Taking Stock

Anthropologists might describe my restlessness as a stifled urge to prepare for harvest and winter. The industrious ant at ethical odds with the singing grasshopper, etc. I blame the dying cicadas. Or the calvados at lunch. Either way, these undecided weeks between summer and the cooler seasons ahead always nudge me into reflection and, eventually, action. I beat carpets and rearrange furniture. I turn a melancholic eye to the garden; should I provide a quick and compassionate end for my flagging annuals? Wood is split and things get painted.

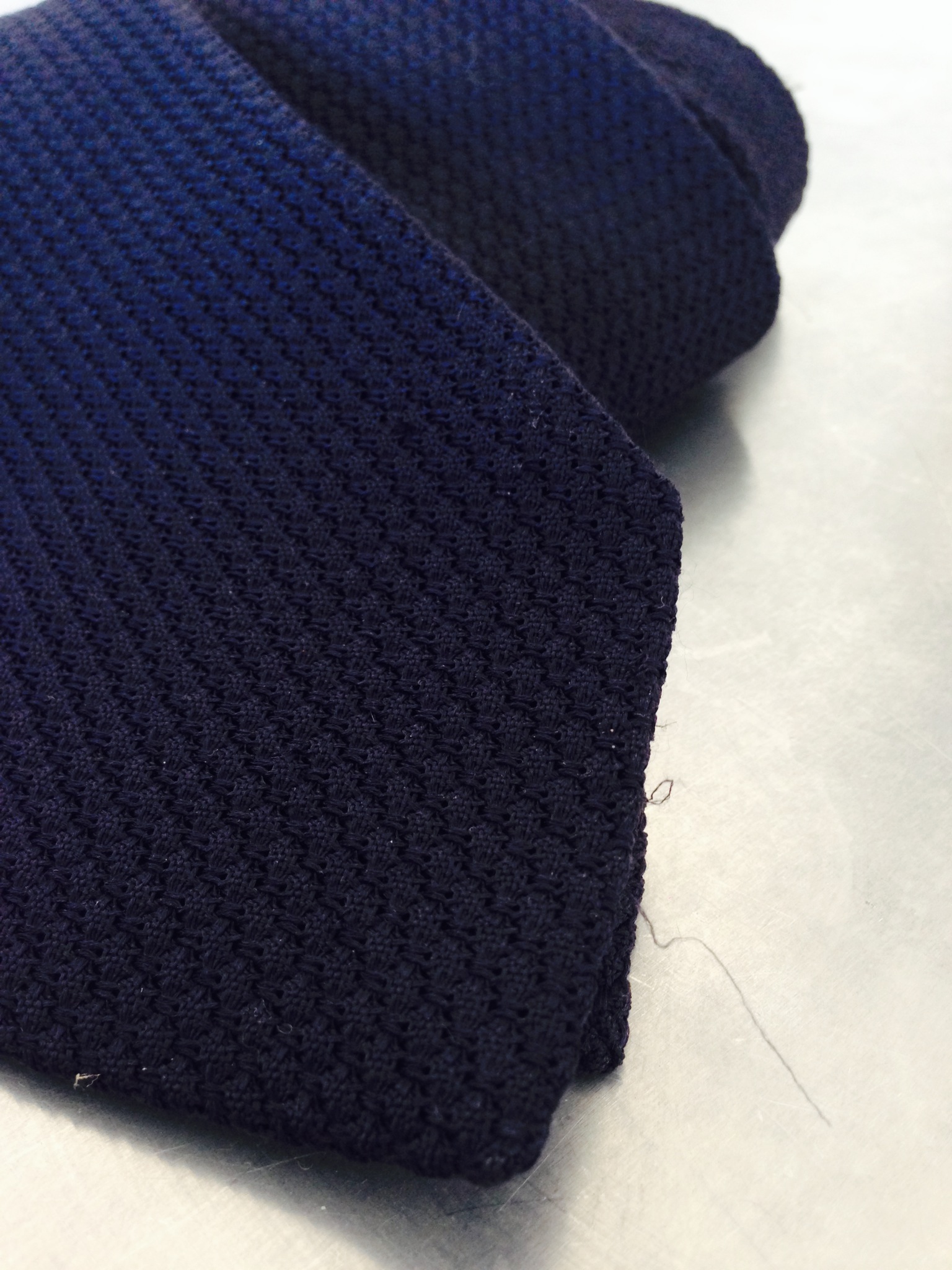

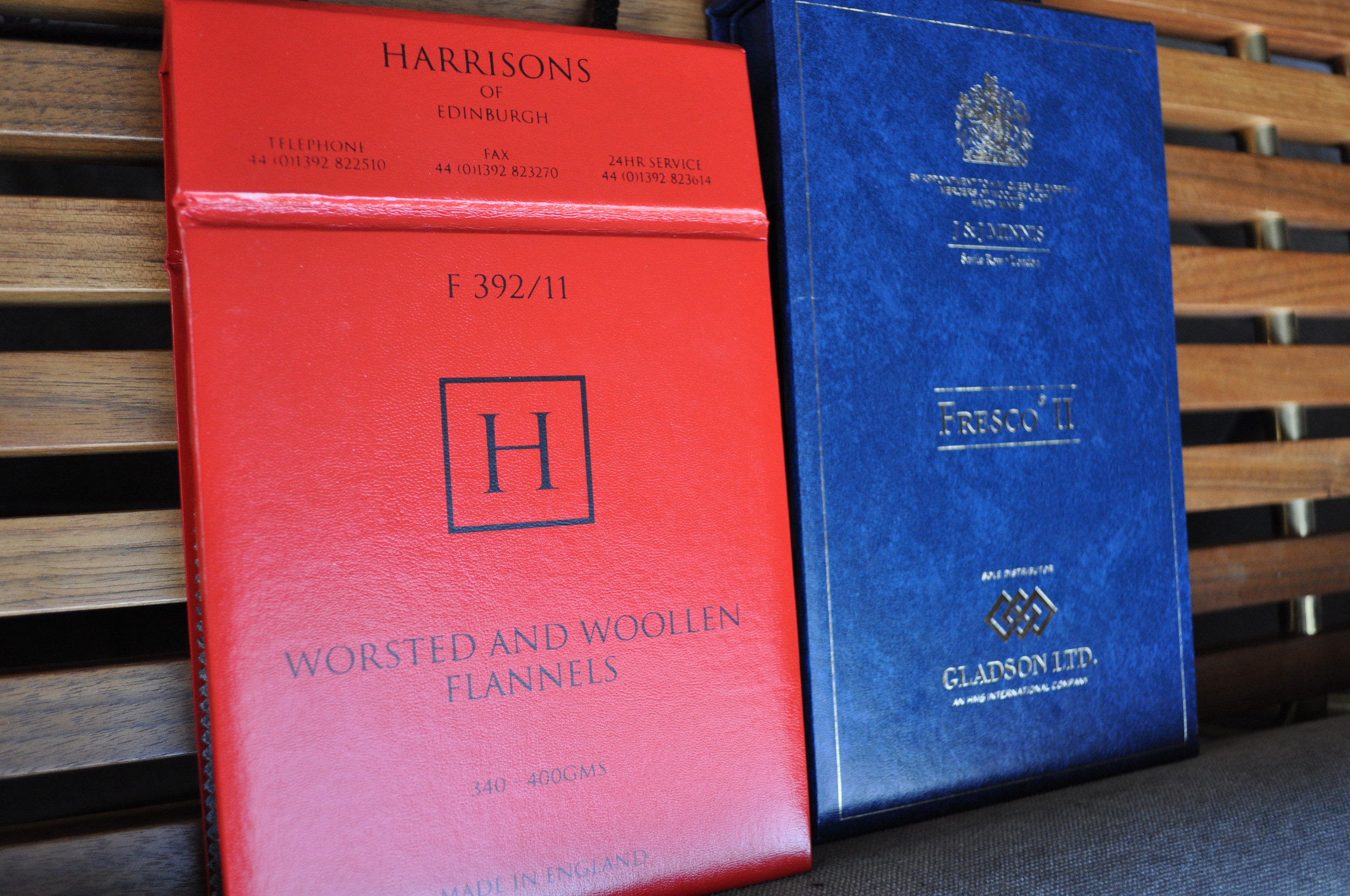

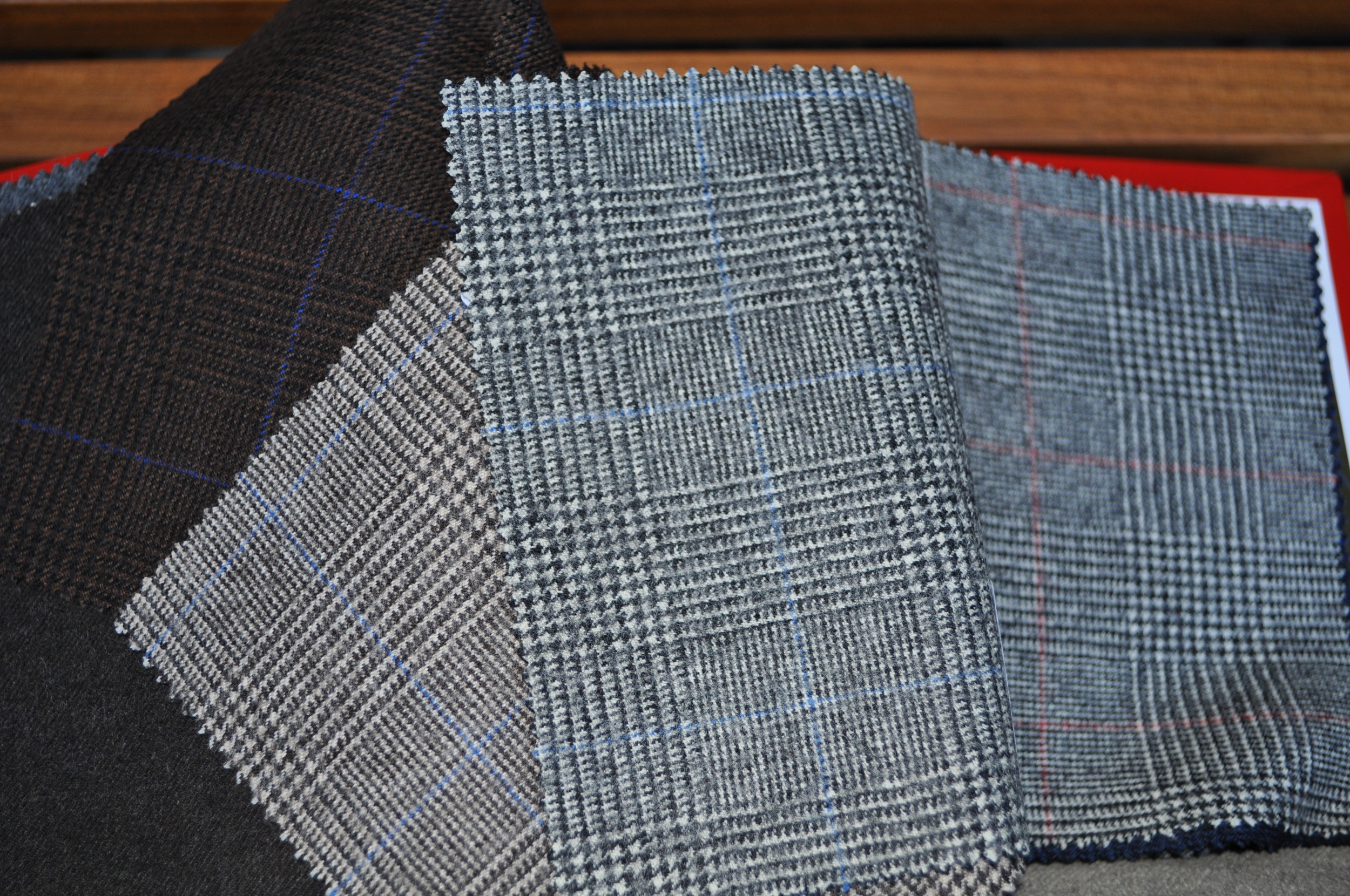

When attention falls to clothing and accessories, however, a gentler touch is required. Consider the collar: what is the invisible threshold between charming fraying and the need to have a new one made? Maybe it is time to replace the warped scales of an old straight-razor, or give up on an ancient crocodile belt whose own scales hang perilously. Old boots are always evocative. But mink oil and elbow grease must be used judiciously—too heavy a hand can dull their beauty.

