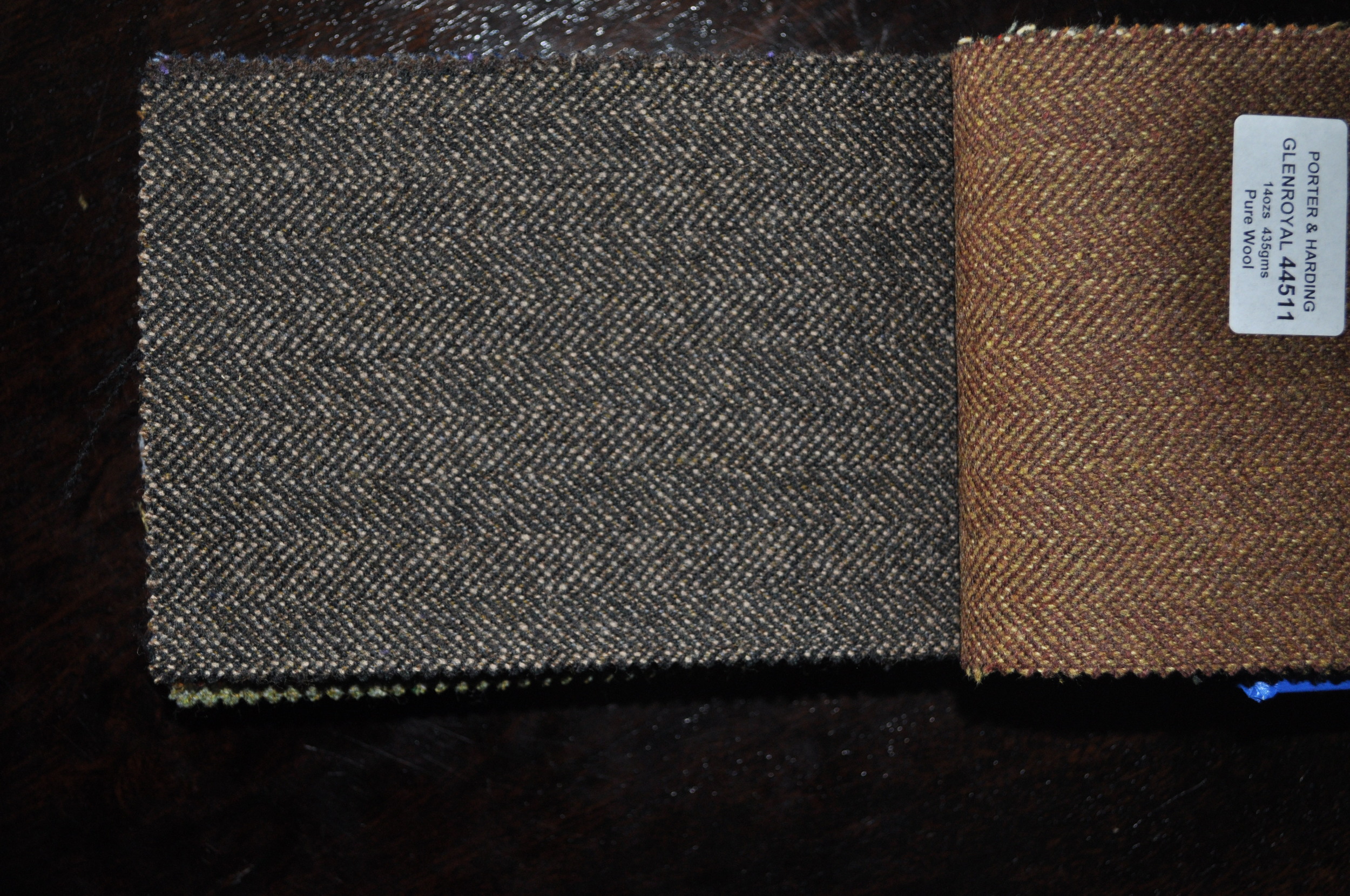

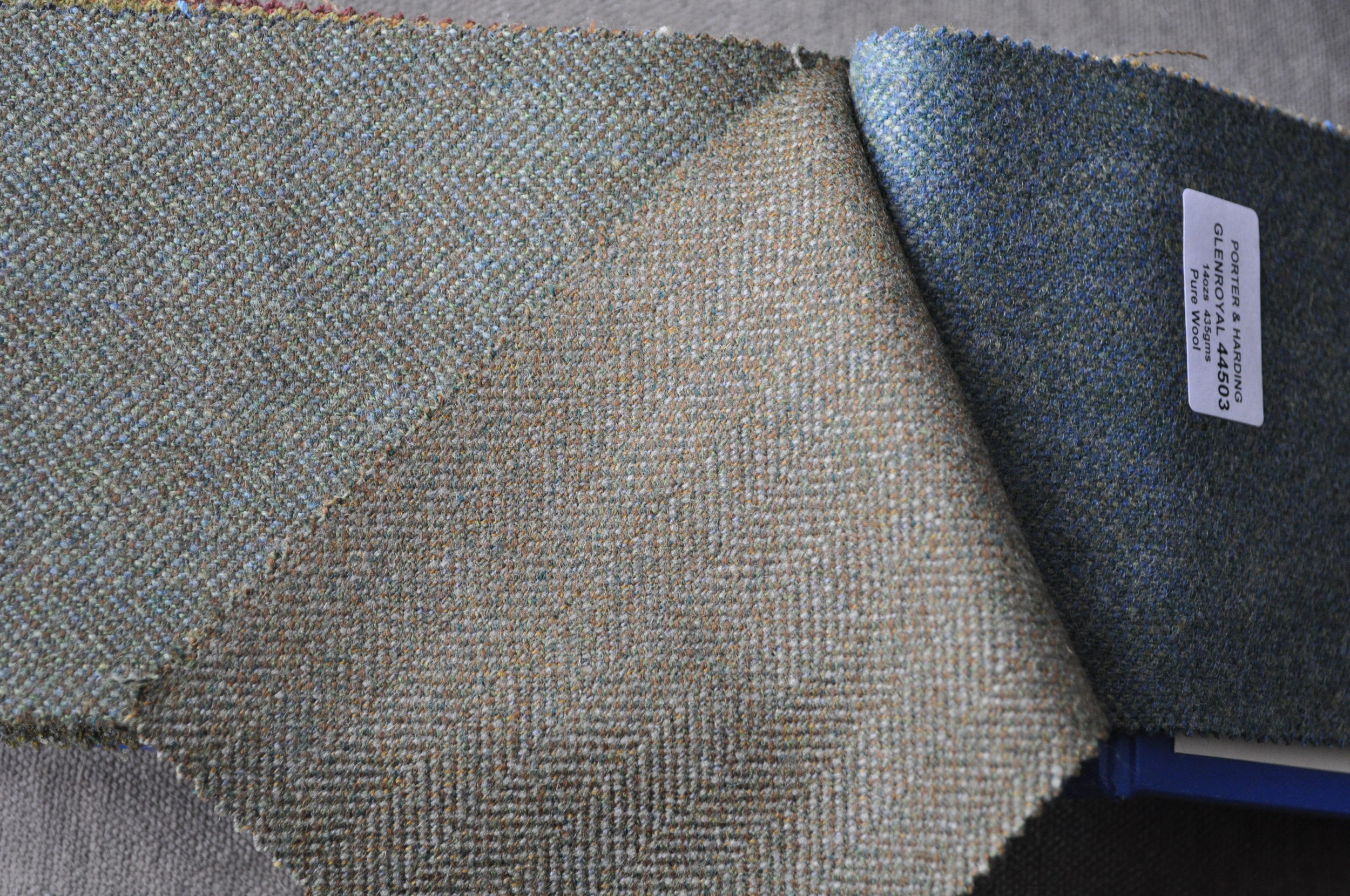

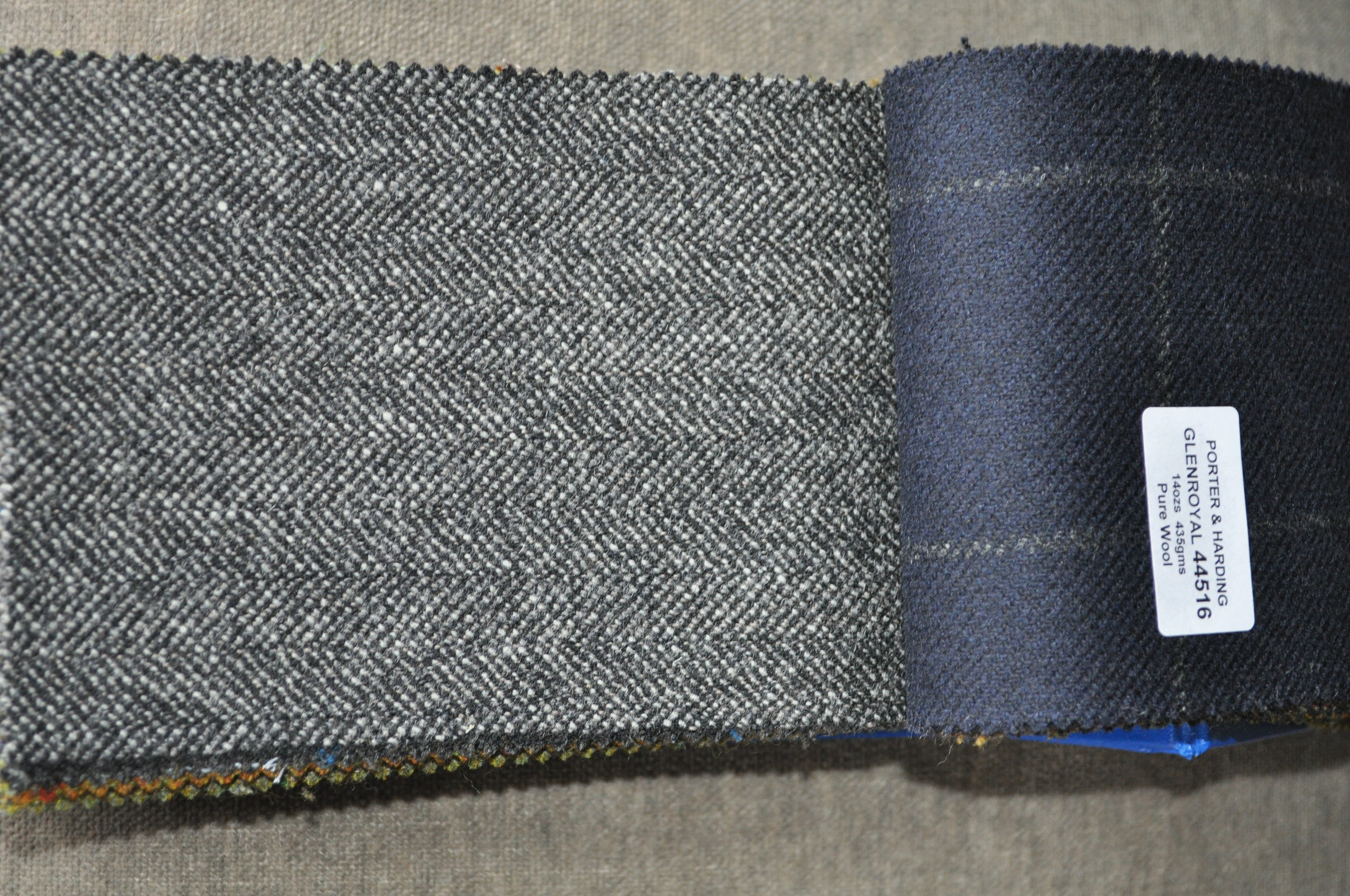

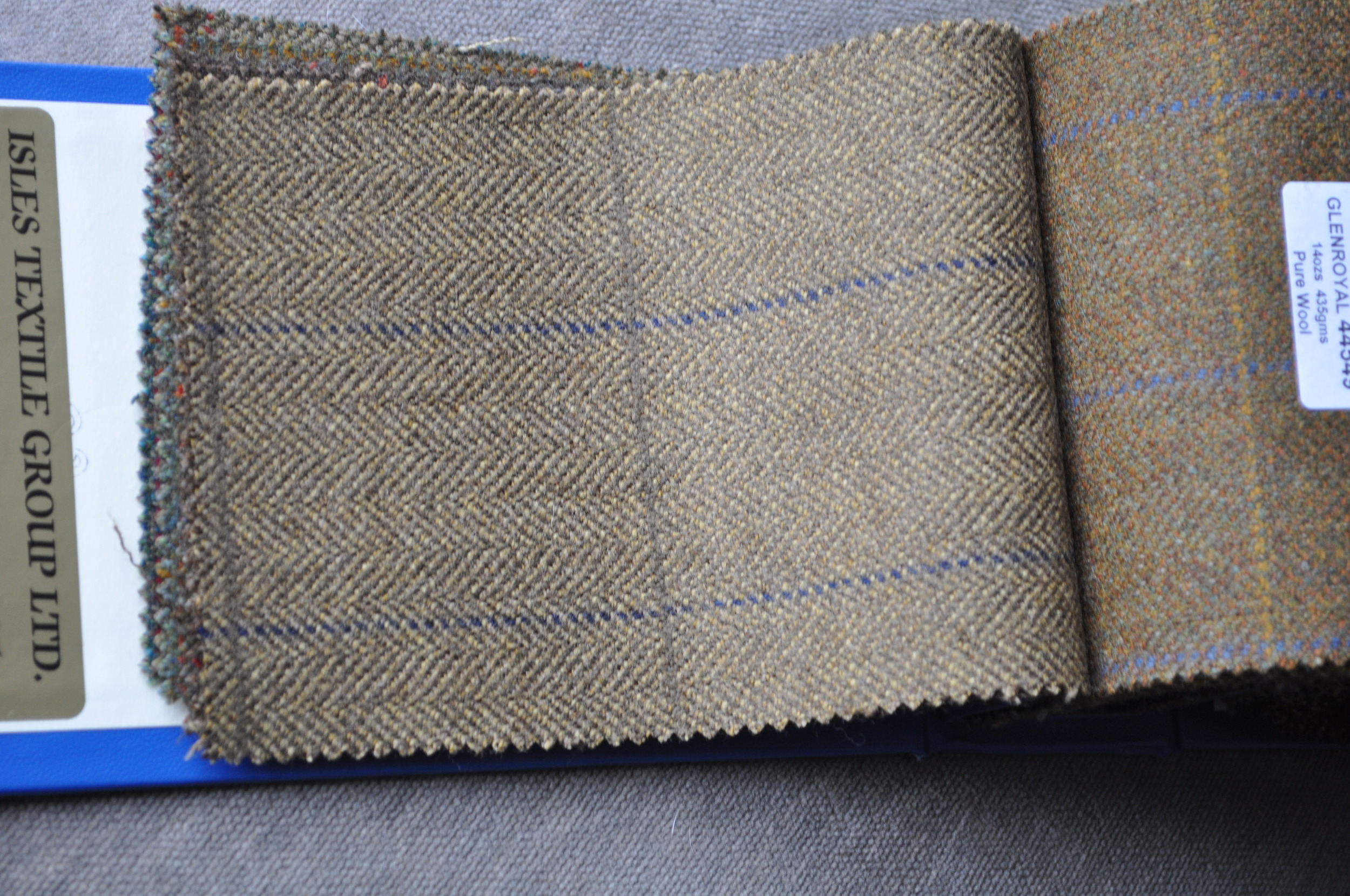

