Craft Project

Raw denim jeans, stiff enough to lean against a door unassisted. Wearing them in at this stage is crucial. And torturous.

Plenty of style writers (and even proper writers) hotly defend or persecute jeans. Though I wear fairly classic clothing in fashion-resistant cuts, I come down firmly in defense of jeans as a sort of current day buckskin trouser—just the thing for casual and active occasions. They do have one very significant downside though: for a casual garment jeans are awfully high-maintenance.

This struck upon me one day when I was at a friend’s house for cocktails. I opened his freezer, and instead of ice cubes for my Tom Collins I found three pairs of jeans stacked neatly between the Russian vodka and frozen pigs-in-a-blanket. I had only before that day heard of the practice of freezing worn jeans to kill off the bacteria that causes odor; having witnessed it I decided I would never permit myself to own anything with so dialed-in a fit as to not tolerate conventional laundering.

Although my routine for jeans is hardly conventional. Some years ago, dissatisfied with the pre-weathered washes and special effects dominating the jeans market, I was ushered toward raw denim by a helpful salesperson. He must have known that I would respond to the do-it-yourself approach these jeans required, as rather than giving the heritage pitch he went strait for the clinch: you should get two pairs in case you mess one up. Remarkably, these were also the cheapest jeans in the place as all the artful faux finishes add significantly to the cost of manufacturing. This is perhaps the only opportunity one will ever have to pay less for more control over a garment.