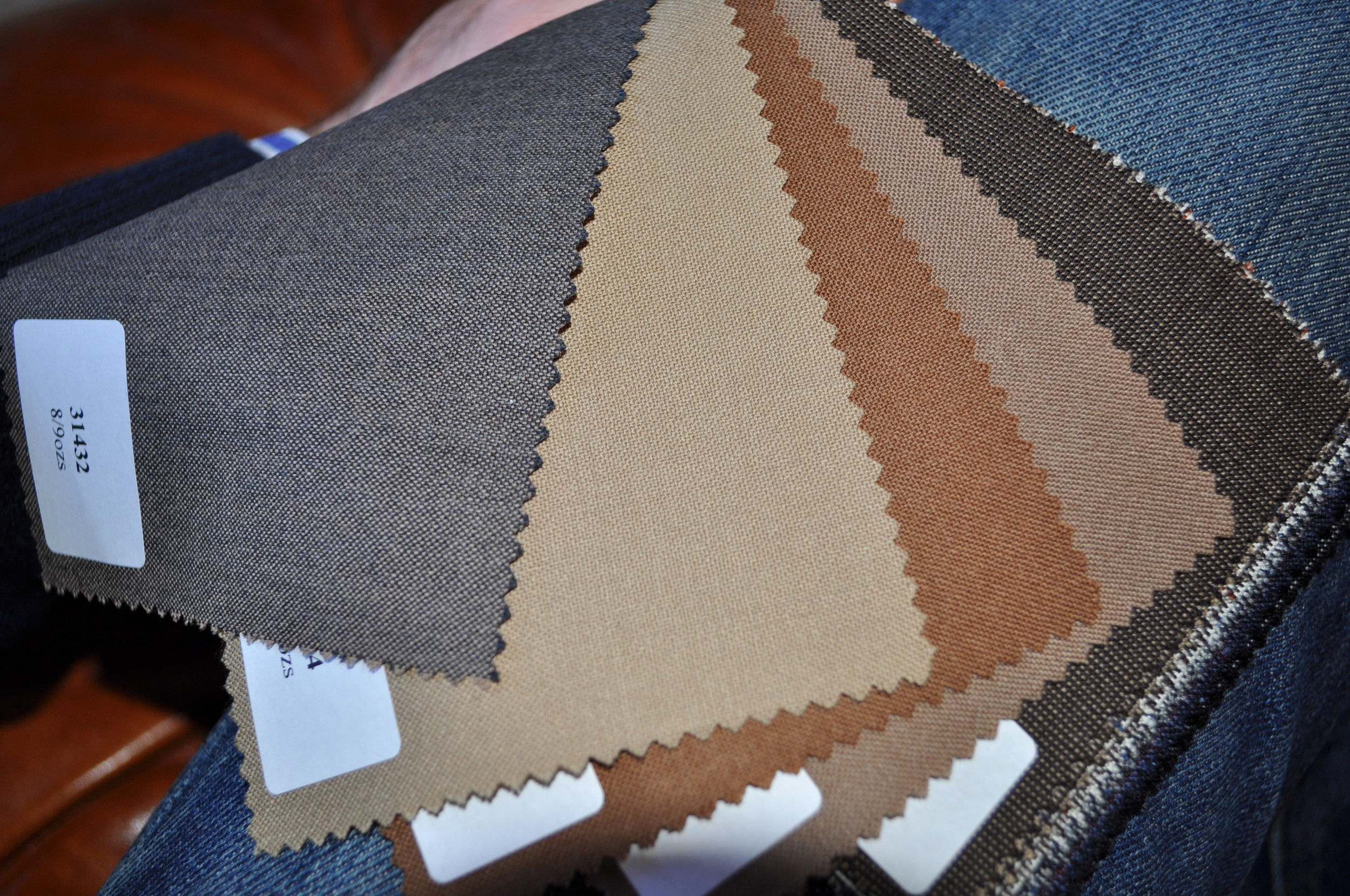

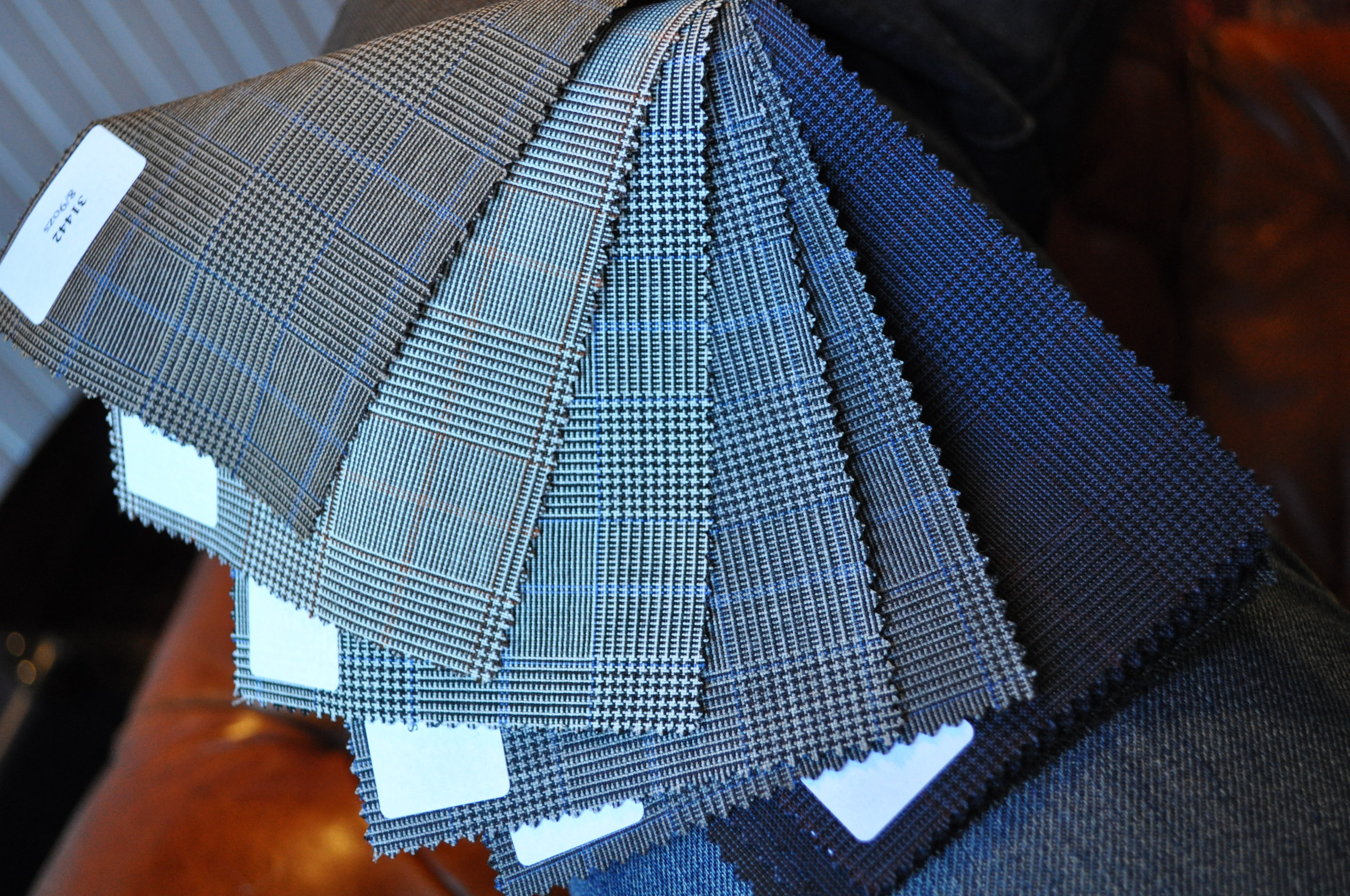

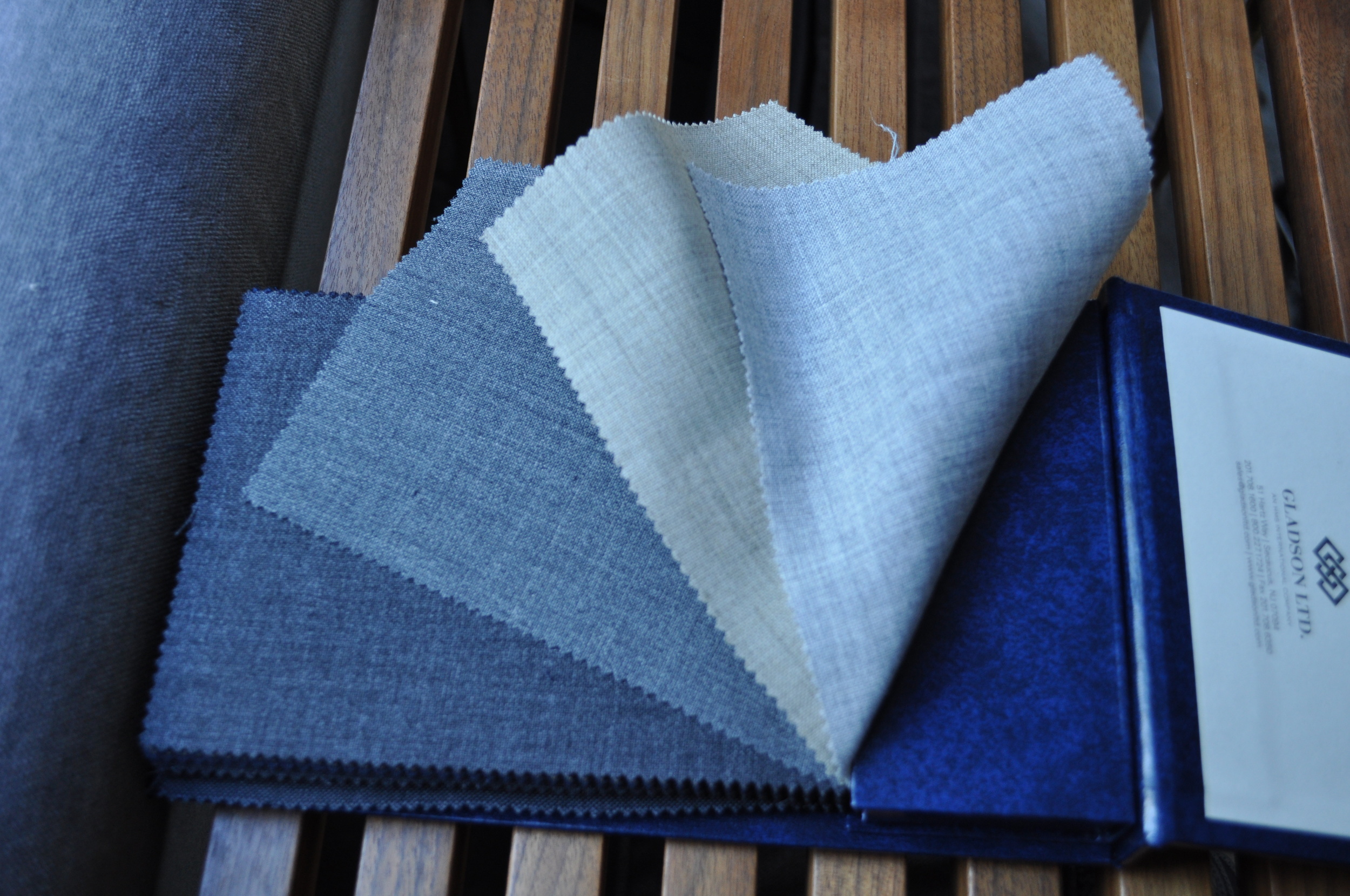

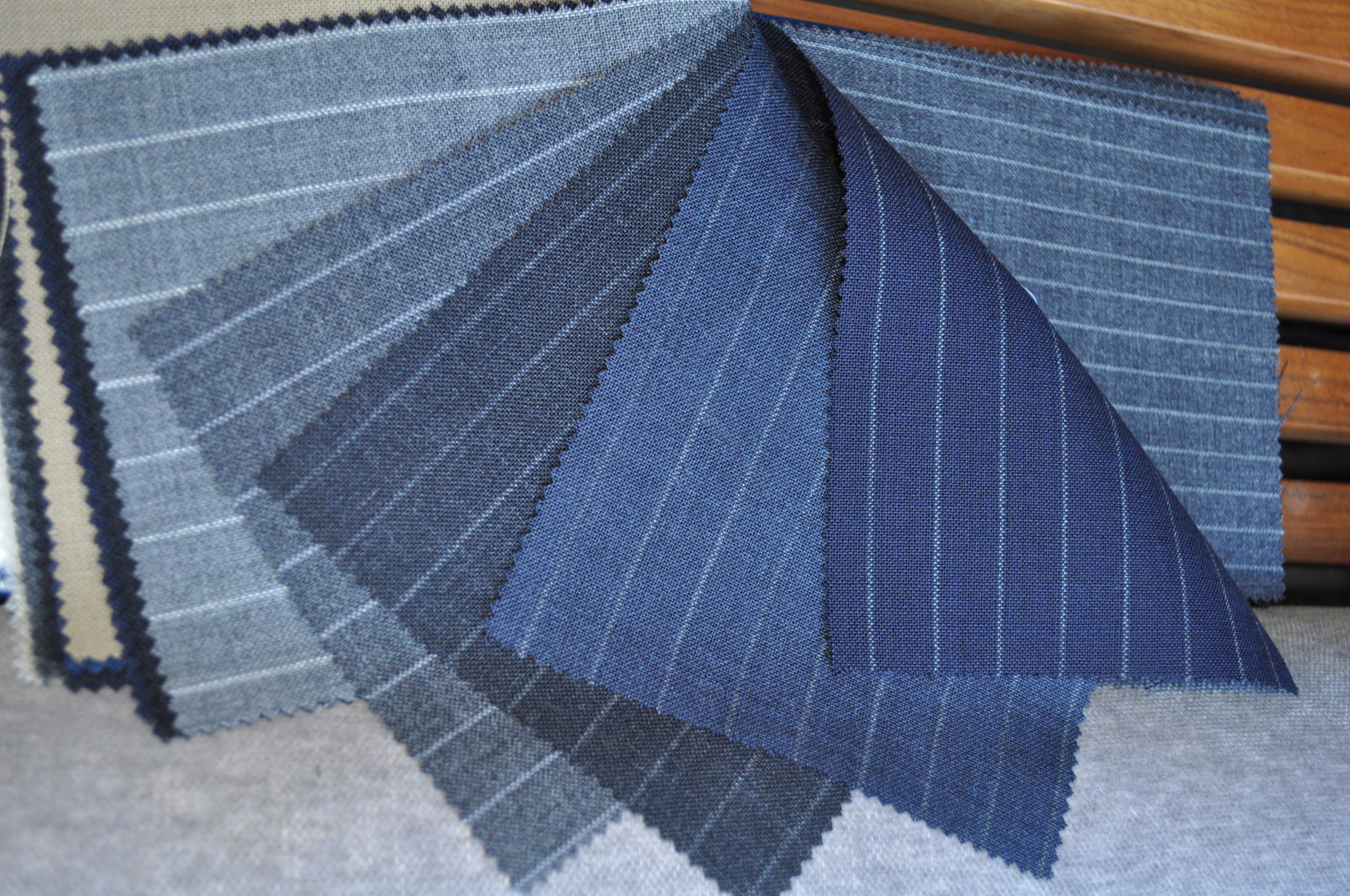

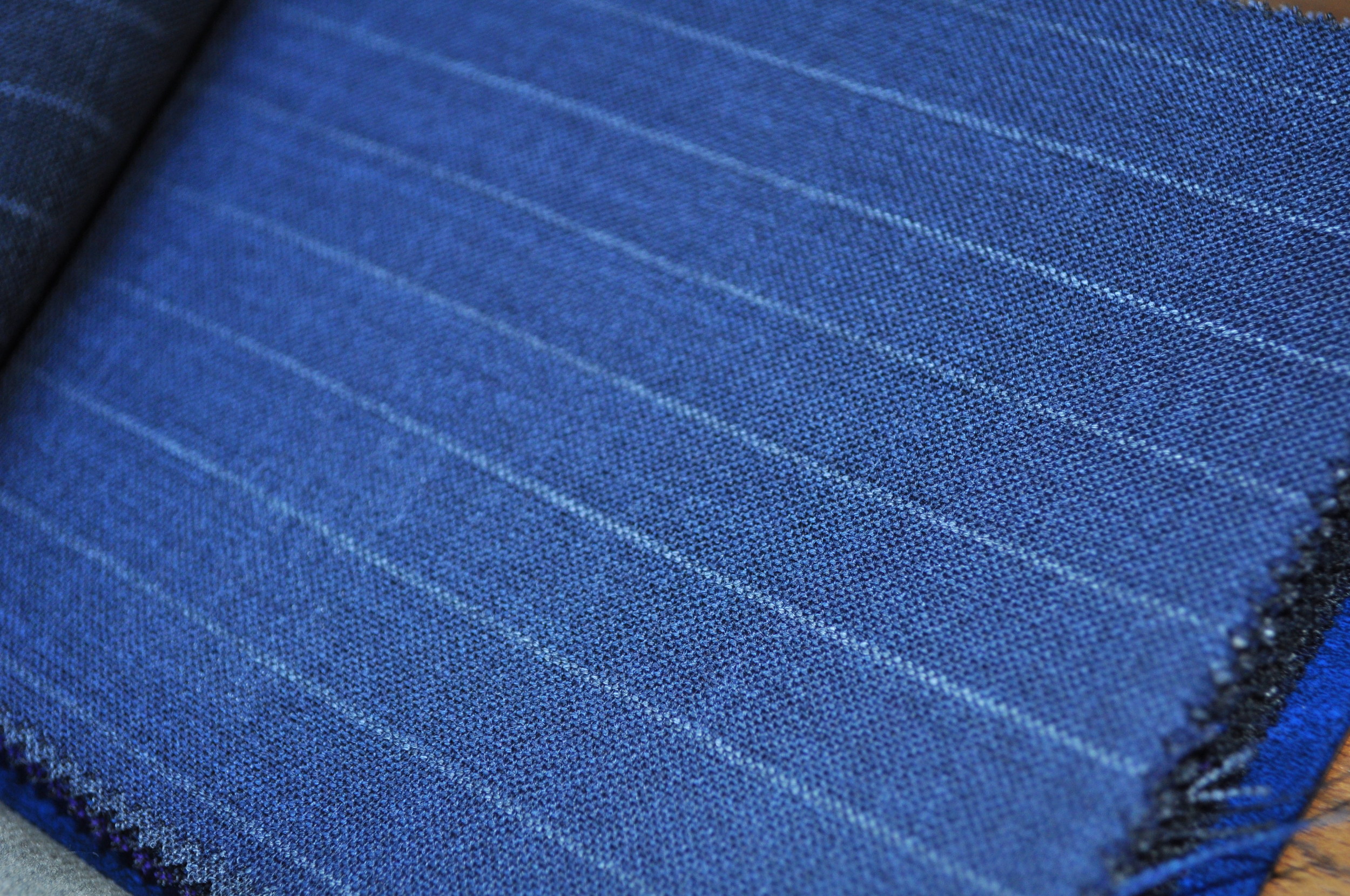

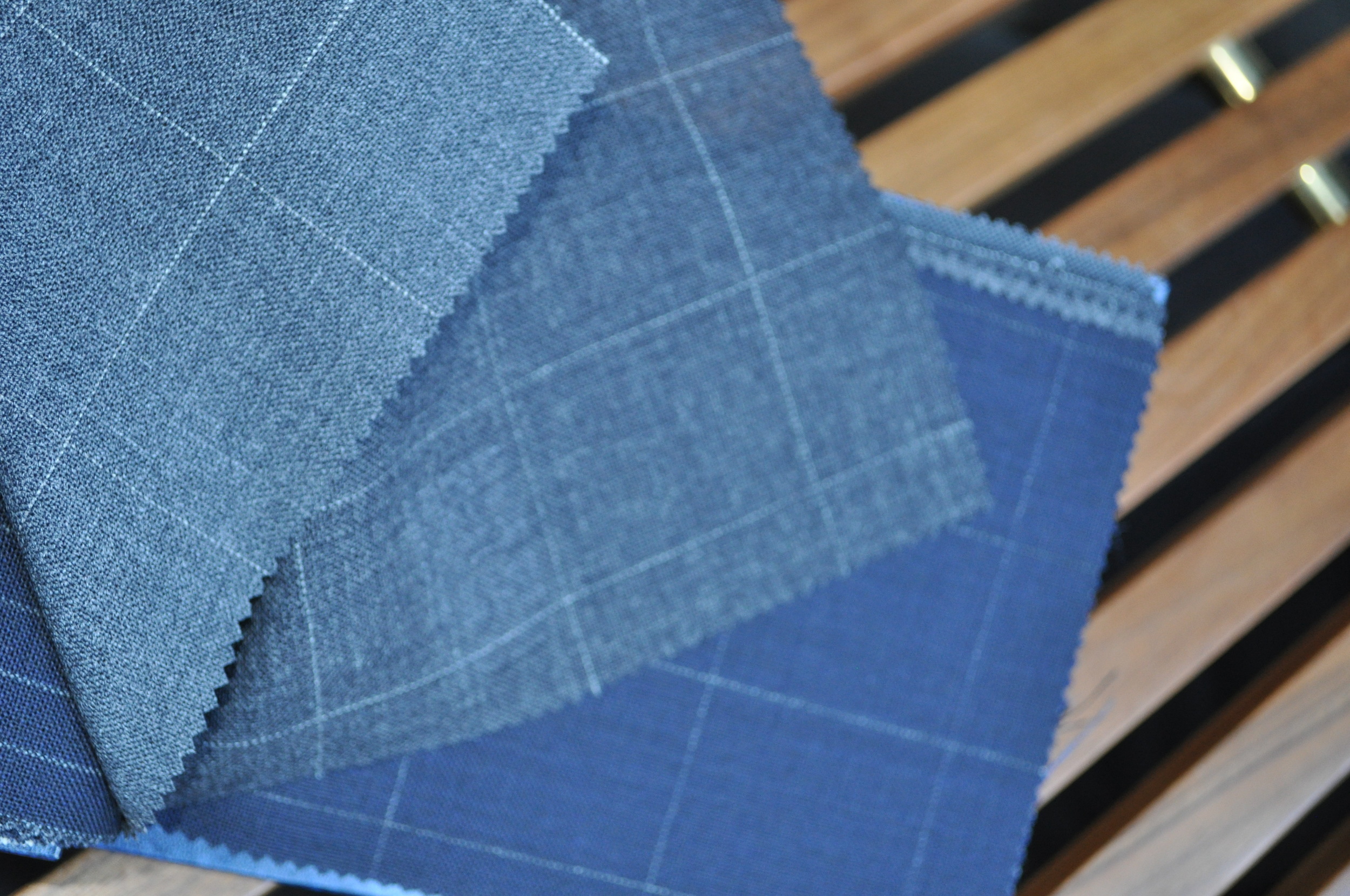