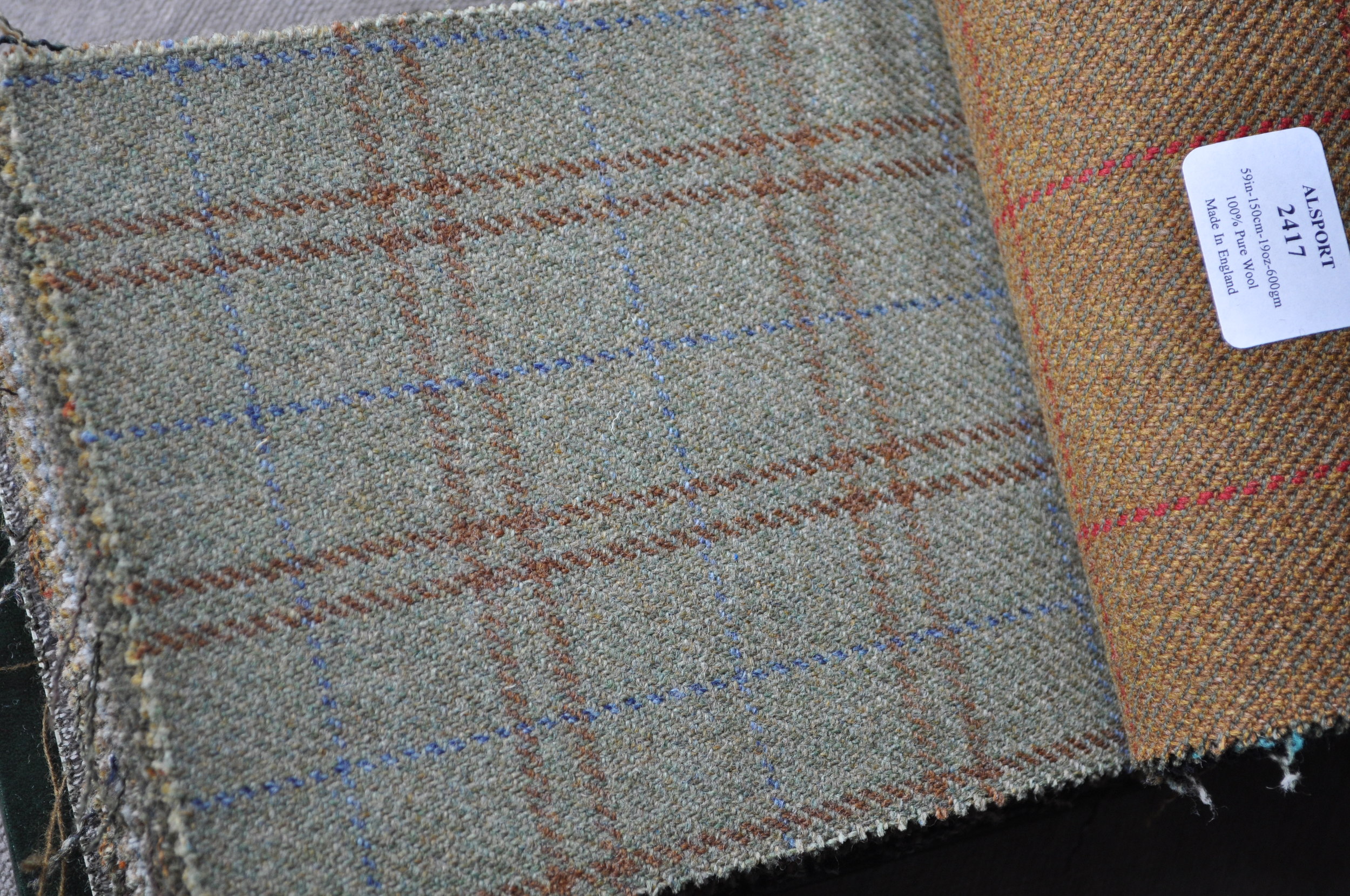

So what makes a good candidate? A whispy navy blazer? Crisp linen in cream? A rumpled madras, as unserious as it is unstructured? I’m inclined to say a single jacket won’t, in the long term, suffice. But I wonder if, in a garment category predicated upon compromise, an amalgamation of the above examples is not possible. The most promising cloth for the job that I have encountered draws the desirable characteristics of several fibers into a blend, creating something greater than its parts. Wool gives body and resilience; linen, coolness and texture; silk, luster and durability. All the big cloth makers and merchants offer cloth in varying mixtures, and I have often seen ready-to-wear jackets in similar compositions.

