Lost in (Closet) Space

And to think: this built-in once held some very questionable pajamas in Barney's haberdashery department.

Of the tropes employed by those house-hunting shows that clog cable in the evening, the most tiresome must surely be the one in which the wife complains to the husband about a lack of closet space in some prospective home and the husband, who inevitably likes the house because of the finished basement, turns to the camera, eyes rolling, and mumbles something about too many shoes anyway... There are several things wrong with this. To begin, as long as they are worn, there is no such thing as too many shoes. Also, finished basements are always drafty and acoustically poor no matter how many neon beer signs are installed. A cobwebbed wine cellar would be much better.

The biggest problem though is that these dim souls never think to suggest the solution to the problem: furniture. Perhaps they are unaware that an entire sub-genre exists dedicated to the storage of clothing. They might mollify their wives with a wink and a promise to find a grand old armoire. Or a flame-mahogany chest of drawers. A silk-lined lingerie tower? A brass-inlaid steamer trunk? I could go on, but I think the point is sufficiently made: closets aren’t the only players in storage.

Of course this is heresy for most people. In fact, closets are so important to real-estate agents, they’ve added the word “space” to the end. Grammatically, this is unnecessary; existentially, the closet (a small room with some shelves) has been elevated to the status of deal-breaker/maker. Good for closets, perhaps, but bad for style generally.