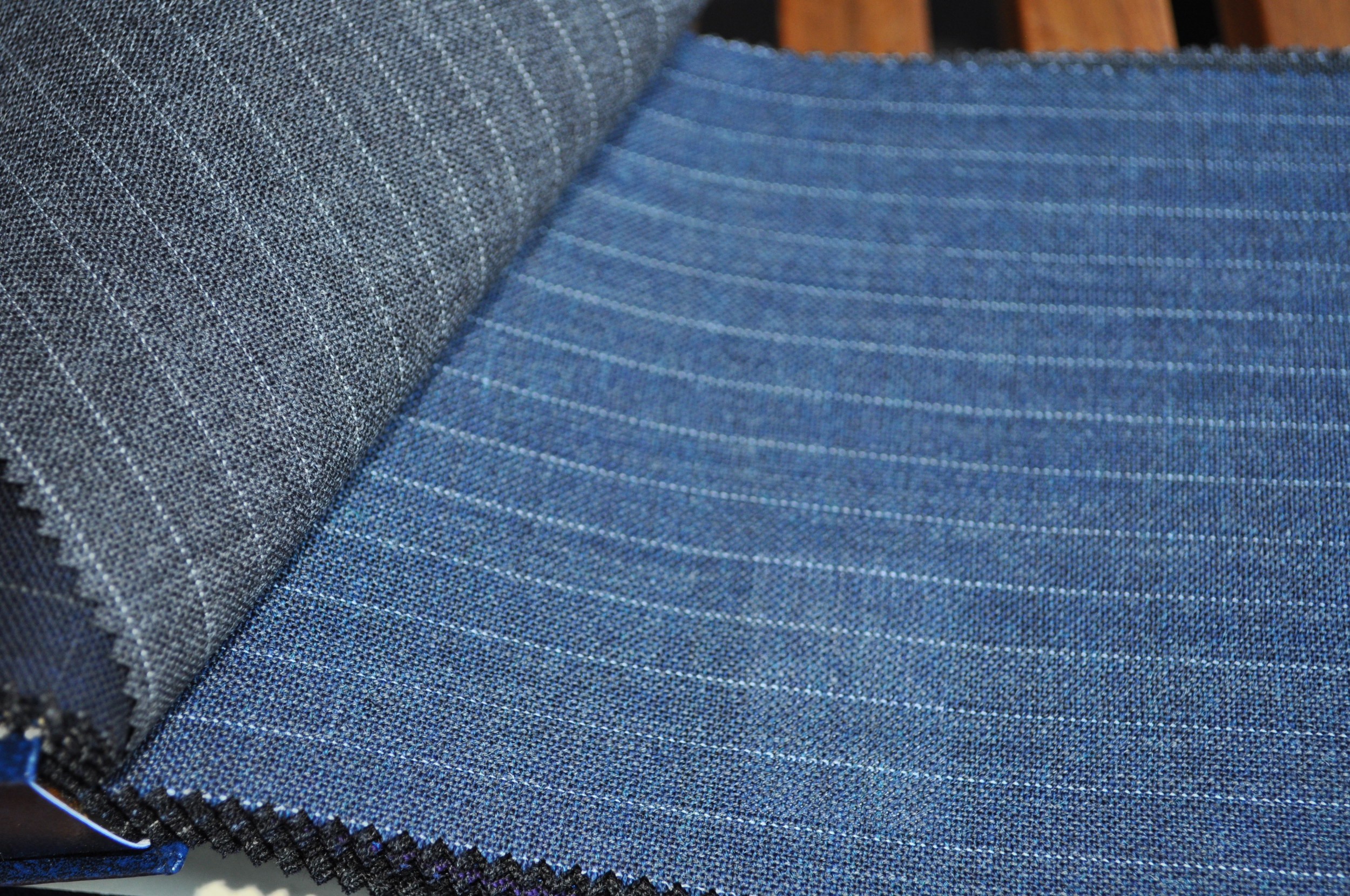

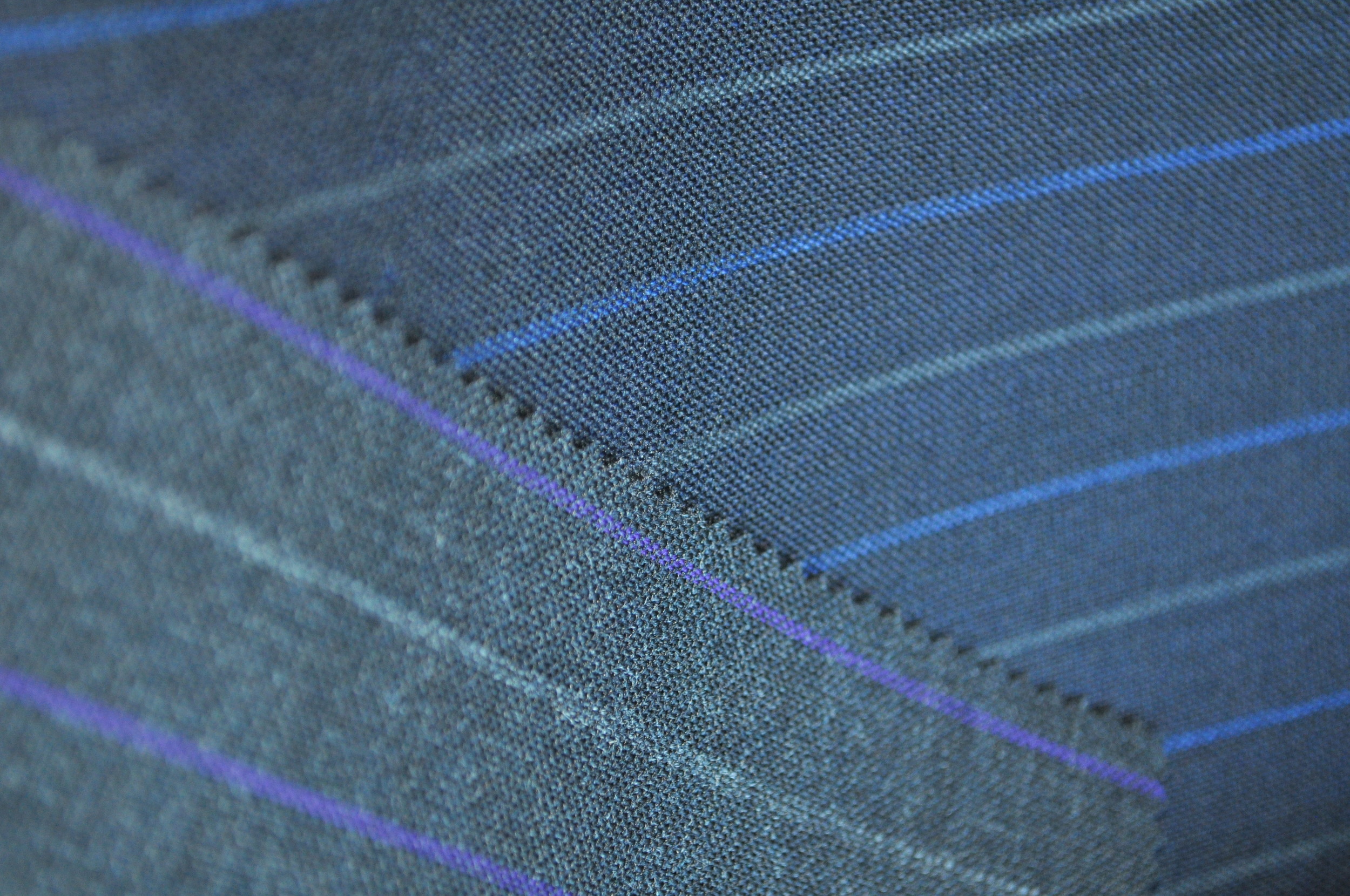

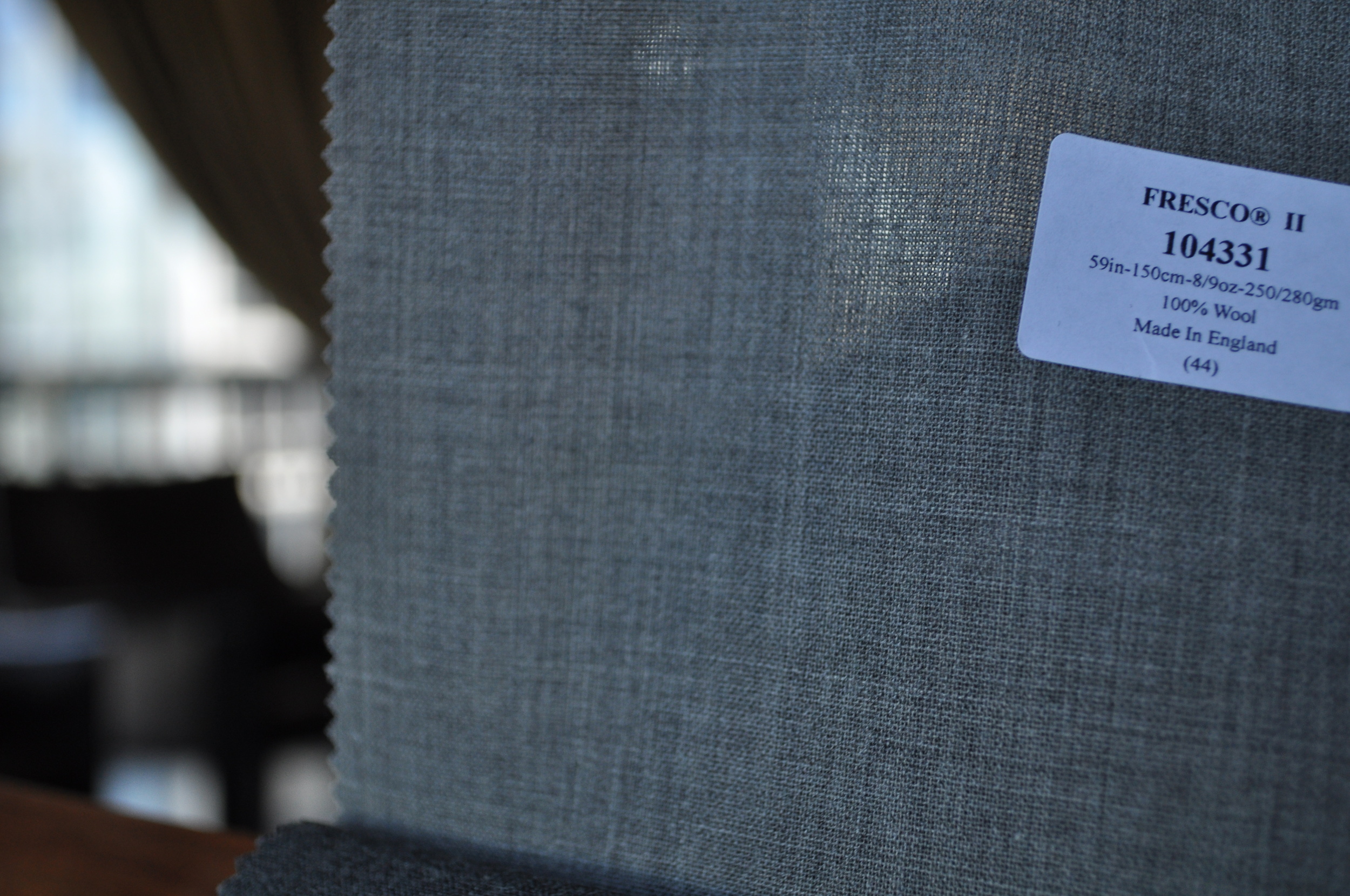

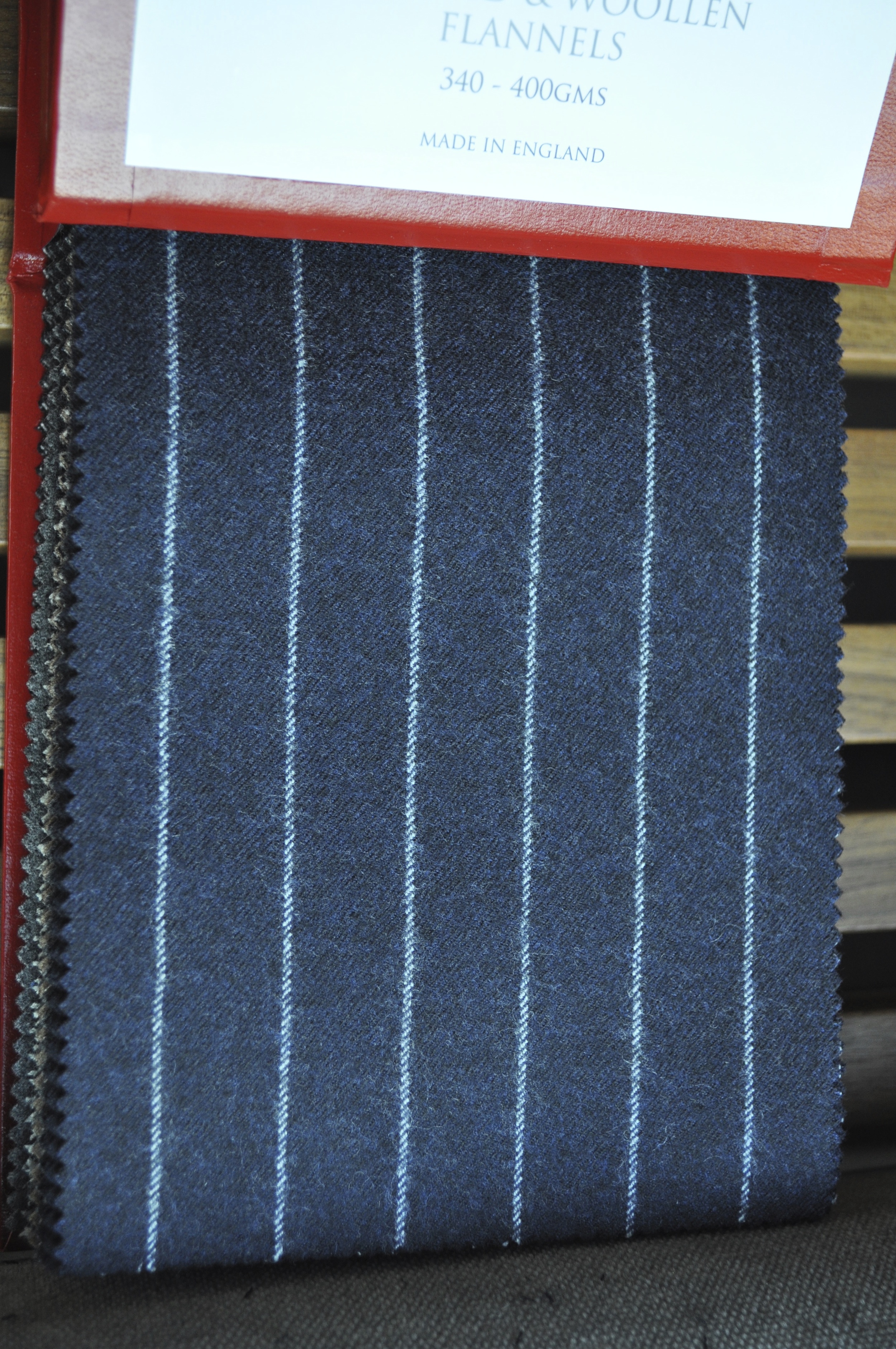

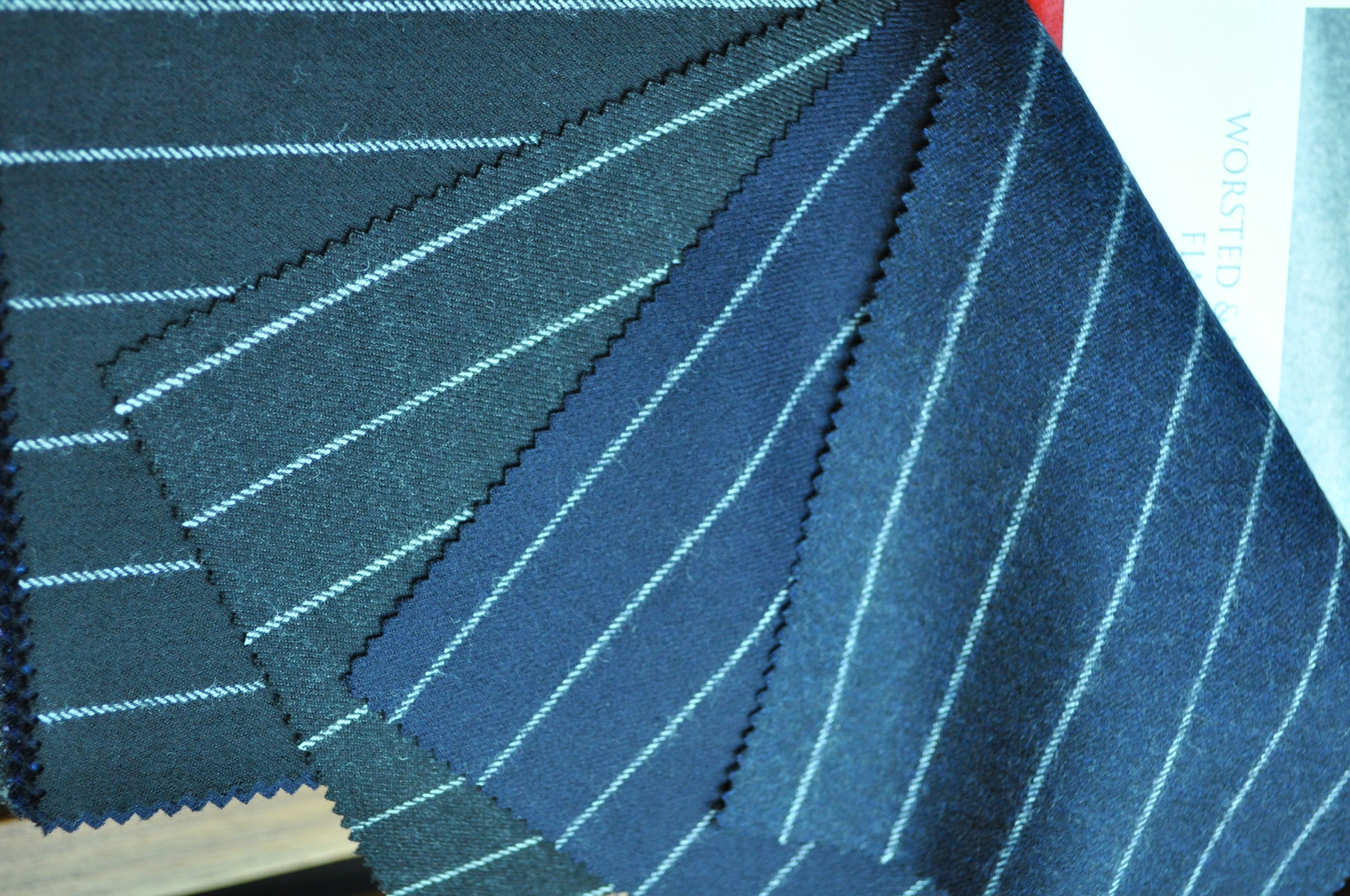

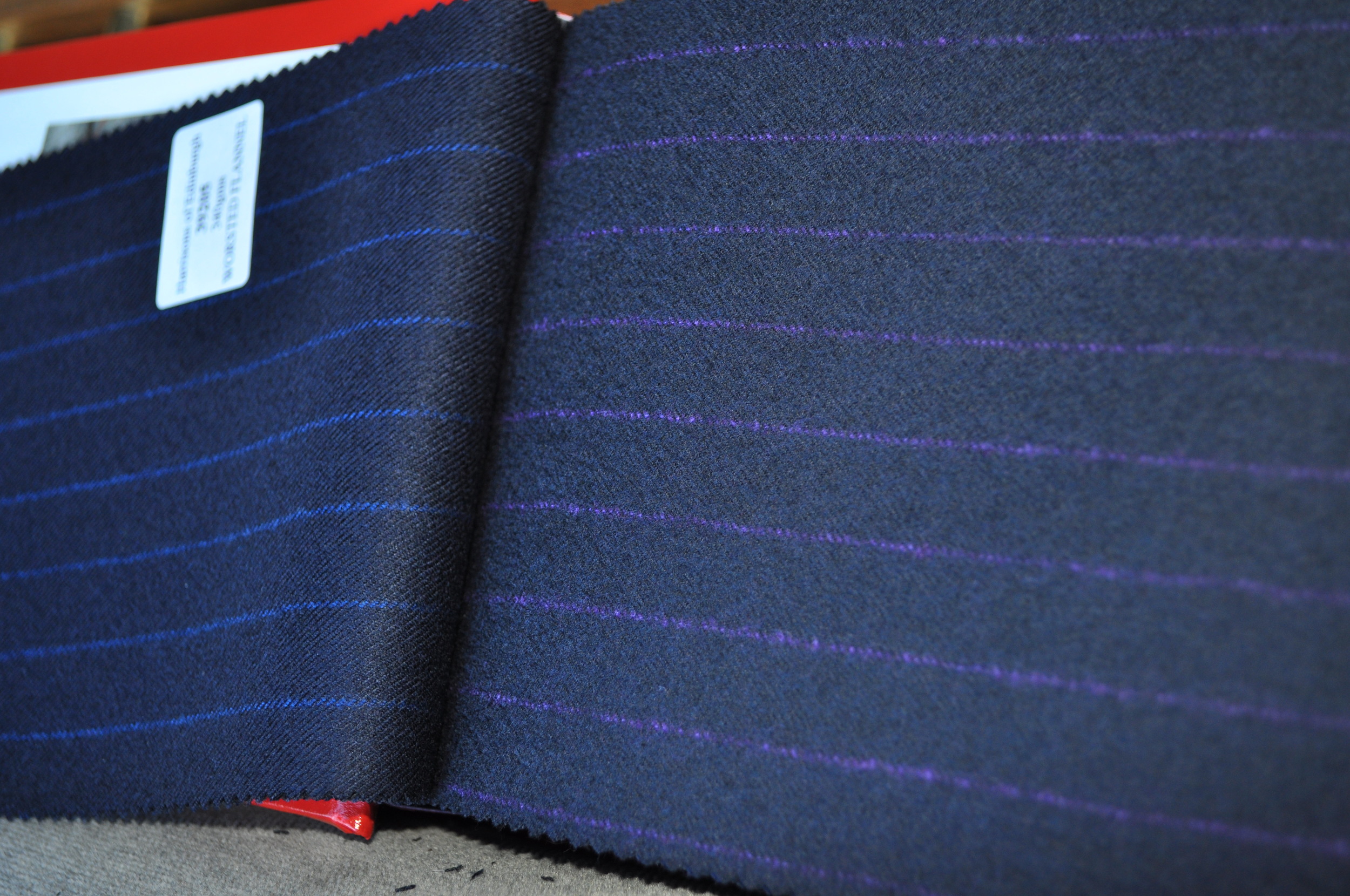