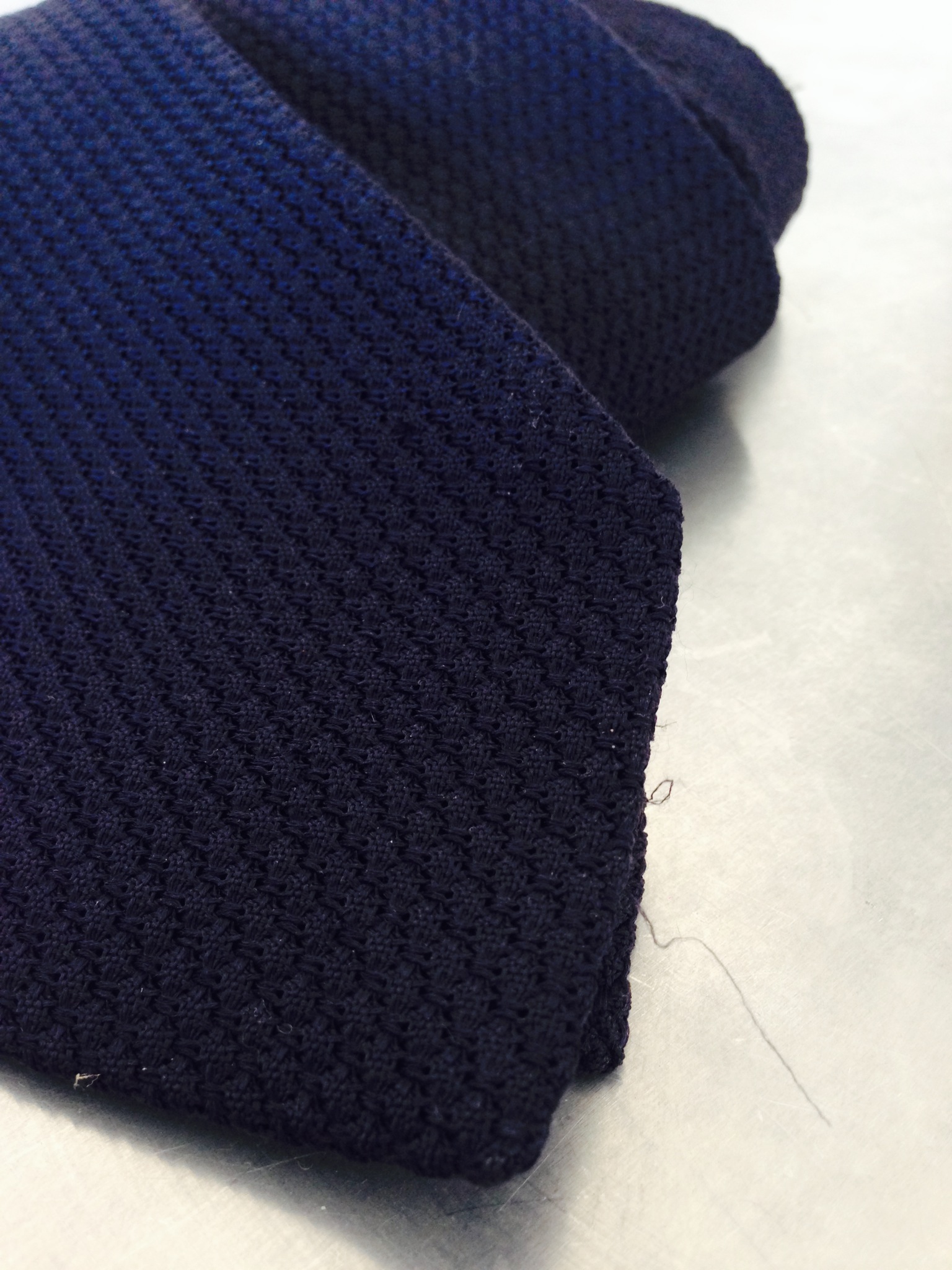

True raw denim is a stiff cotton twill over-dyed with natural indigo. Cotton is hydrophilic (meaning it absorbs water) and so raw denim will shrink as the cotton fibers dry out and contract. Some raw denim has already been soaked and slowly dried, known as sanforized, so the consumer won’t have to contend with blindly guessing at size. Mine were unsanforized, meaning the denim goes from loom to cutting and sewing room to store shelf where they reside in all their inky blue stiffness waiting to be worn. Unsanforized jeans are often referred to as shrink-to-fit, but a better term might be guess-at-fit. Most raw denim will shrink ten or fifteen percent before the fit is correct. The process is truly trial and error. Of course once the fit does seem dialed-in, the jeans will be nearing their apex, after which, decline into tatty, over-faded impossibility is inevitable.

Getting shrink-to-fit raw denim jeans to the correct size requires some thought though. The architecture of jeans is significantly different to traditional trousers. The waist, seat and side seams of standard jeans do not have inlay (additional cloth pressed flat) so proper alterations are not possible. A good alterations tailor might be able to cinch a waist or seat by cutting out a strip, but because of the contrast stitching and patch back pockets, the proportions will seem off. The better route is, with the help of a good salesperson, to try and get the fit right from the start. Once shrunken, the jeans should be snug—even tight—through the seat and thigh as they will loosen considerably through regular wear. Pay no attention to the hem—just be certain the waist, seat and thigh seems correct.