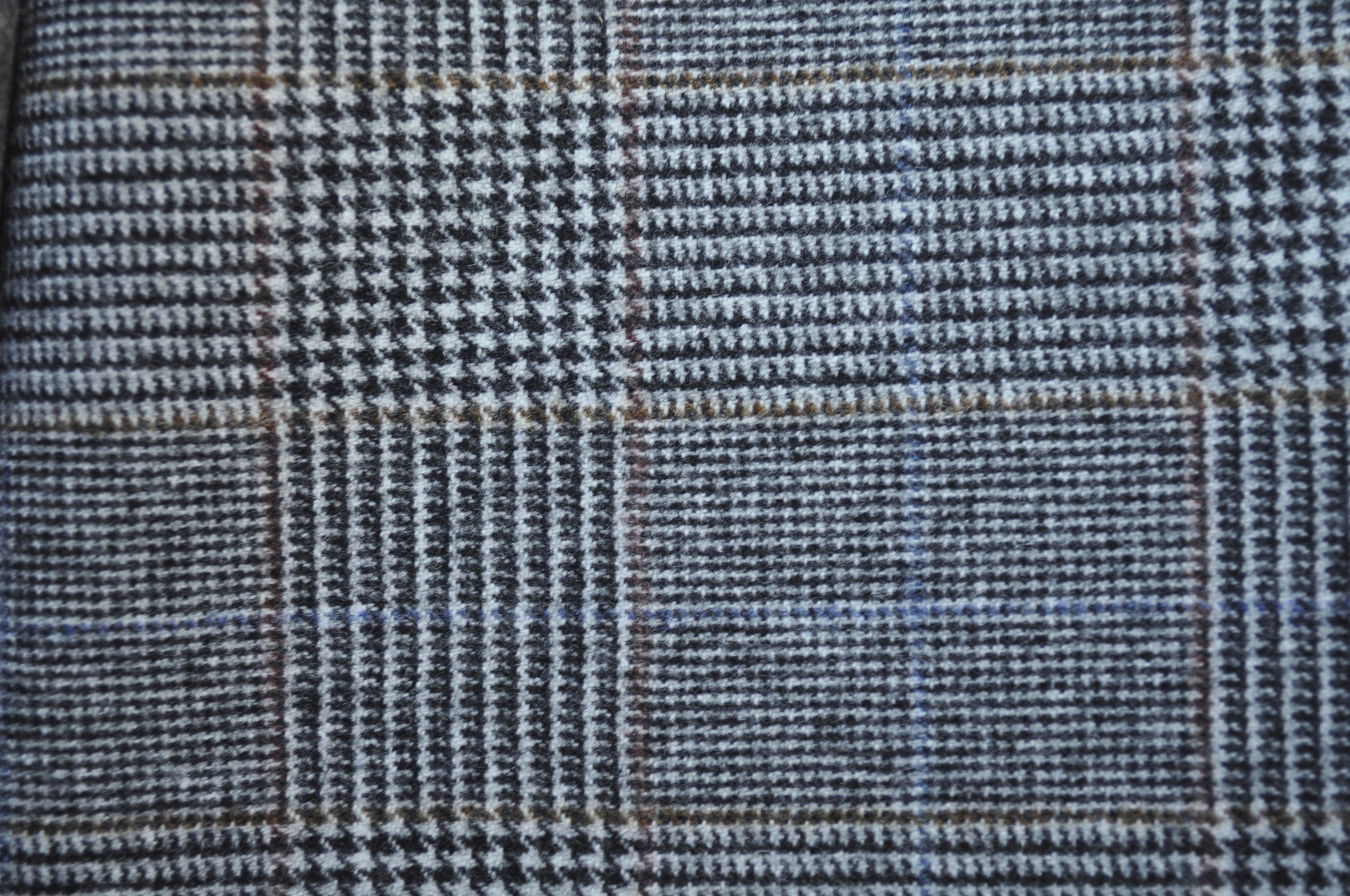

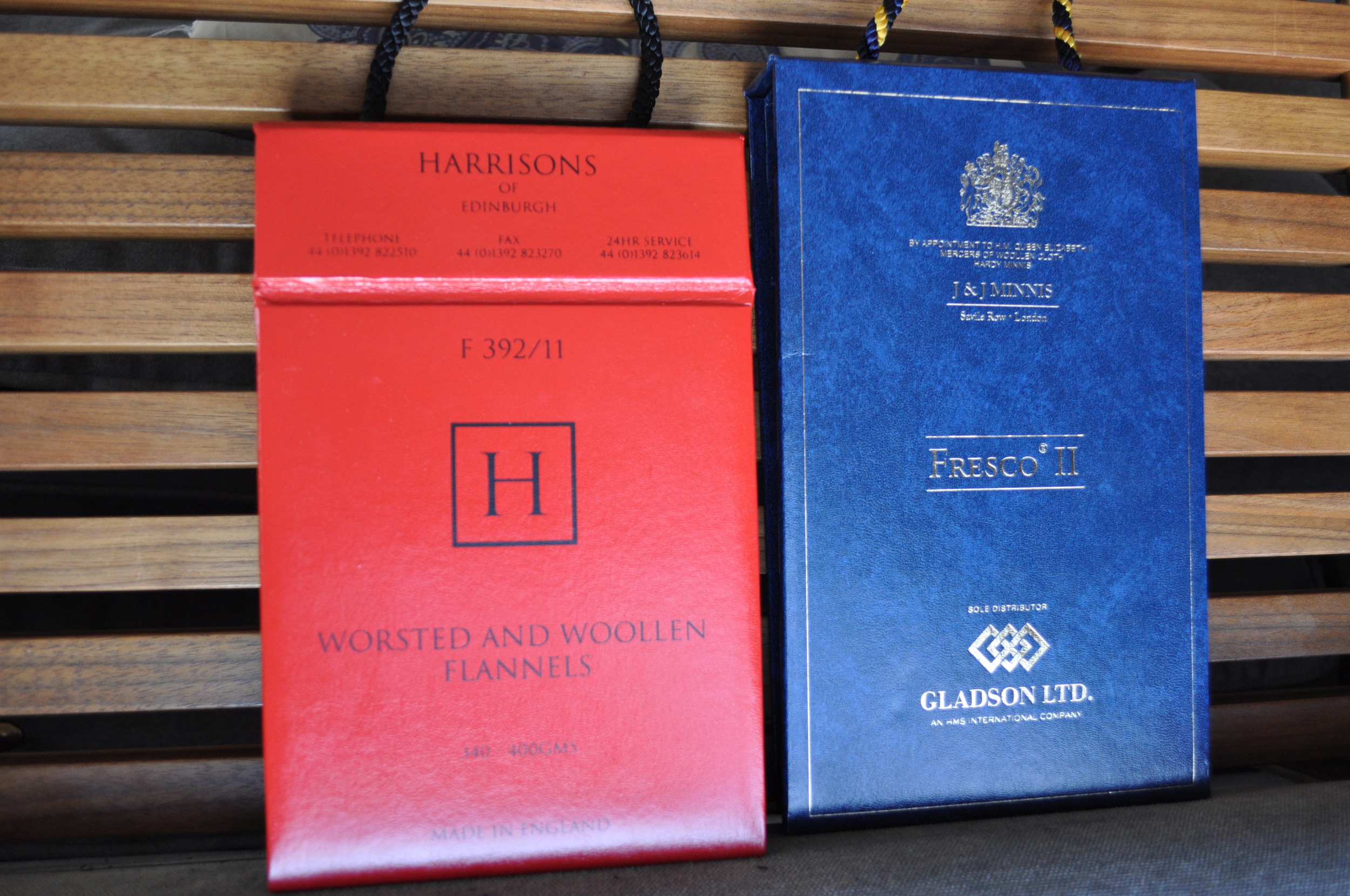

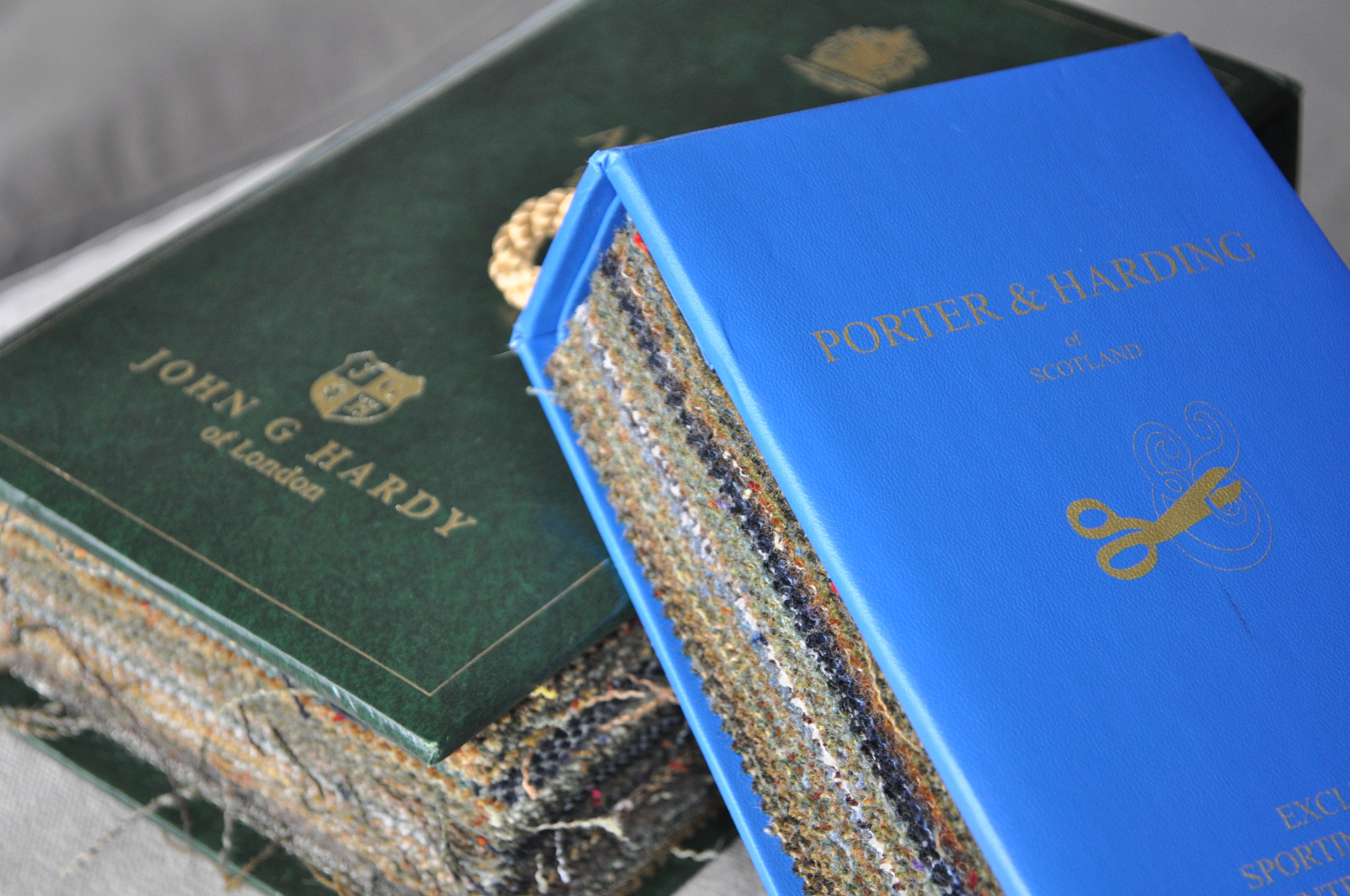

Surely the root of the issue is that we have too much. This is a problem hardly limited to clothes; unwearable things have a nasty habit of loitering in closets. But if we focus for a moment on the wearable stuff, I think we generally find plenty of fat too. I will avoid any prescriptions of how many of what one should have if one is a traveling salesman versus a downtown lawyer. Most are aware of their needs. I am, however, a firm proponent of the practical wardrobe. Not monastic austerity--just honest editing. The real demons of practical wardrobes are those garments we regard with potential, or, worse, sentimentality. Garments that possess a vague sense of importance and little else. And it is closets--no, closet space-- that encourages the gathering of all this unwelcome debris.