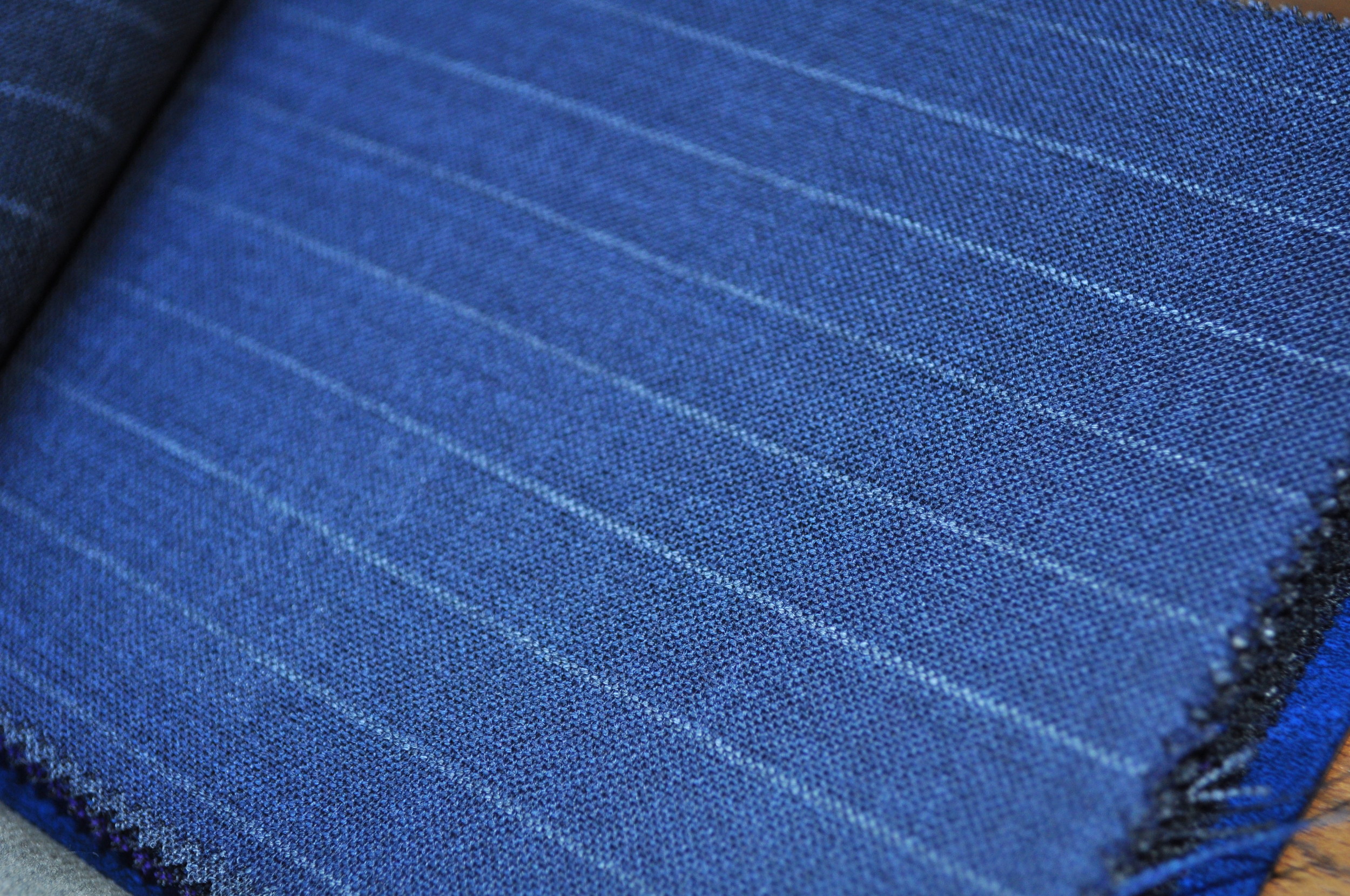

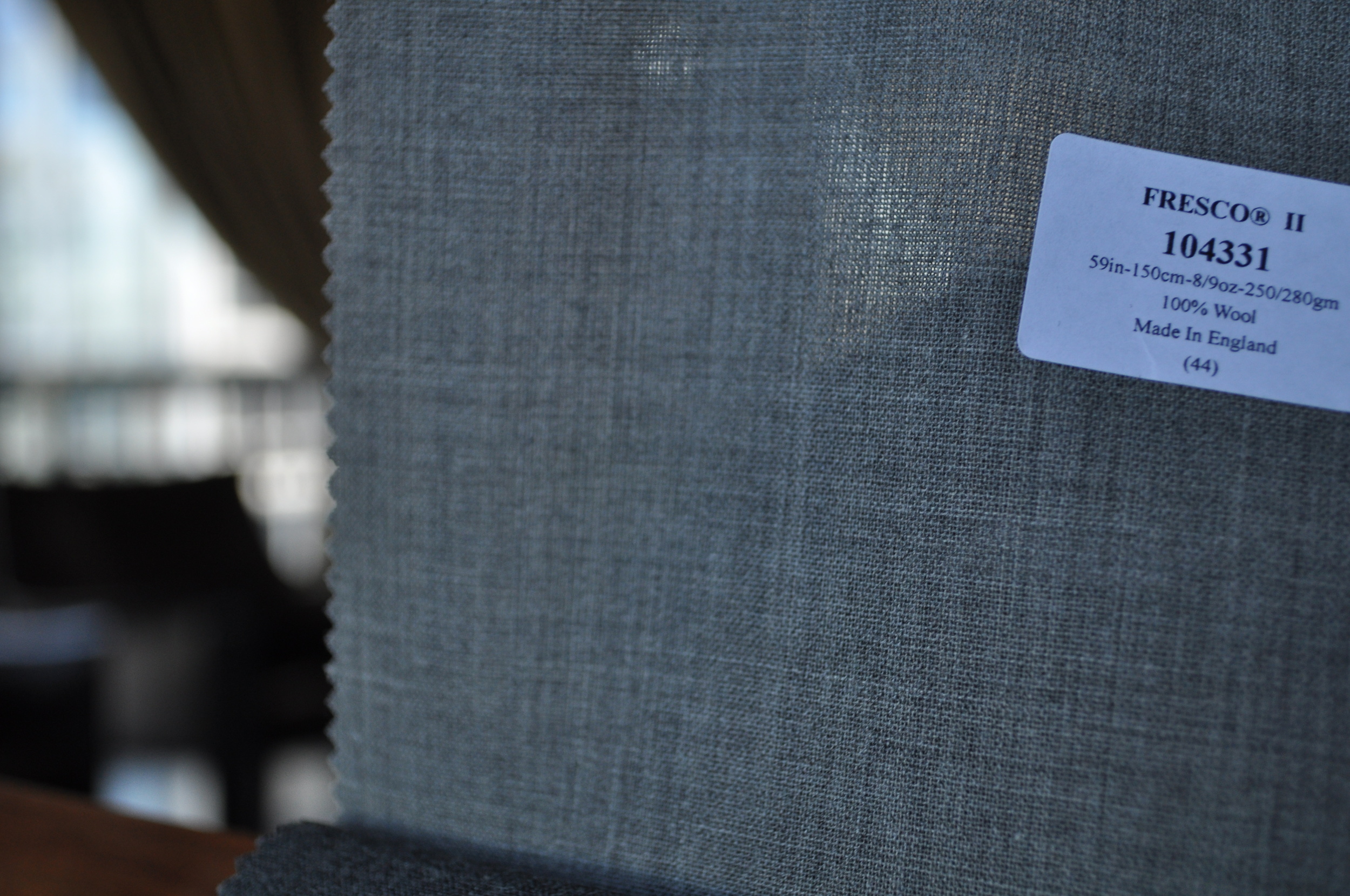

But another possibility lurks—lightweight worsted merino, which, through the miracle of modern weaving technology, achieves resistance to wrinkles, breathability and durability despite its weight. I can almost hear the collective arching of eyebrows as I suggest modern worsteds on these pages as I have always preferred more traditional and heavier cloths. But so goes innovation (when done well), and I would hardly be alone amongst other lovers of heavy cloth in admiring the handle of these lightweight wonders. In a variegated navy, perhaps with a modest shadow pattern and bone-colored buttons, a summer odd jacket might not seem so odd after all.