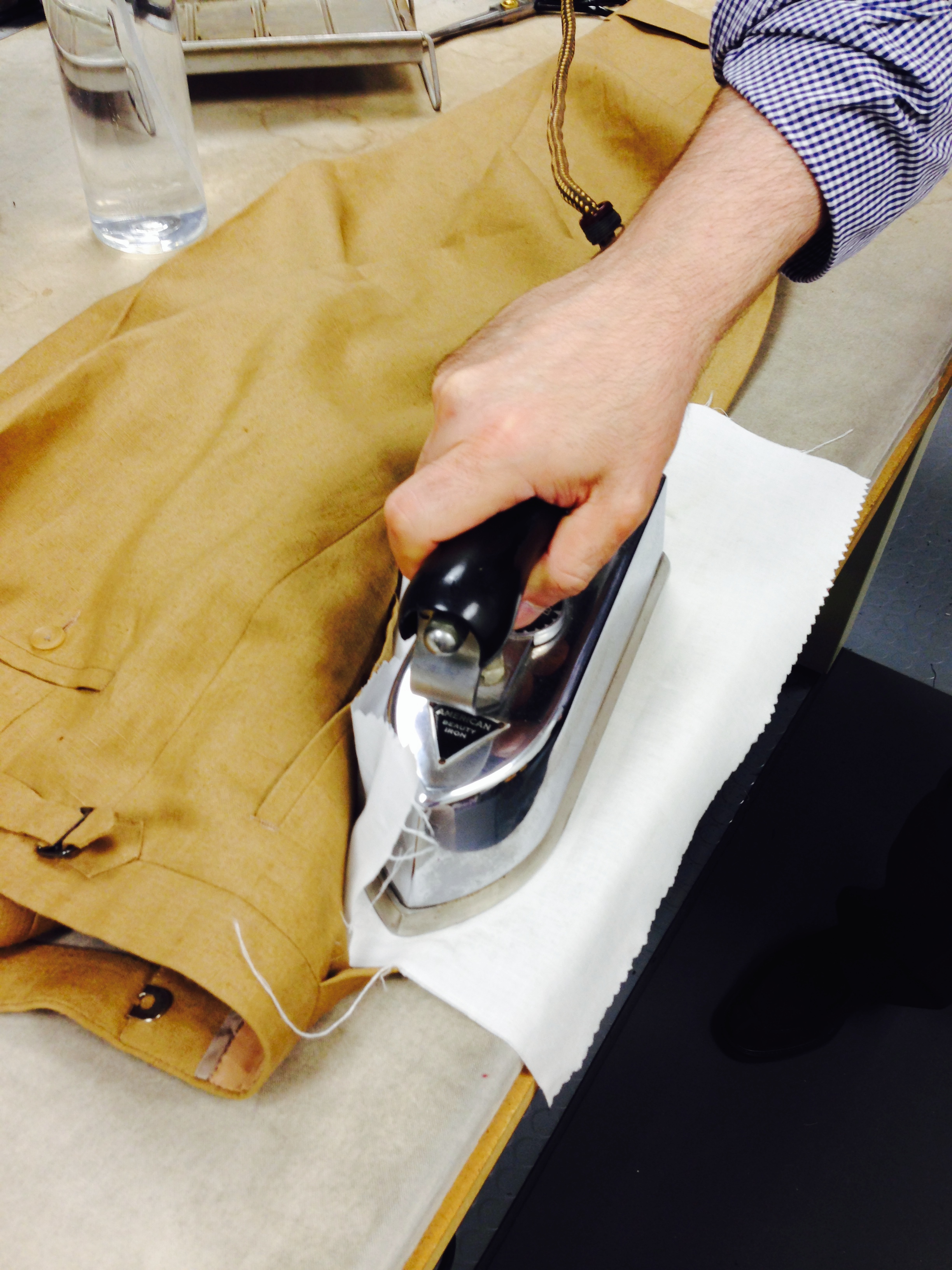

Rolling or permitting the excess length to stack are both acceptable according to current fashion, and purists would tell you that jeans were never intended to be hemmed. Personally I find the former slightly too noticeable and the latter impossibly uncomfortable. Both are also loaded with style and cultural connotation and one or the other can be distracting depending on context. For these reasons I hem, but only after I am certain the jeans have settled into a consistent length size. Make certain to specify an original hem; this procedure will ensure the finished hem will resemble the authentic, crinkled, half-inch jeans stitch.

This is the point in the essay where denim purists send me enraged letters for having skirted the technical aspects of buying, breaking-in, cleaning and living with raw denim jeans. Keep in mind, though, that these are the same people who freeze their pants. I like jeans, and I think those made of raw denim are the best choice. But I also firmly believe that they are casual pants made for leisure and the instant they require much more energy than, say, a dress shirt, they lose my interest. Here is how I do it.

Buy raw jeans, removing all labels, including interior logos and size tags

Soak flat in bathtub filled with lukewarm water

Hang to dry in crisp, autumnal breeze

Endure wearing on several occasions around the house or garden

Ignore the fact that they are likely far too long until they have softened

Take to alterations tailor to hem, specifying “original hem”

Wear often, launder infrequently on cold, gentle cycle, hang-dry