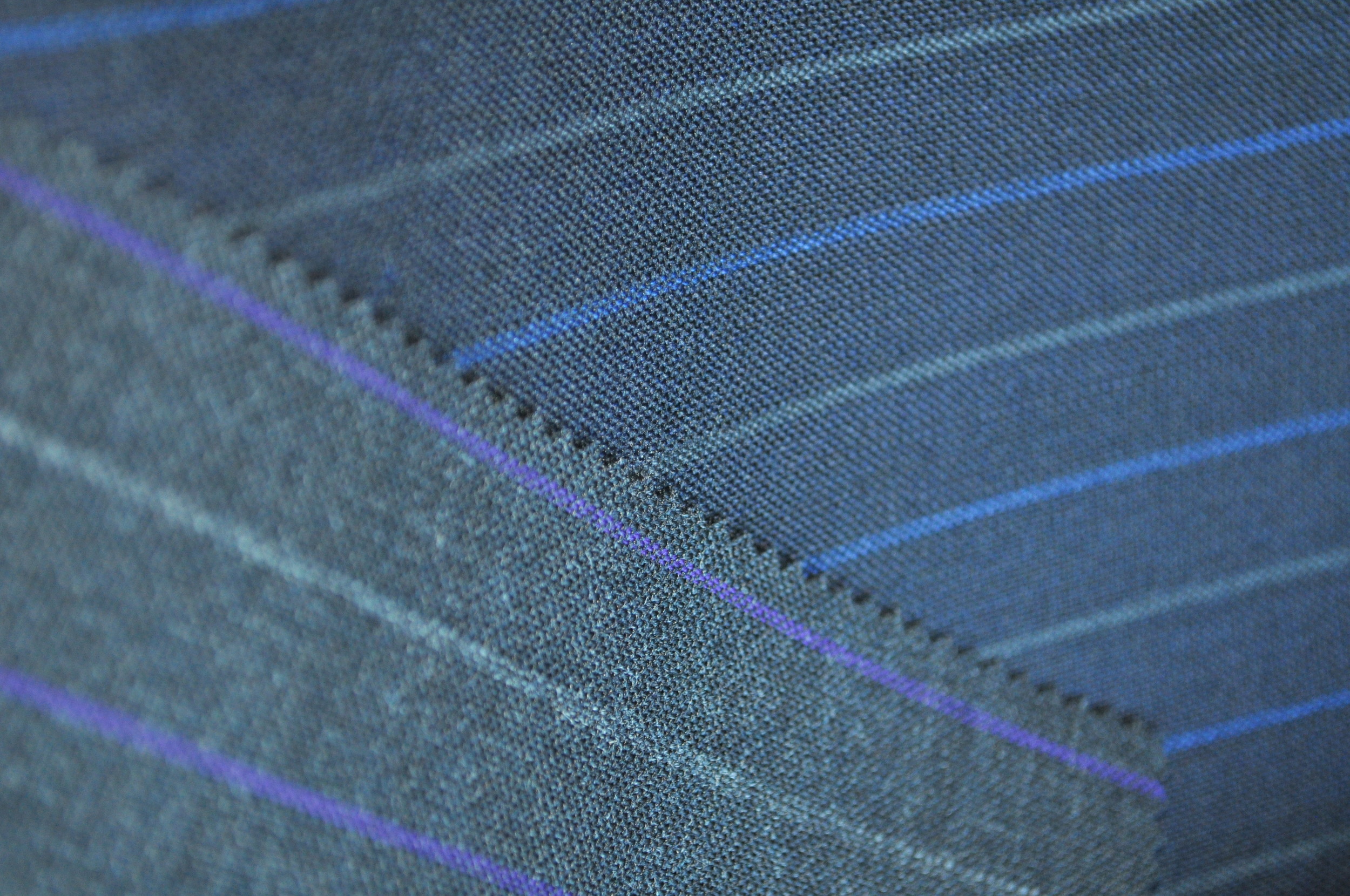

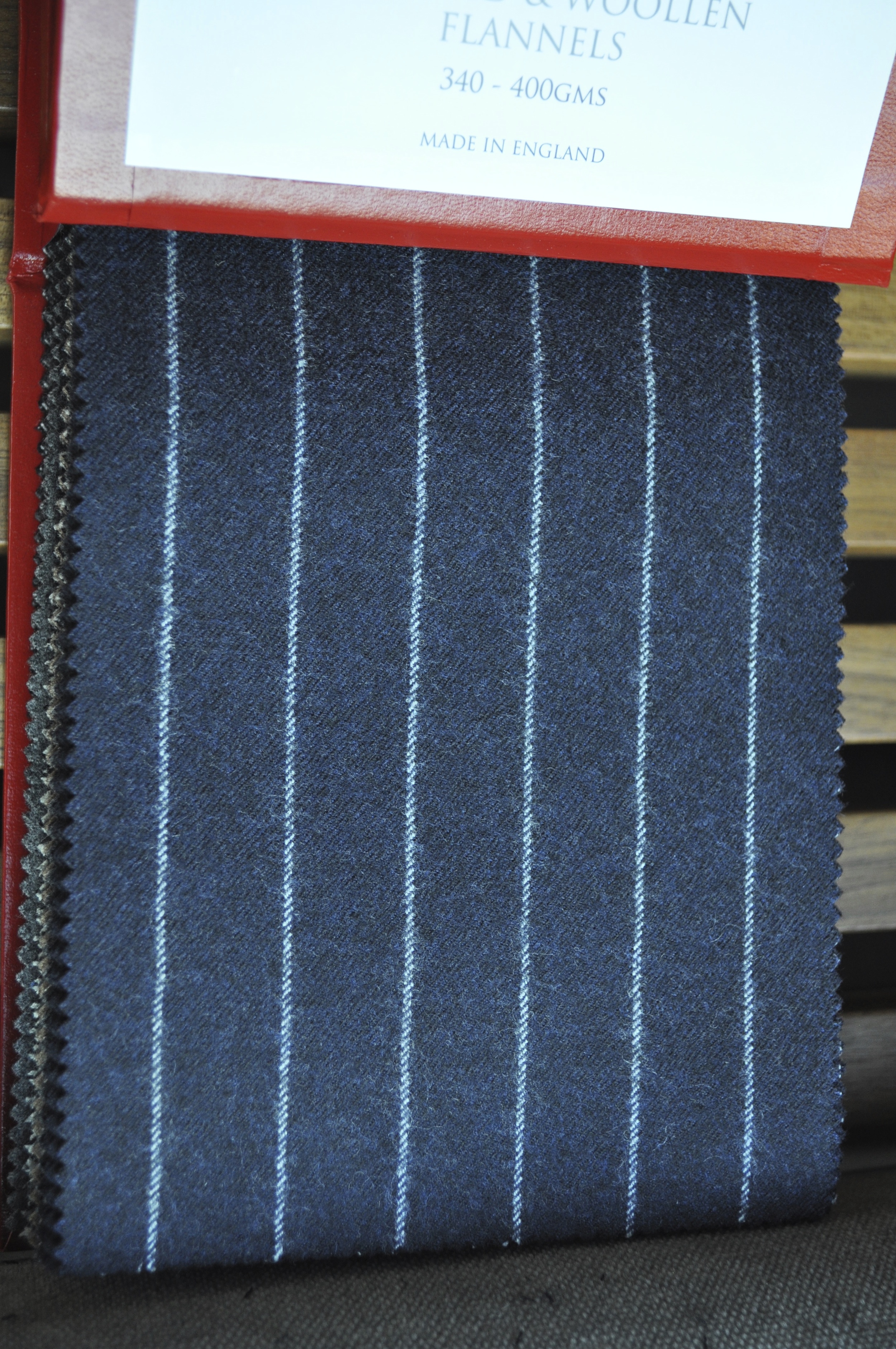

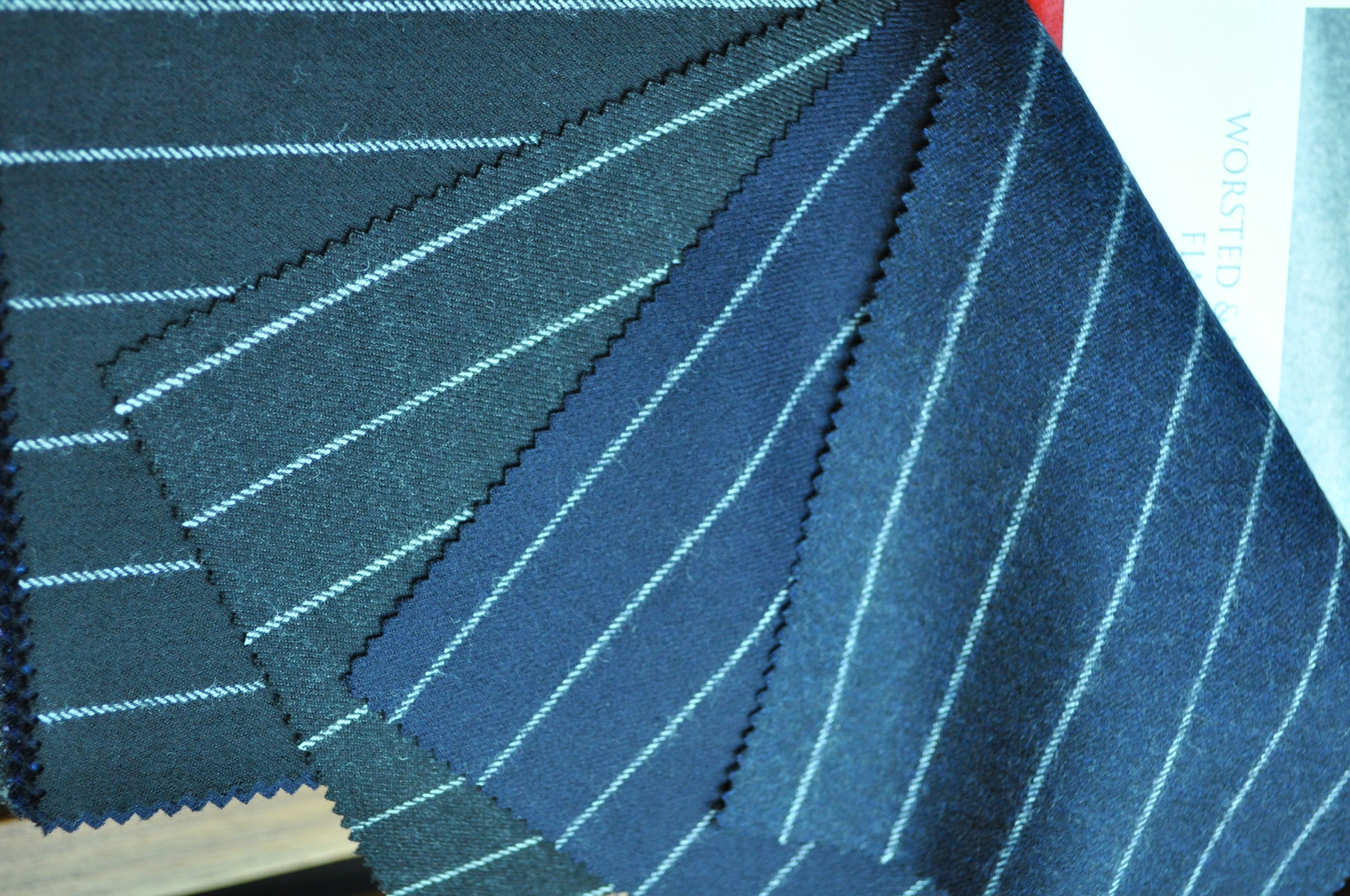

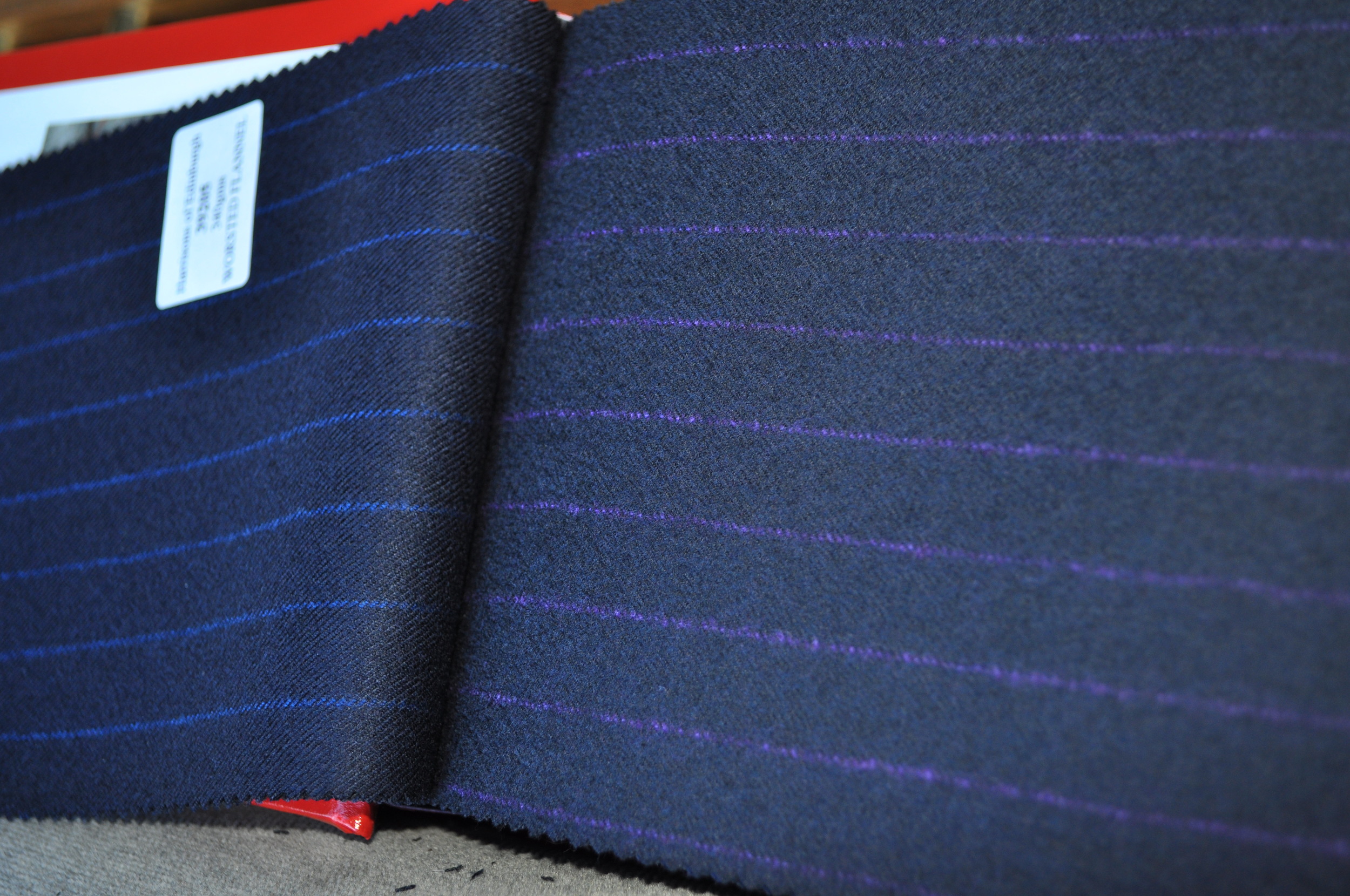

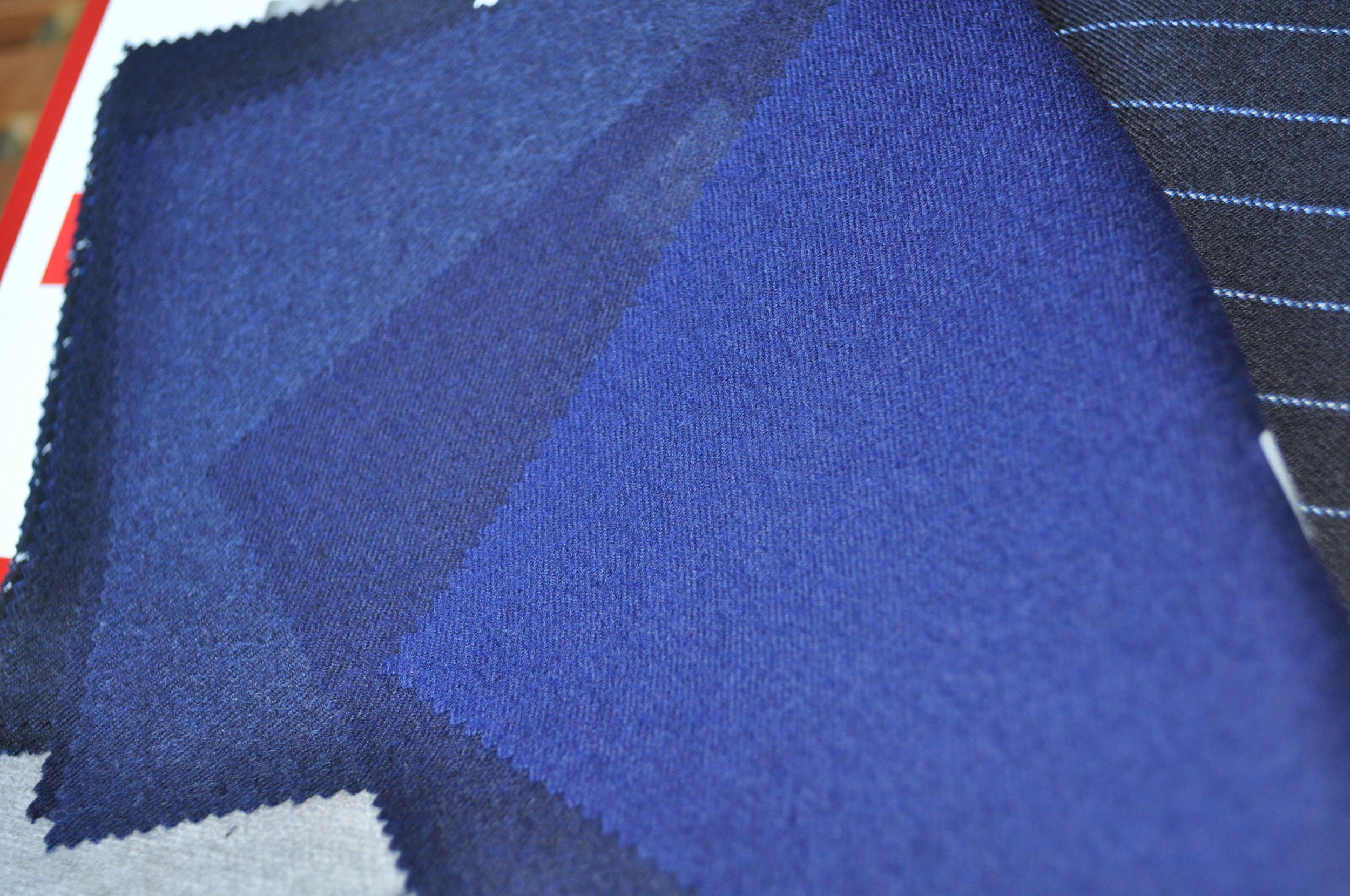

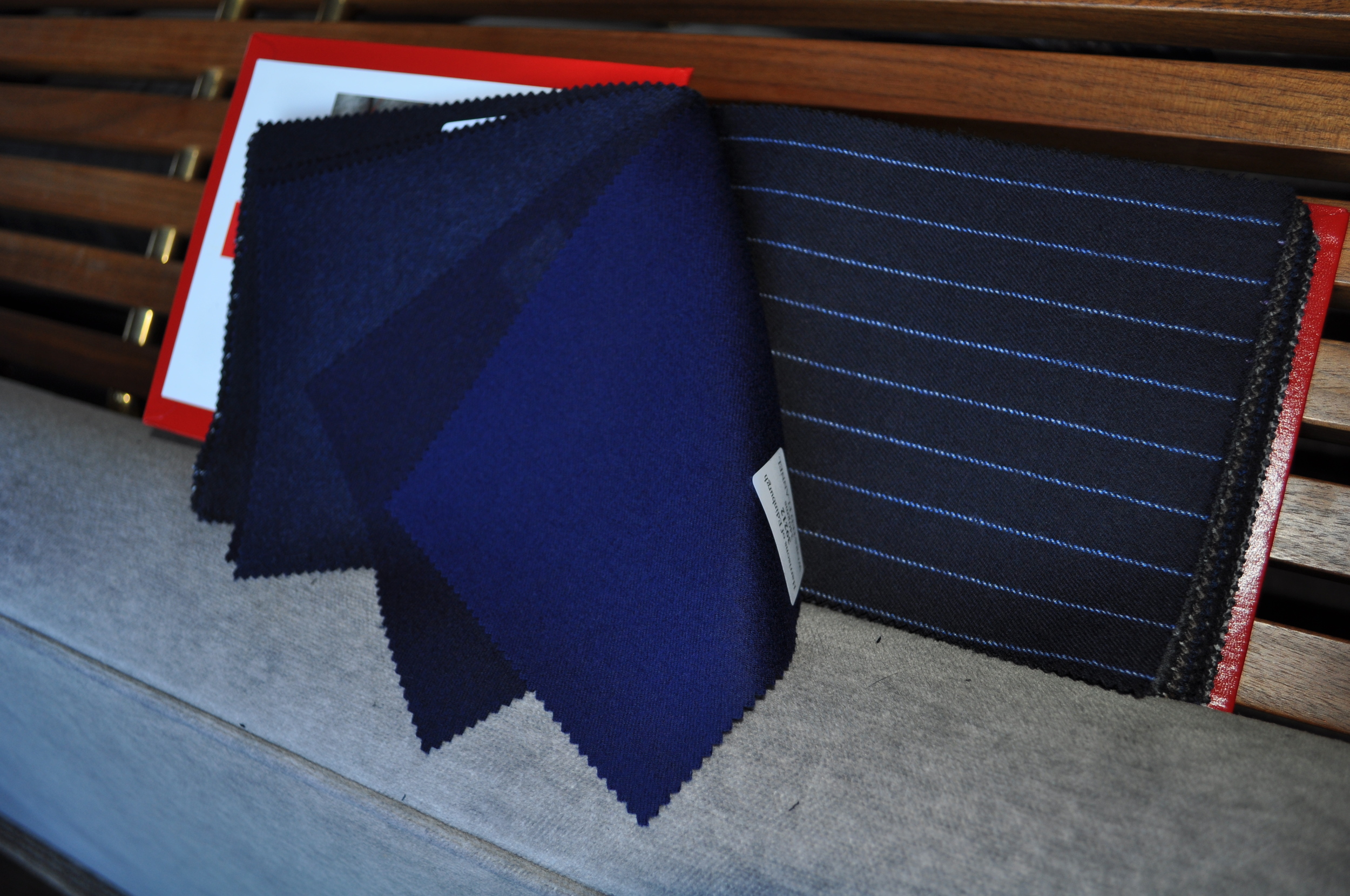

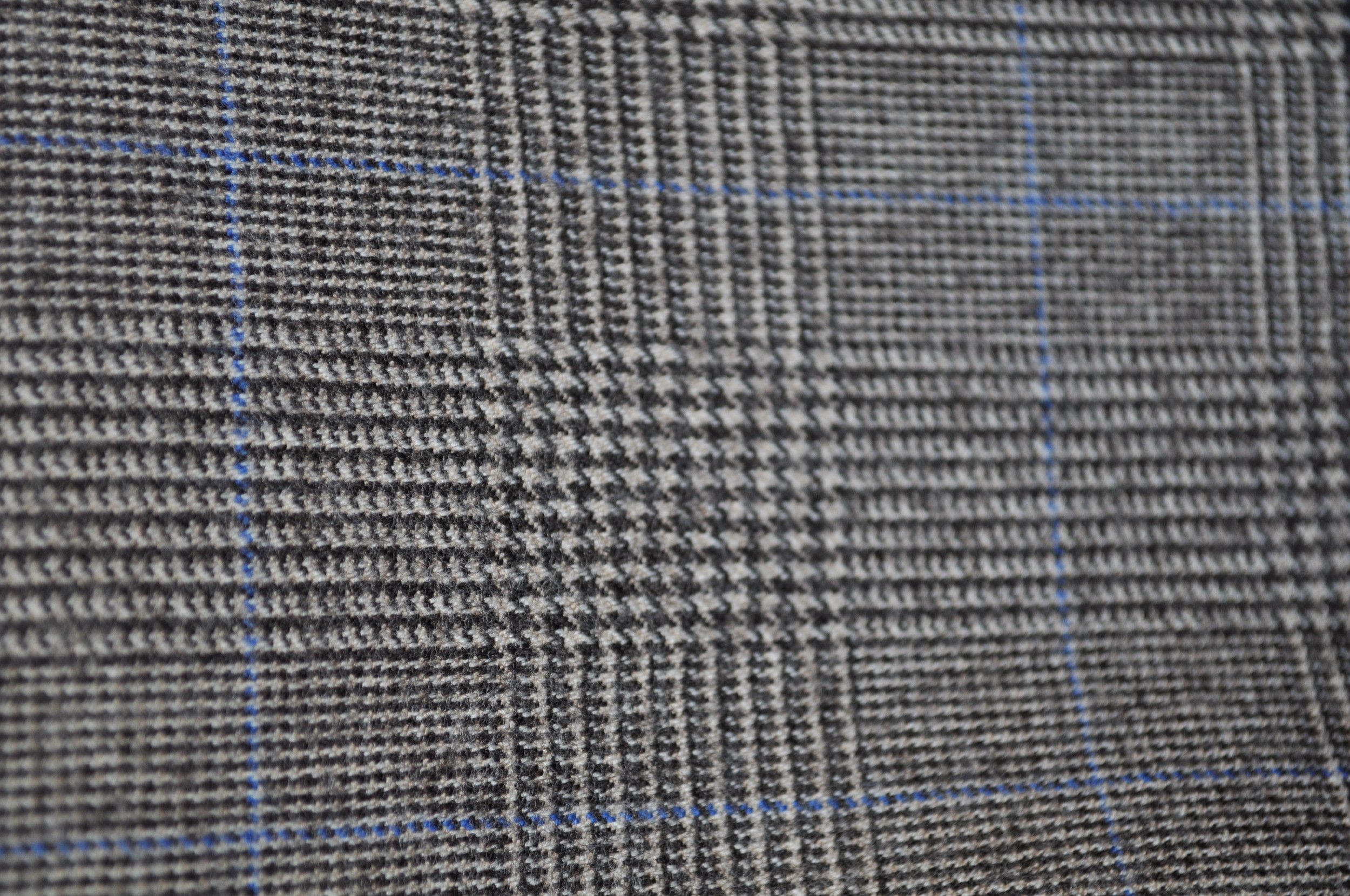

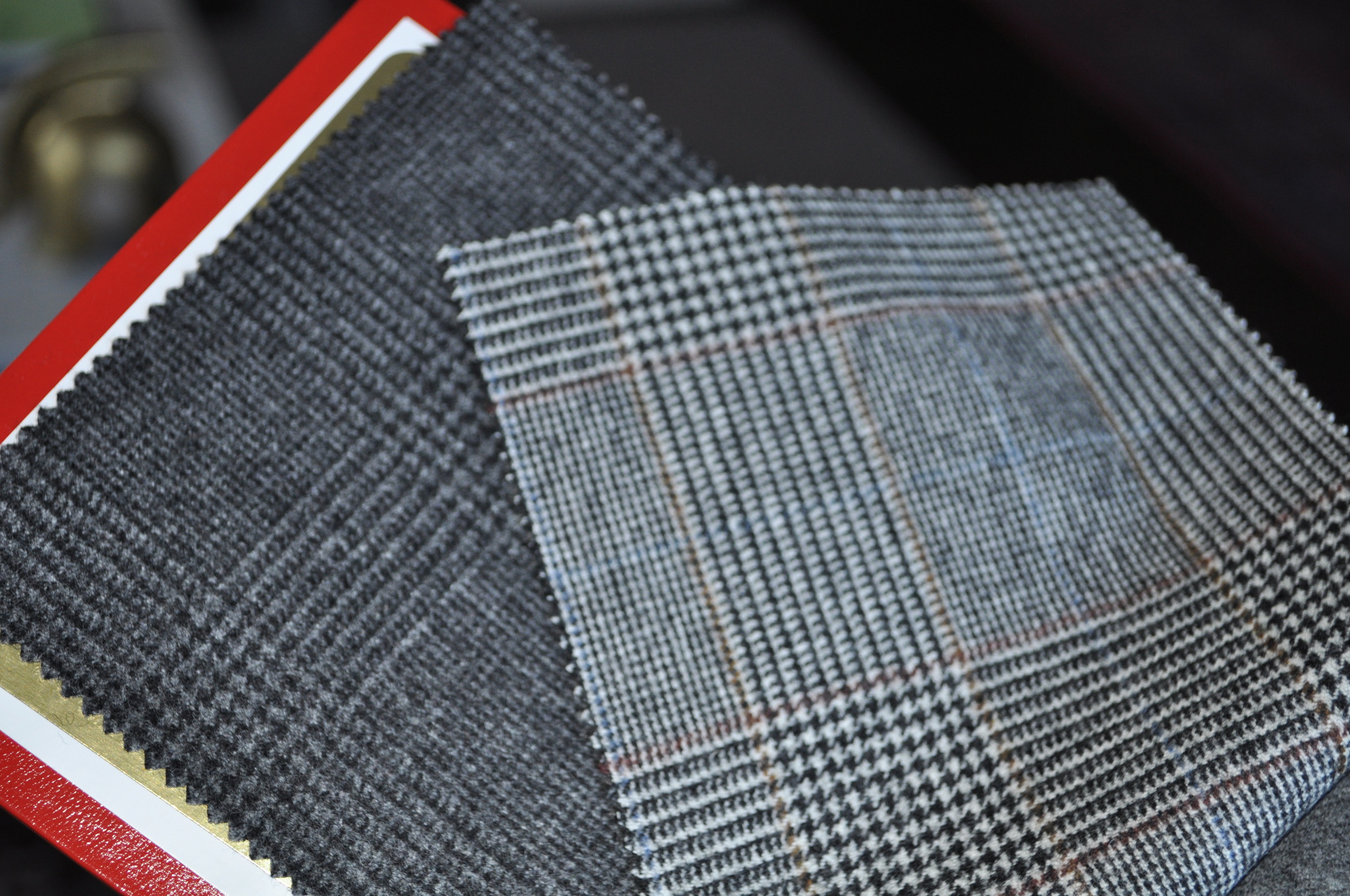

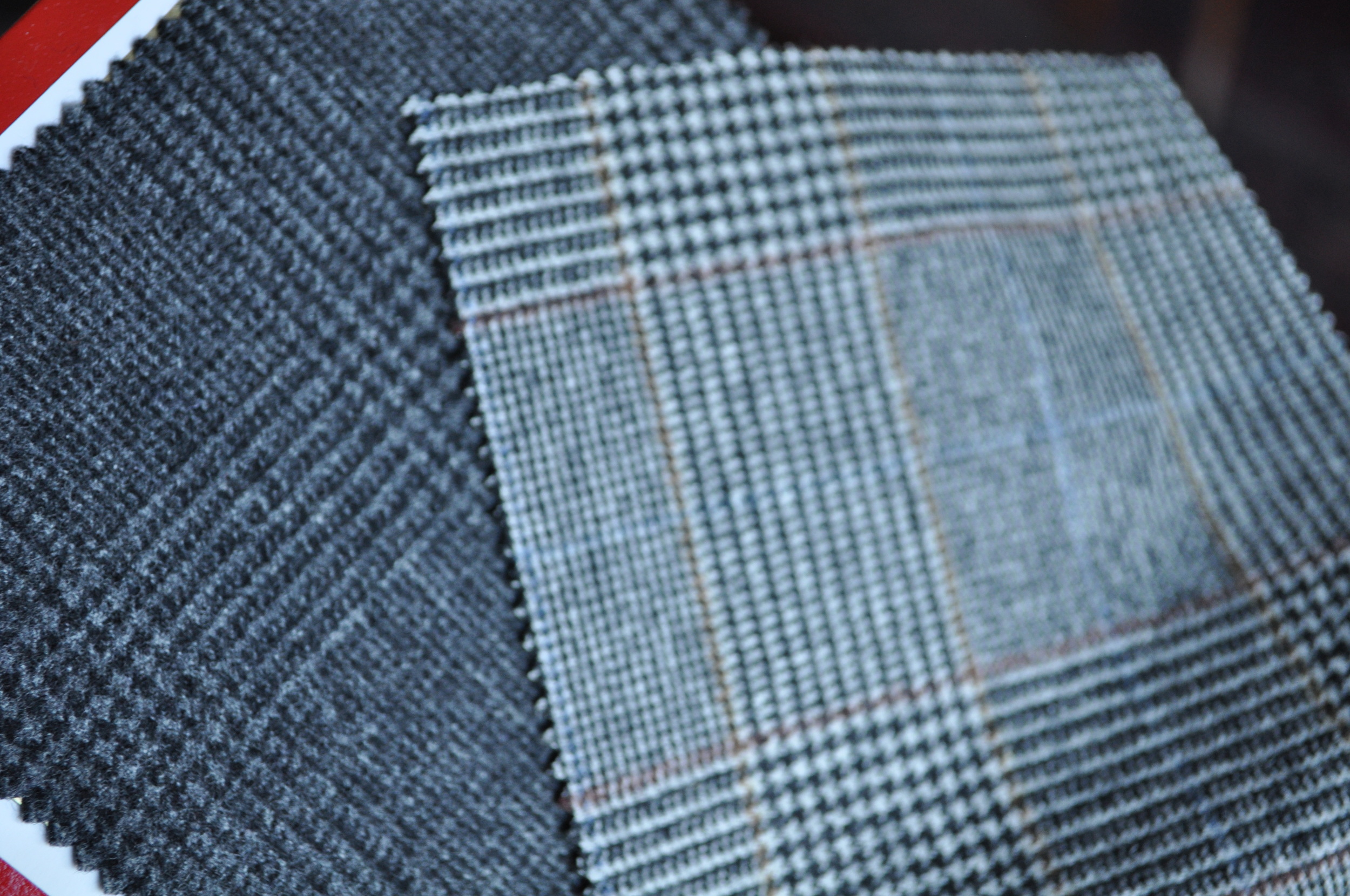

But what does this all have to do with style? The answer is twofold. One, dressing isn’t always an easy task. Perhaps one is in a hurry, or attending some social function where clothes must be more carefully selected than usual. It has always seemed to me that too great a variety is perilous in these scenarios. When the variables are reduced and well organized, dressing under duress is considerably easier. The second answer is perhaps more romantic: a beautiful armoire neatly hung with well-fitting suits can be a magnificent thing. The same may be said of a sturdy bow-front chest containing carefully folded shirts and sweaters. Or a brass rack with well polished shoes, each more gem-like than the last.