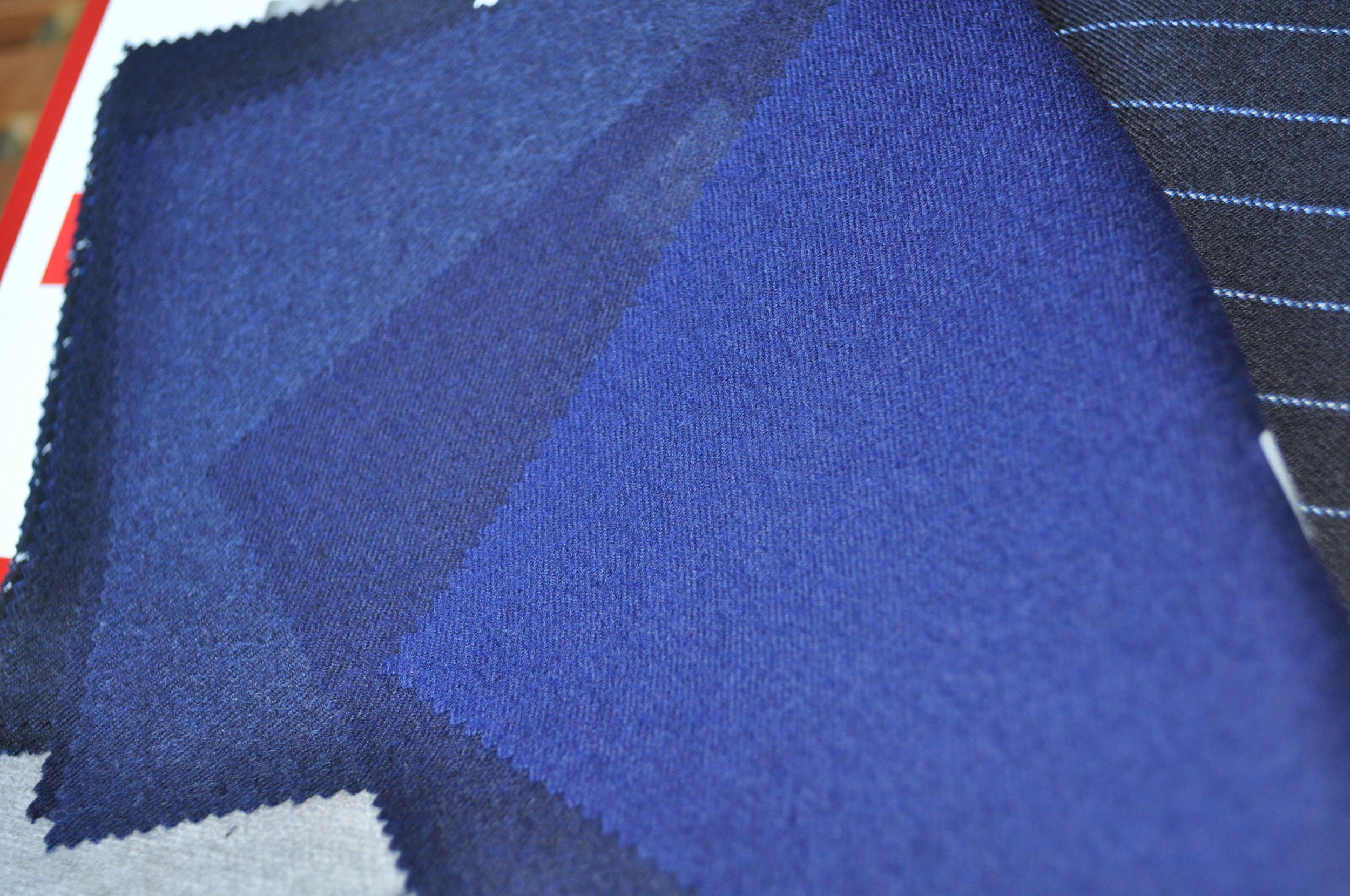

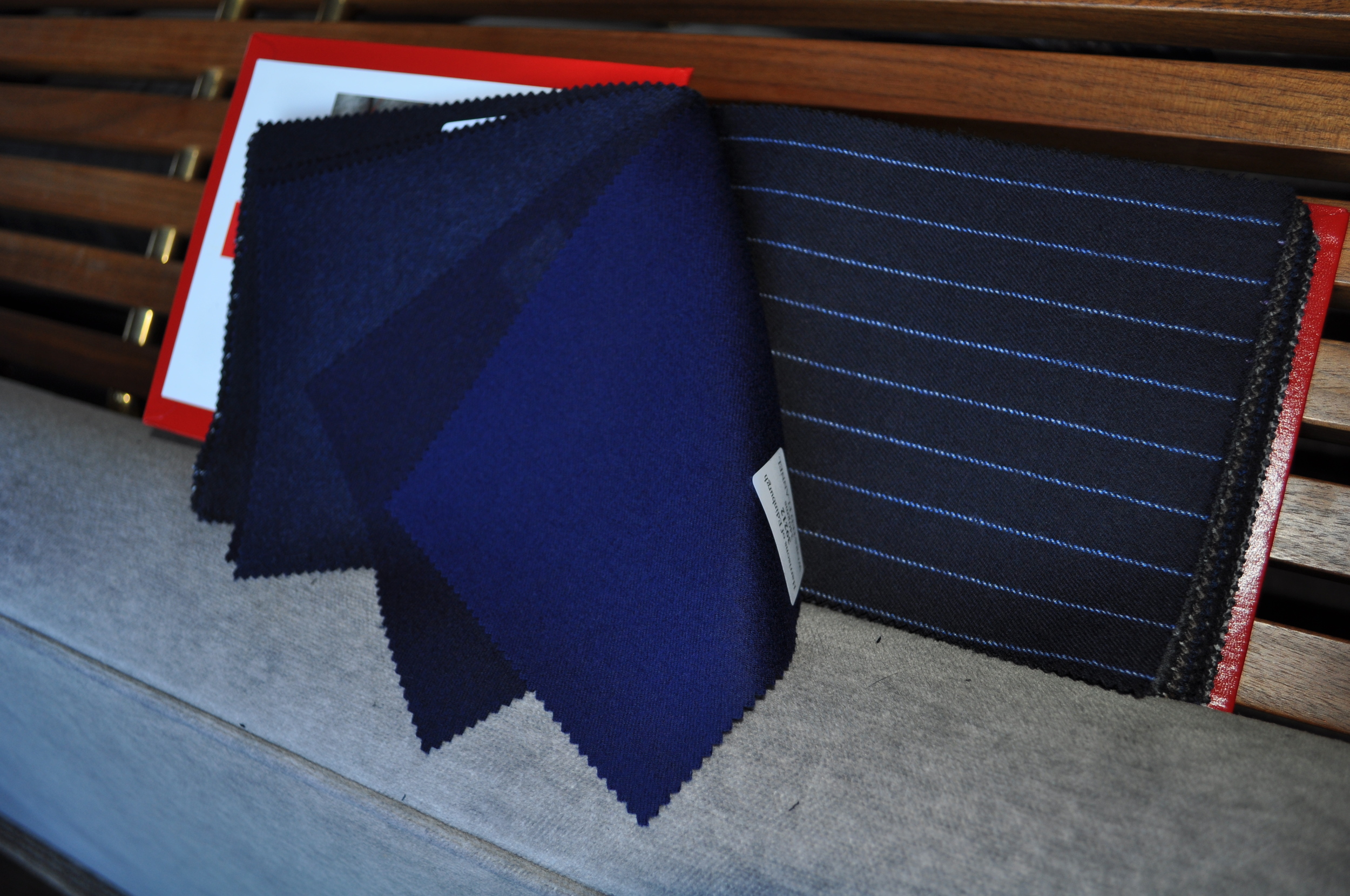

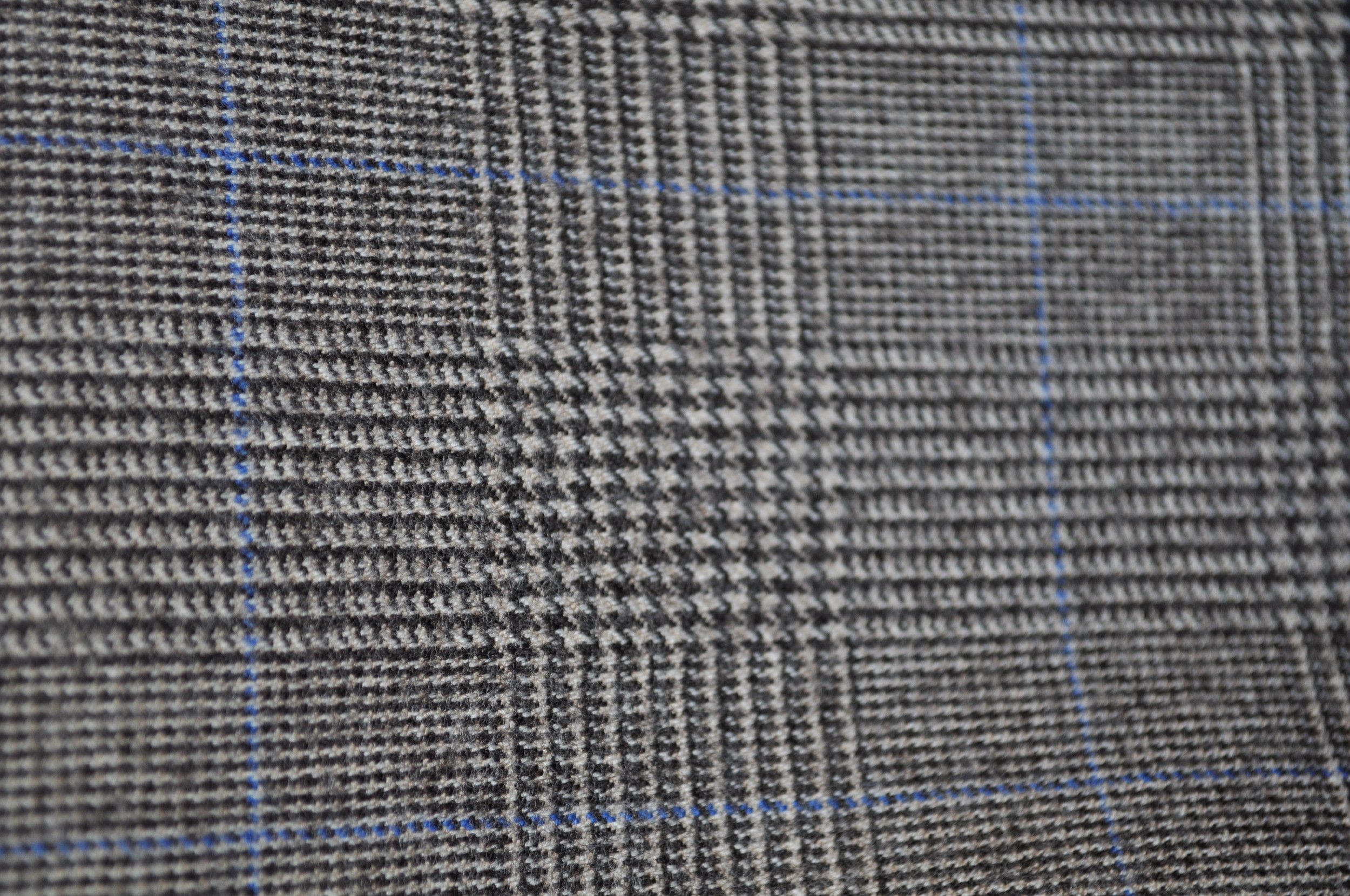

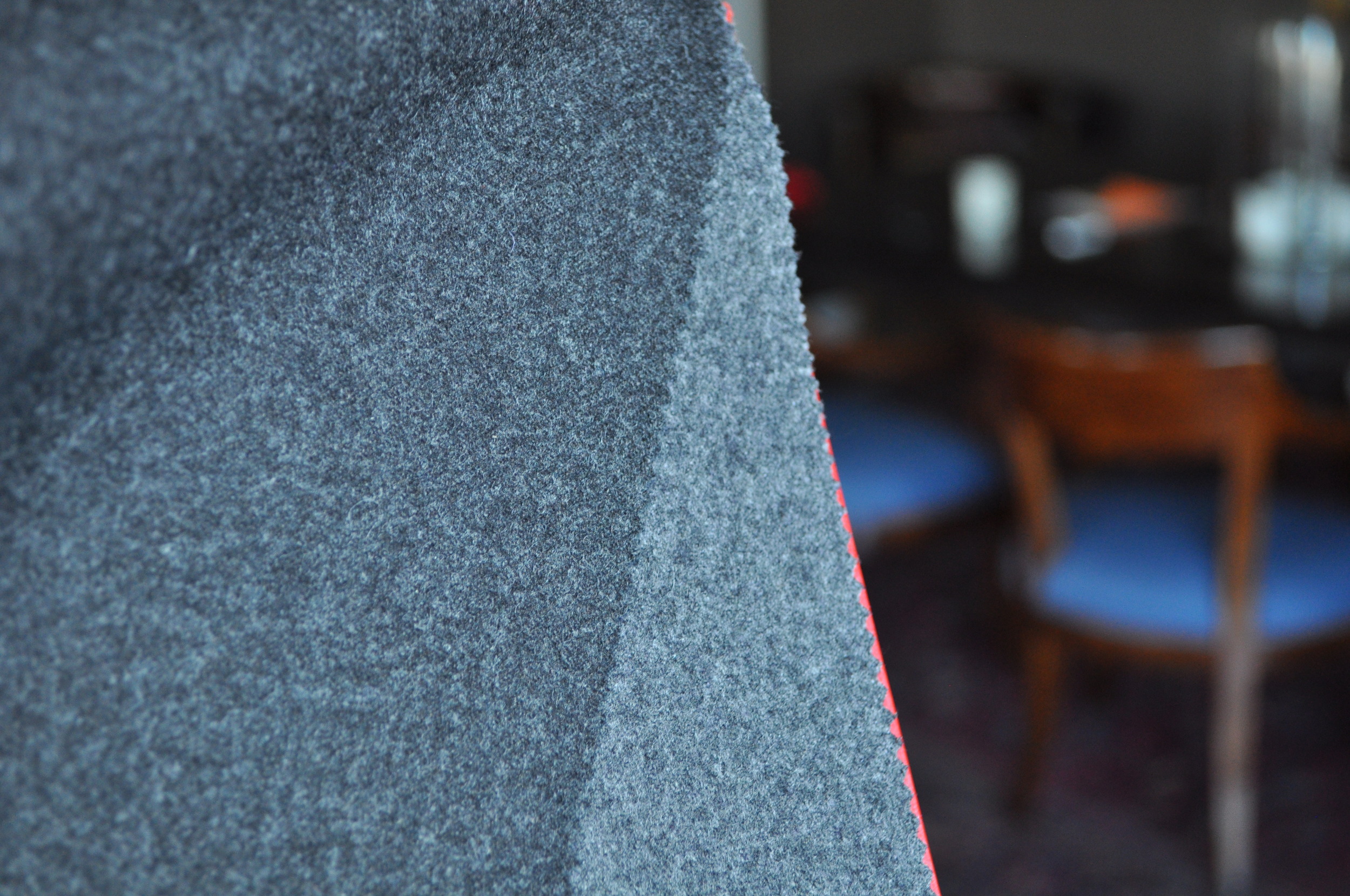

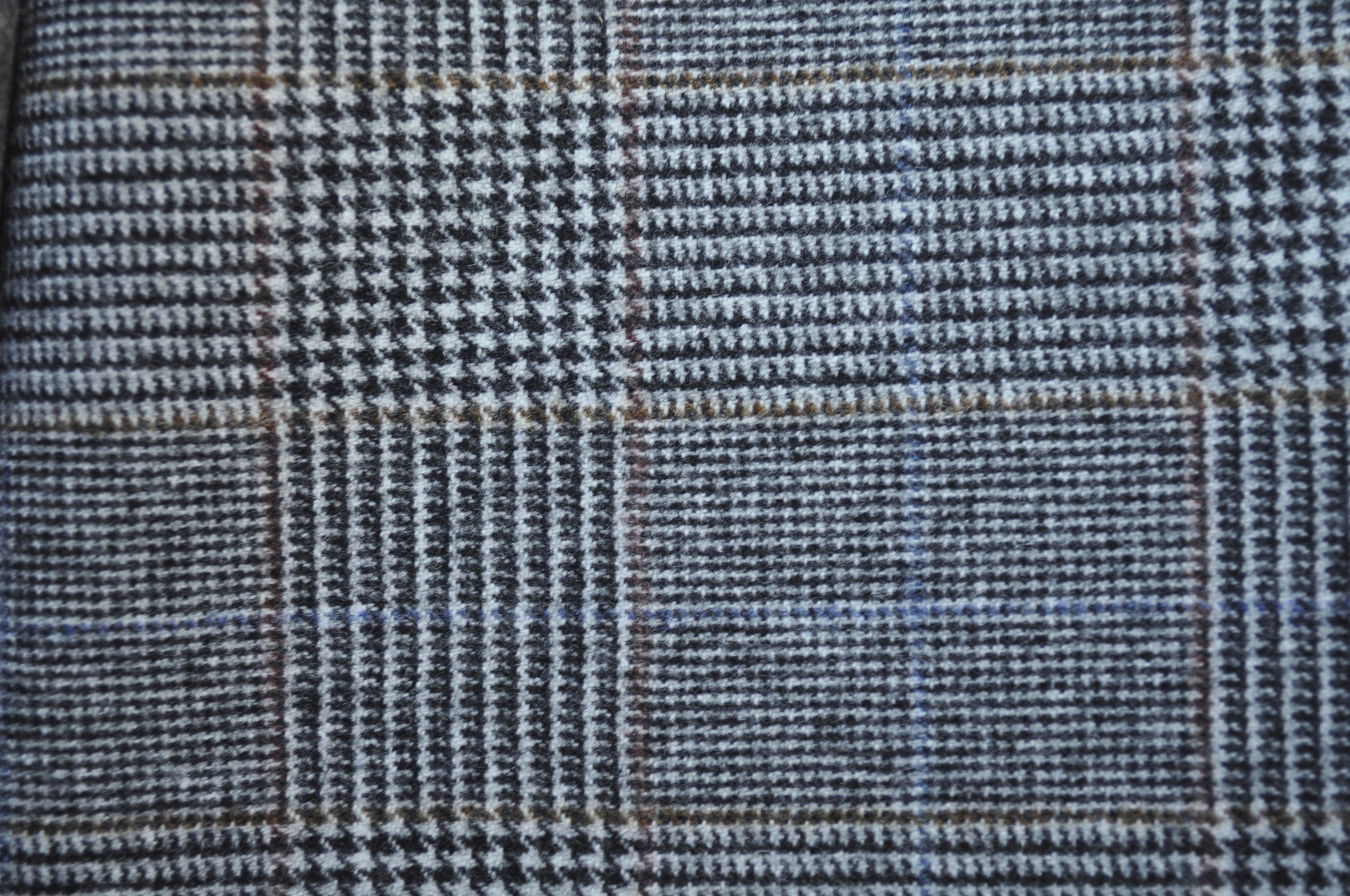

What about the intangible evidence of age? Jackets with canvass chests mold to the figure. Shoulders in stout tweed don’t so much collapse as they do settle. Worsteds indescribably soften and linen trades some of its famous crispness for a fuller hand. My favorite is the cotton shirt; somewhere beyond twenty launderings even ordinary cloth takes on a satisfying plushness. But these desirable effects aren’t just invisible; they are temporary. A soft and full hand is only the initial sign of a less welcome realization—that of decay. But I’m not the first to consider the tension between labor and the inevitability of deterioration. Robert Frost managed a few excellent lines on the topic:

…I thought that only

Someone who lived in turning to fresh tasks

Could so forget his handiwork on which

He spent himself, the labour of his axe,

And leave it there far from a useful fireplace

To warm the frozen swamp as best it could

With the slow smokeless burning of decay. (34-40,The Wood-Pile,1912)