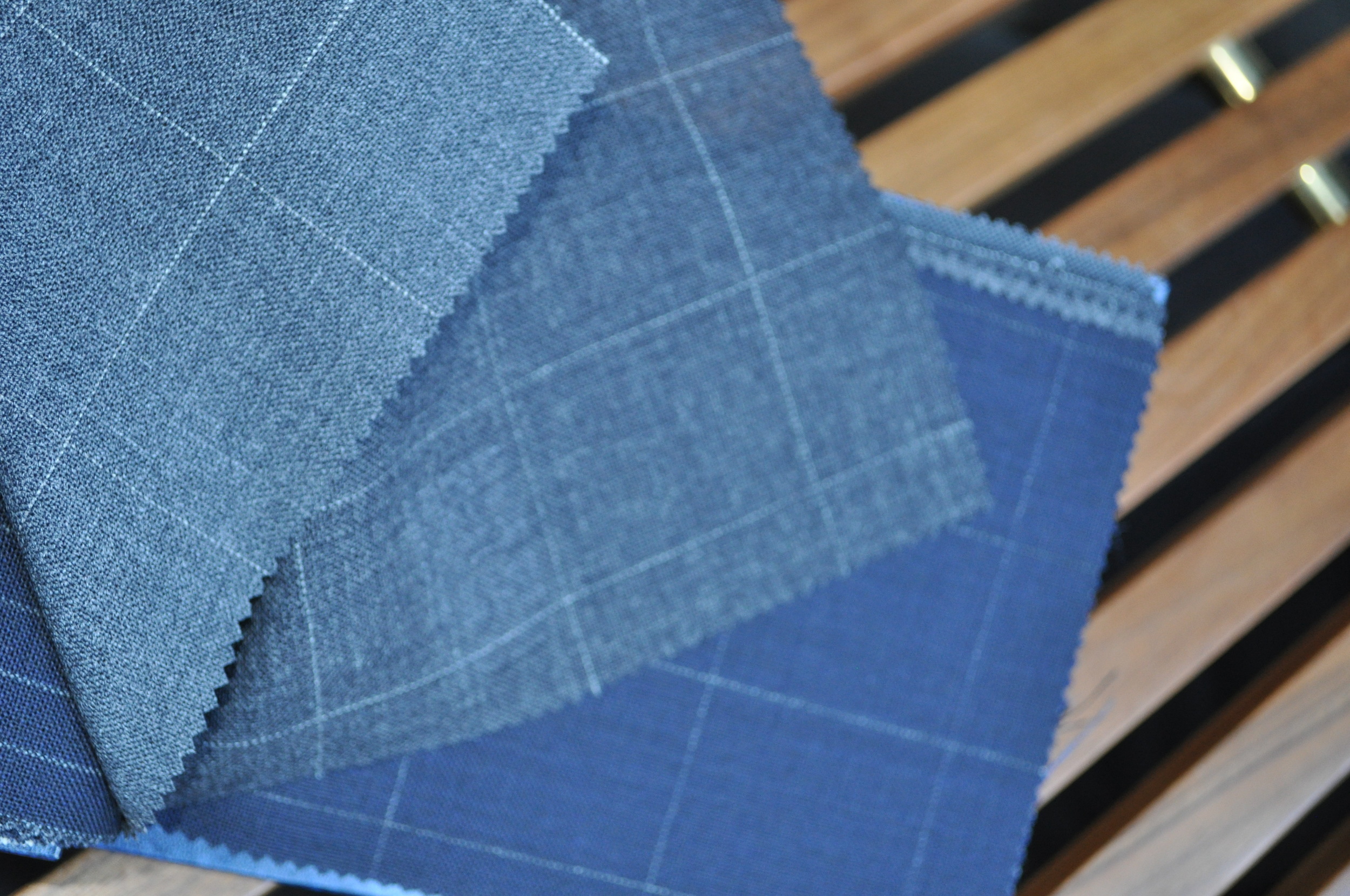

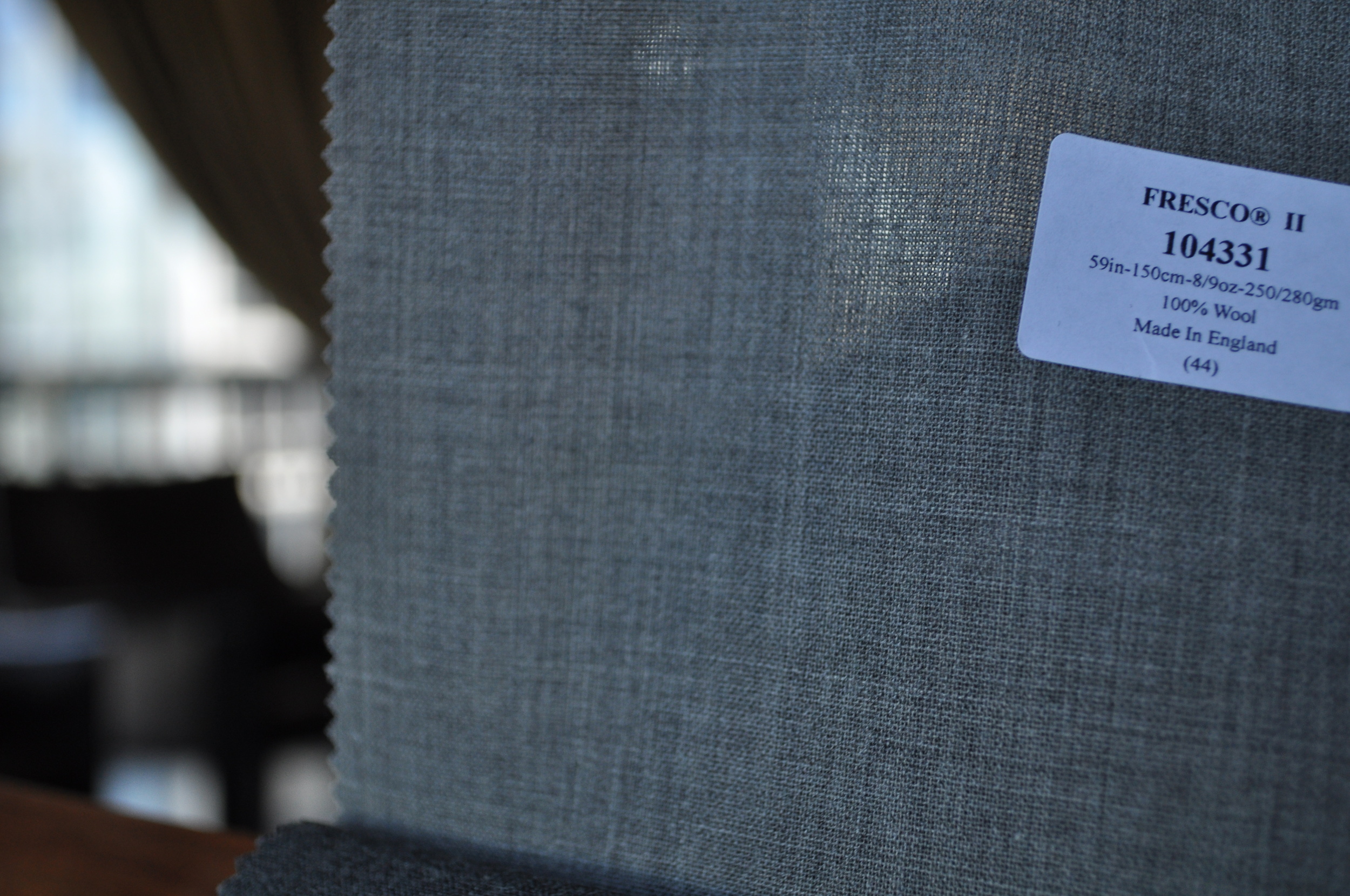

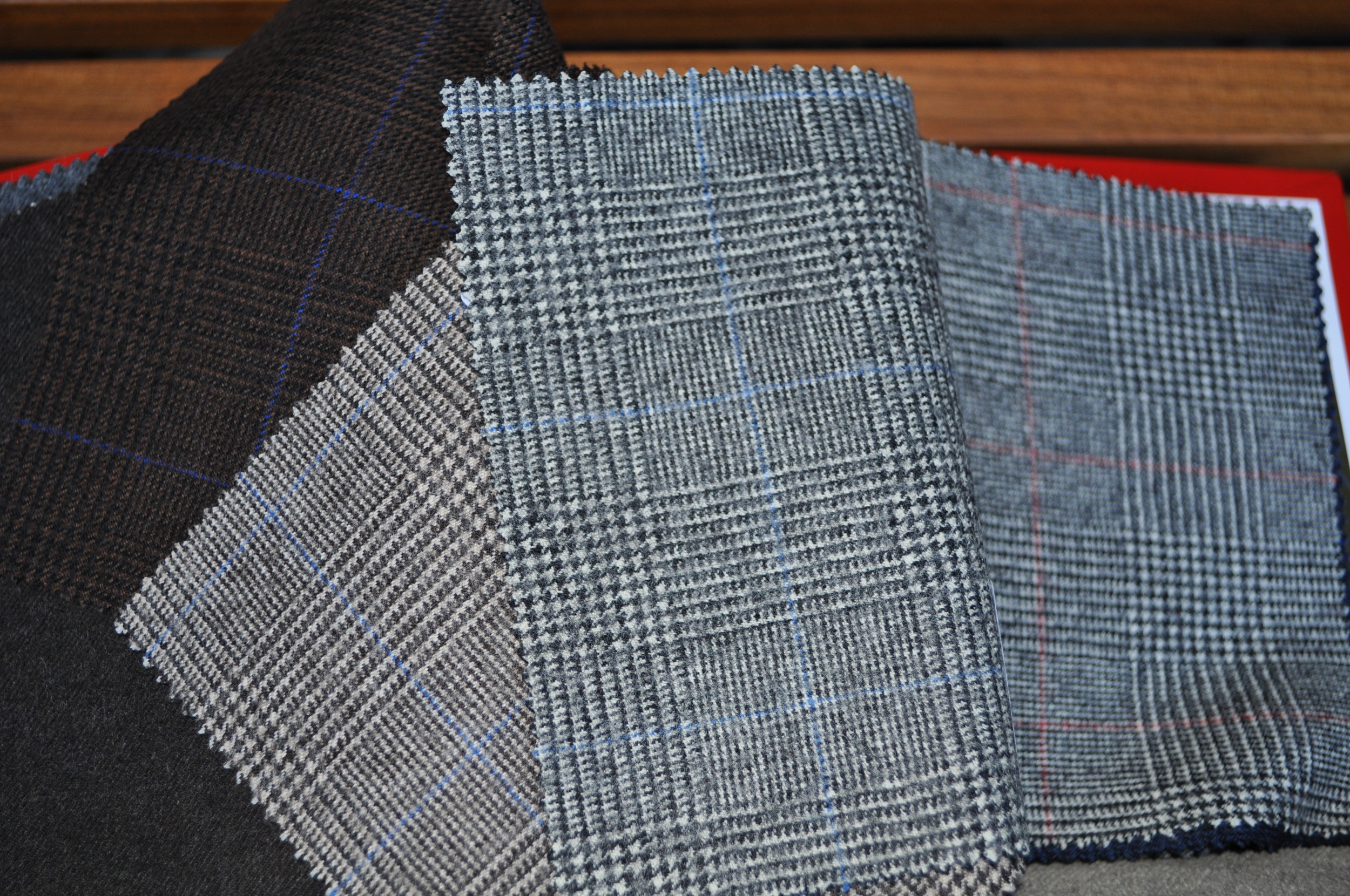

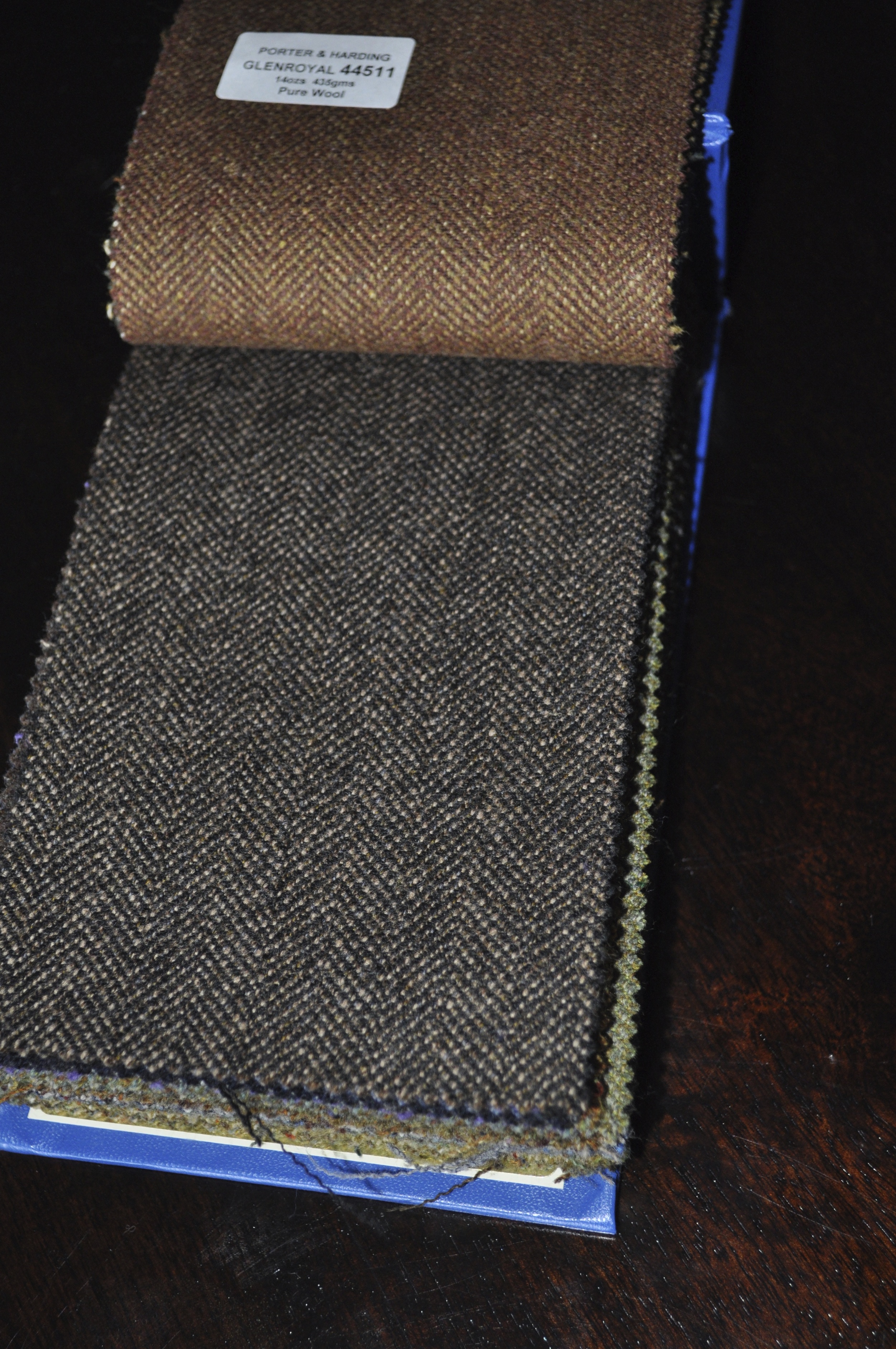

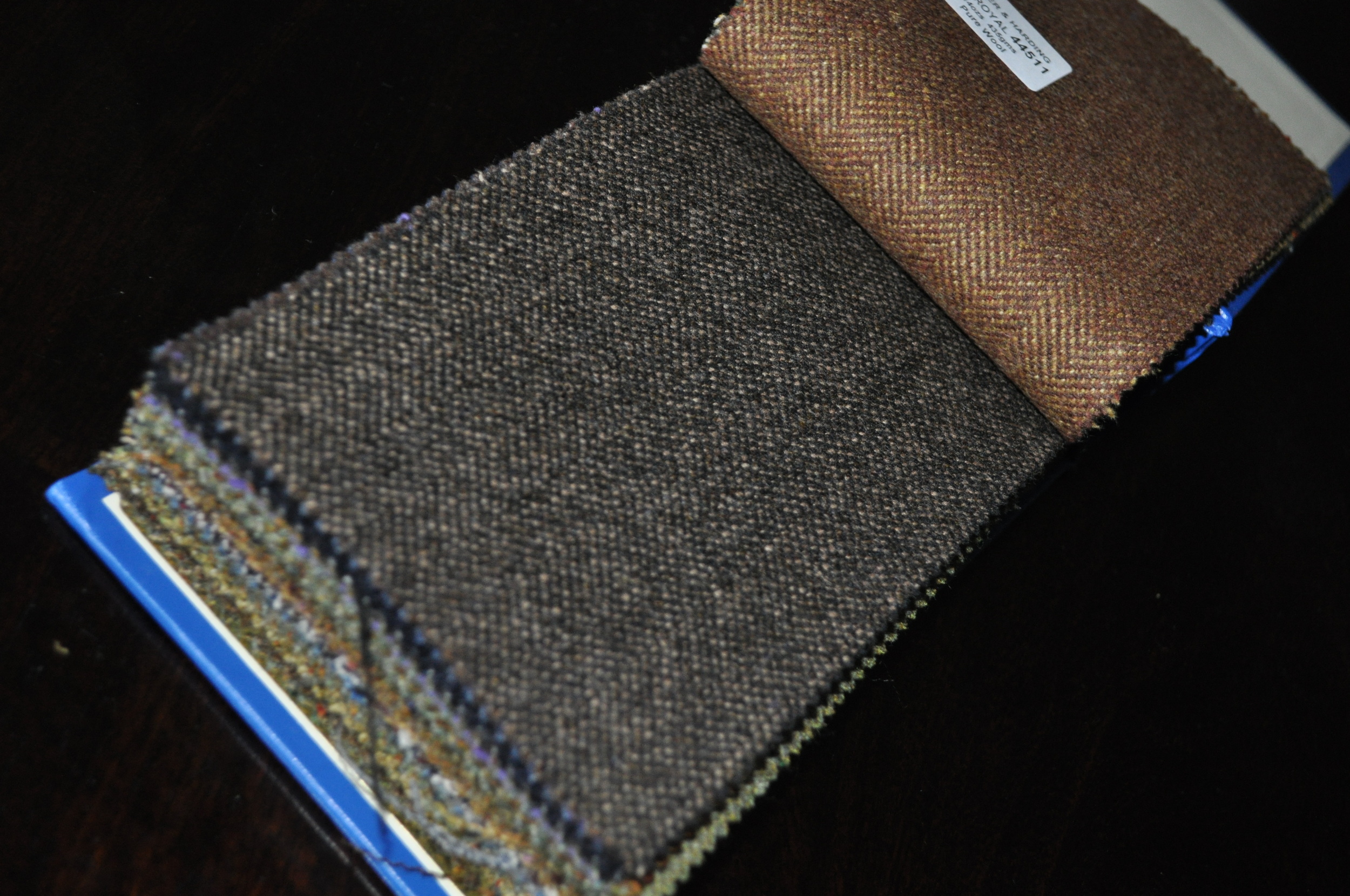

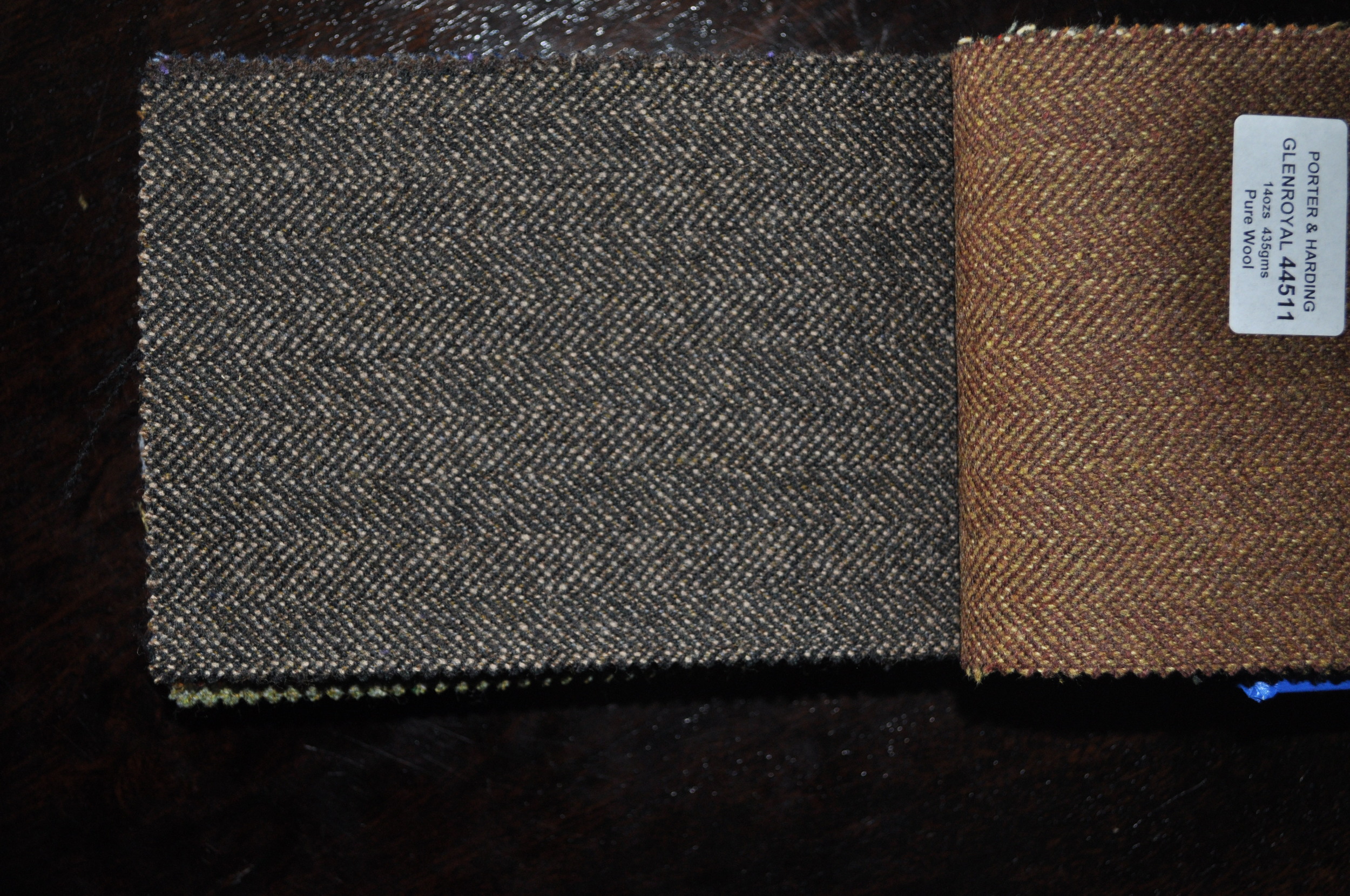

My contribution is more modest. Some years ago when the Barney’s around the corner was moving, they decided to sell the shop’s fixtures and furniture. Using a crow bar and a hand-saw, I liberated a display unit from the haberdashery department. After considerable wedging, sanding and painting I have a very satisfying place to hang suits. The drawers hold socks, and the cupboard luggage. The surface beneath the suits has indentations where I stack handkerchiefs and gloves and there’s a spot for brushes and shoehorns. The best feature though is its size--large enough for my needs, but too small for anything extraneous. Closet space can go boil an egg.

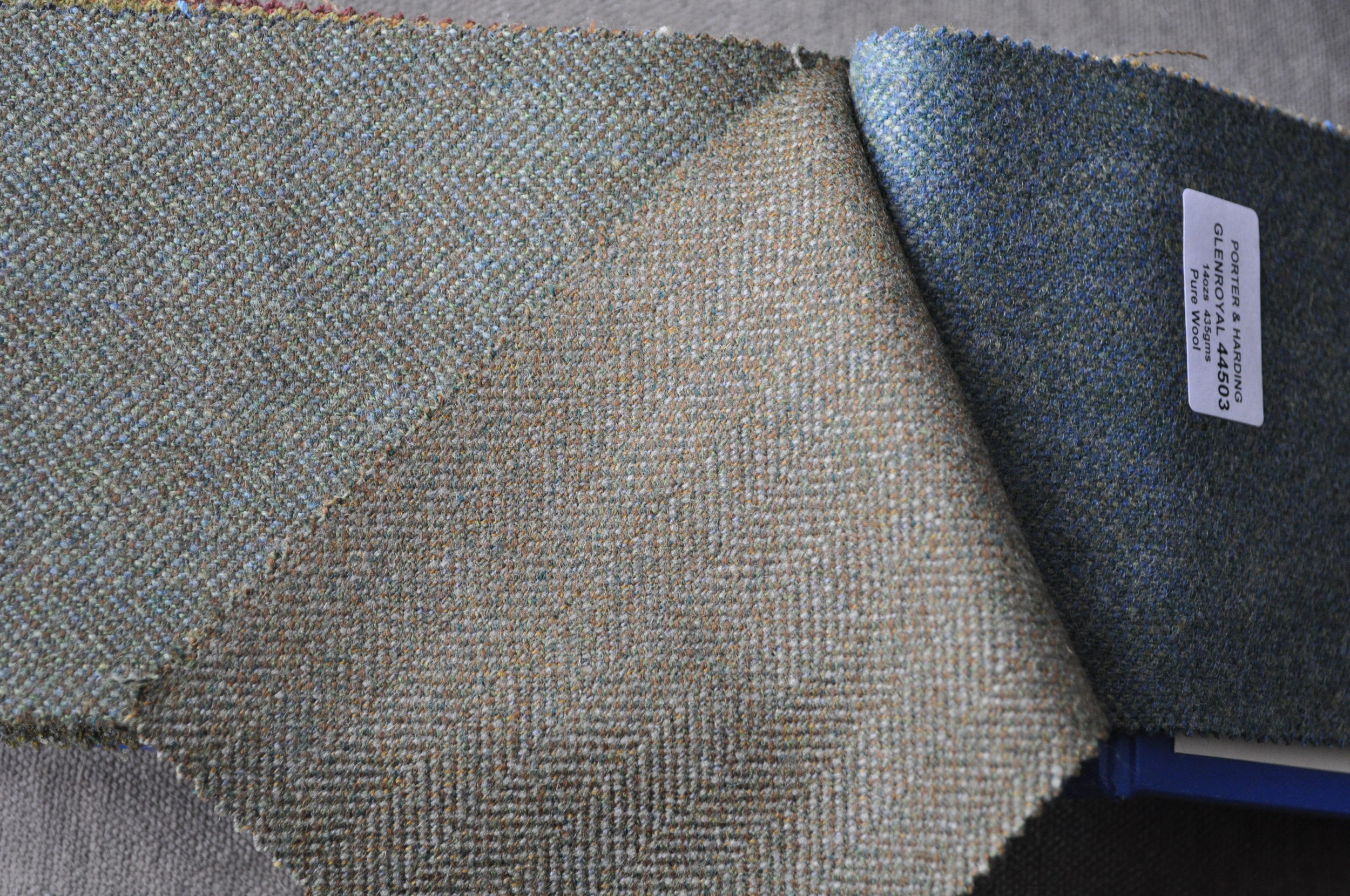

Deep space: 10,000 light years from anything remotely elegant.